Column: Sprinter Tianna Bartoletta wants people to ‘give a damn’ about the fight for Black equality

- Share via

It should be simple. Plot a route and a pace, start running, and wait for the endorphins to kick in. Tianna Bartoletta’s reality is more complicated than that.

When she leaves her Bay Area home for a training run she knows that people she encounters might not see a three-time Olympic gold medalist, a driven athlete who ran the first leg of a world-record performance by the U.S. women’s 400-meter relay at the 2012 London Games, started the relay off toward gold again four years later, when she won the gold medal in the long jump at Rio with a personal-best leap. They might see only a Black woman running and decide she’s an interloper in their neighborhood, in their world, and who knows what they might do next?

She decided she’d set the tone and take the initiative “when approaching someone who doesn’t look like me or have the same complexion.” So she follows a three-step protocol: She smiles, raises her hand in a friendly wave and then says something cheerful about the weather or the day before continuing, hoping that was enough to earn her safe passage home.

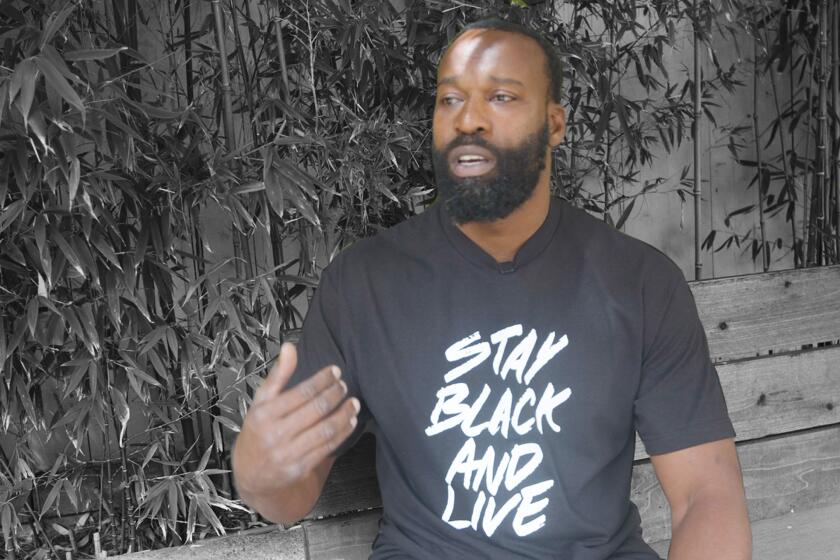

During a protest outside SoFi Stadium, Hall of Fame wide receiver Terrell Owens demands NFL commissioner Roger Goodell apologize to Colin Kaepernick.

“It’s not something I was ever taught to do, yet it was inherent, it was just an intuitive reaction I had to approaching people. It felt like it was just programmed and ingrained in my body,” she said during a phone conversation.

“I have had so far no negative reactions, and honestly I don’t set myself up for those because I’m modifying my behavior before I even reach any other person, if that makes sense. There isn’t even a situation where I’d want to know what would happen if I don’t do that.”

It’s heartbreaking that an Olympic and world champion who has been cheered by thousands on global stages feels she must make it clear she’s not threatening when she runs past people on the street. “Sure, it’s awful and I shouldn’t have to do it,” she said, “but you want to survive.”

Bartoletta, 34, has never run away from anything. She continues to push up hills and down streets while she recalibrates her life and athletic schedule after the postponement of the Summer Olympics, putting on hold her planned return to the molecular microbiology program at the University of Tennessee.

“I had to basically do a cognitive shift. It’s not happening this year, but as far as we know it is happening next year,” she said of the Tokyo Games. “I could choose to look at it as a delay that is horrible and devastating because the delay comes with its own issues, of contracts and sponsors and all that, or I could look at it as I have another year to prepare to defend my title. And there’s no real world in which having an extra year to prepare for something is bad.”

Working on her blog is cathartic, helping her process the trauma of undergoing emergency fibroid surgery last December, the Olympic delay, and the gnawing anxiety she has felt since the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer triggered nationwide protests over institutional racism. She’s a keen observer with a blunt, affecting style. Writing is among her ambitions, and she has already found a strong voice.

“I don’t know what more to do, than what I’m doing to show and prove that my life has value,” she recently wrote. “But does it really matter that I think it does? When I have zero confidence that there would be any consequence if someone did harm me. … In my skin, I don’t hear the clinking of my gold medals, they aren’t badges of my value, or shields from racism.”

After George Floyd’s death, former NBA player Baron Davis says people are frustrated at the lack of progress they’re seeing in fighting racial injustice.

The day she completed her first mile run — as a sprinter, she doesn’t train distances — she came home and saw the video that led authorities to arrest two men for killing jogger Ahmaud Arbery in Glynn County, Ga., three months after Arbery died. “It really shook me,” Bartoletta said. In her blog she wrote, “I went from excitement about getting back out there another day to try to lower my mile time to feeling dejected that my skin color gives me permission to do nothing and others permission to hurt me.”

Hollow promises and platitudes about injustice have become stale. During a conference call last week among USA Track and Field athletes and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, athletes criticized the USOPC’s hypocrisy in tweeting that it “stands with those who demand equality and equal treatment” after the organization reprimanded hammer thrower Gwen Berry and put her on probation for raising a fist on the medal stand at the Pan Am Games last year. It similarly penalized fencer Race Imboden for kneeling on the medal stand. “We were able to communicate emotionally but calmly to say why this was such an important issue for us,” Bartoletta said.

The International Olympic Committee, which has banned taking a knee or raising a fist or otherwise breaking protocol at medal ceremonies, this week agreed to hear proposals from its Athletes’ Commission on how athletes “can express their support for the principles enshrined in the Olympic charter,” but didn’t promise to relax its stance against protests. Hypocrisy reigns there too. “They believe that it shouldn’t be a political arena while basically capitalizing off the commercialization of the entire ideals that they’re supposed to have,” Bartoletta said. “Hopefully we can get them back in that direction, to the ideals.”

Her own ideals remain strong. “It’s clear as day that all lives don’t matter the same. And the struggle is getting people who are unaffected by others’ lives not mattering the same to give a damn about that enough to help us get to the point where all of our lives do all actually matter. And matter the same,” she wrote in a June 1 blog post. “I don’t want to have to talk about this. Or write about this. But come on, we’ve gotta meet the moment. And this is the moment we are in.”

She has prepared for this moment since she brought home a fourth-grade progress report with an F in algebra and feared she’d be scolded by her mother, a banker. Instead, her mother delivered a life lesson. “She stopped me and said, ‘I have to tell you, this is completely unacceptable. You have to be twice as good to get the same consideration,’” Bartoletta said. “She said, ‘You’re not only Black, you’re female, so this is unacceptable. You can’t make it in this world not even average. You have to be exceptional.’ And so from that moment forward, I became an honors student, AP student, dean’s list in college.

“I will never forget that conversation. ‘You are Black. Not only are you Black, you’re female, and that’s like being behind two eight-balls. You have to be exceptional,’ and that really helped me for my mind-set today.”

Watch her. Read her words. Listen to her voice, and those of her peers, as they run toward a more equitable future.

Racism and the right of athletes to protest on the podium will be among issues addressed by U.S. Olympic leaders.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.