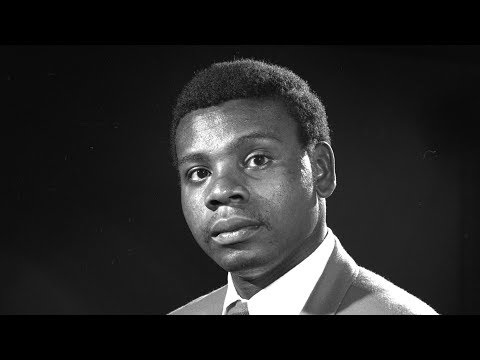

Column: The Rec Room: Perry Wallace Jr.’s resolve against racism is a story worth reading

Perry Wallace was the first black basketball player in the SEC.

- Share via

When Perry Wallace Jr. was deciding whether to accept a basketball scholarship from Vanderbilt University, he would often find himself sitting on a large rock in a park near his home in Nashville — praying. Wallace was a devout Christian and the Bible is peppered with analogies marrying displays of faith with the strength found in rocks; one of the more popular examples comes from Matthew 16:18, “…upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”

That last passage is particularly germane. In 1966, Wallace, having accepted the Vanderbilt offer, was about to desegregate SEC basketball. This, only a year removed from Adolph Rupp’s all-white Kentucky Wildcats squad losing to Texas Western, which featured the first all-black starting five in tournament history.

“He would tell me we can all treat each other in any of three ways,” said Andrew Maraniss, author of “Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South.” “We can treat each other well, treat each other poorly or not be treated at all.

“He said when the team was on the road, he was definitely treated poorly, but the hardest part was being in Nashville, on his own campus, and not being treated at all. On campus, he would be asked to be a superhero during the game, but away from the game he would be a nobody. He wasn’t allowed to join a fraternity. If he and other black classmates were sitting on the front row of a lecture hall, none of the white students would sit in that row or behind him. Normally in a lab, the person who sits next to you would be your lab partner ... well, no one would sit next to him.”

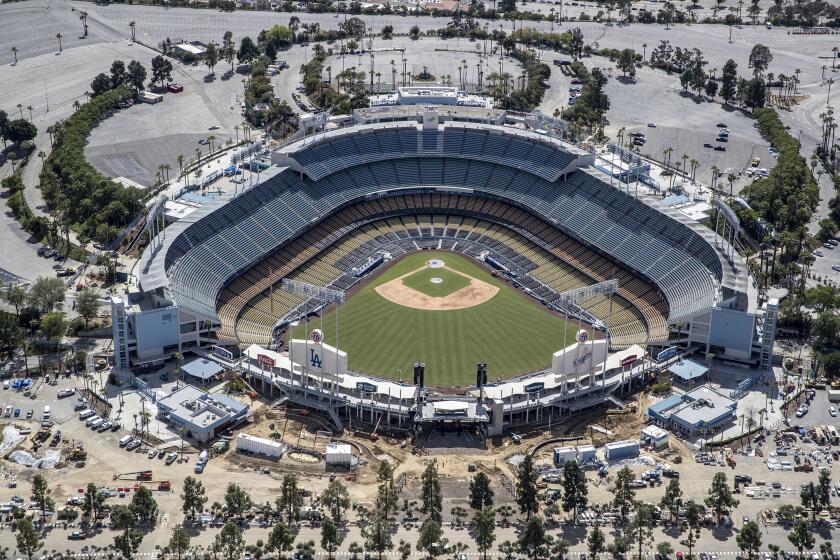

There was something missing at Dodger Stadium on a day that was suppose to be Opening day in MLB.

I became aware of Wallace’s story — he passed away in 2017 at age 69 — as I was searching for a book to kick off a virtual book club with L.A. Times readers and listeners from my 710AM ESPNLA radio show. I don’t know about you, but I can only binge classic games for so long. And unless DJ D-Nice has plans to host virtual dance parties on Instagram Live every night, I had to find a way to connect in a socially distant world. Felt like a good time to remember we all stand on the shoulders of others.

“He was the most impressive person I had ever met,” said Maraniss, whose interest in Wallace dates back to his time as a student at Vanderbilt, which he attended on a sports writing scholarship in the 1990s. “He loved learning and he really enjoyed teaching. As a white person, obviously there were things about being black I didn’t know or could fully understand, but he was always patient with me.

I thought it would be a tragedy if this man had lived and died and no one knew his story. To me it would be as if Jackie Robinson lived and died and no one knew about it.

“I was a history major and was taking an African American history class. I approached my professor and asked if I could write a paper about him for class. She said, ‘Go for it,’ and so I reached out to him to do the paper. But afterwards, I felt there was something bigger. It stayed on my mind for 17 years. I thought it would be a tragedy if this man had lived and died and no one knew his story. To me it would be as if Jackie Robinson lived and died and no one knew about it. I emailed him and asked if he remembered me and he said he did and that’s how it started. It took eight years to write the book, and I learned so much from him.”

“Strong” is a breezy read buoyed by Maraniss’ fastidious research and the raw value of Wallace’s personal stories. While it’s tempting to assume you already know the larger story — after all, racism in the South during the 1960s isn’t breaking news — I assure you the book opens new windows. How many trumpet-playing law professors who practice martial arts are you aware of? That too was a part of Wallace’s journey.

“You didn’t see many blacks on television back then other than in subservient roles,” Wallace recalled. “But guys like Chamberlain and Russell were actually getting a chance to look like real-life, dignified figures. It was so spectacular to see them out in a world where they were in the mainstream. And what we knew about the mainstream at the time was that we weren’t allowed to be in it. To see these guys have their strength and artistry respected in the larger world was huge. They were the ones you tried to be like.”

Maraniss, who still lives in Nashville, was happy to see the university go from expelling a black divinity school student for helping organize a sit-in in 1960 to being the first SEC school to offer a scholarship to a black basketball player in 1966 to requiring all incoming students to read “Strong Inside.” Last spring, Vanderbilt hired former NBA All-Star Jerry Stackhouse as its first black men’s basketball coach. True. it was only after the worst season in school history but hey, baby steps.

The beauty from “Strong Inside” is that Wallace doesn’t sanitize his story so everyone can feel good about themselves in the end. In fact, according to Maraniss, Wallace said if given the chance to do it all over again, he wouldn’t. The experience was traumatic and he had more than 80 other offers, including one from John Wooden and UCLA. According to the book, one of the main reasons why he didn’t transfer was that he didn’t want the racists to win.

NEW YORK -- In an era when posters of Kobe Bryant and LeBron James adorn the walls of young basketball fans across the country, it may surprise many Americans to learn that when the NBA was founded, in 1949, there were no black players.

“It’s not not just reading about a basketball player, it’s important history to remember,” Maraniss said. “I think we all need to learn more about that. It’s not just good enough to believe things like you’re progressive or you’re not racist. It’s what are you actually doing, your actions. Perry was surrounded by a lot of bystanders who were not racists. The white students who were on campus at that time would say ‘I’m not the one who called him the N-word’ or hit him in the face. I didn’t do anything.’

“Exactly — you didn’t do anything.

“We all have these choices: Who are we going to help, who are you going to stand up against and when are we going to be a bystander? That’s all true today.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.