How the Santa Clarita Blue Heat became a hotbed for rising women’s soccer stars

- Share via

As Alyssa Thompson grinned and grimaced her way through a series of interviews following Thursday’s NWSL draft, a squat man with a salt-and-pepper beard and black hair graying around the temples stood in the shadows and smiled.

As the first high school player selected with the top pick in the draft and the youngest player to join the national team in more than six years, Thompson, 18, is U.S. Soccer’s newest celebrity phenom, the latest in a list that starts with Mia Hamm and includes 70 women who made their international debuts as teenagers.

The man watching from the shadows played a big role in getting her there.

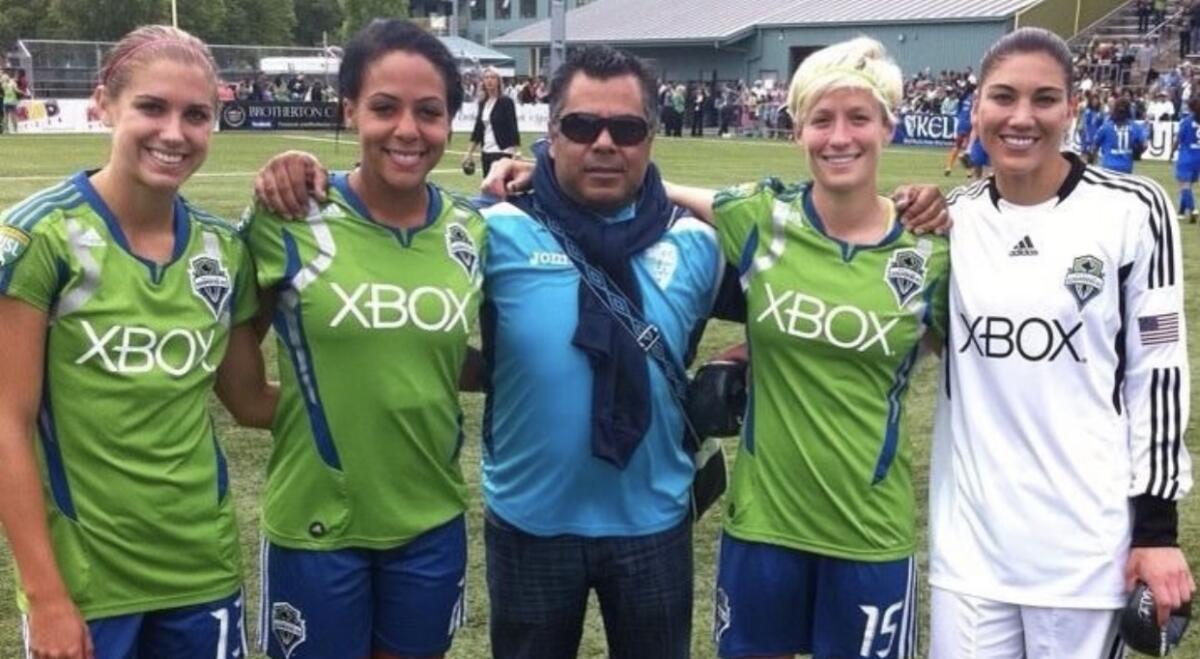

Carlos Marroquin, 55, a former Guatemalan youth international whose career ended in injury before it really got started, runs the most interesting and influential women’s soccer club you’ve probably never heard of. Last season the Santa Clarita Blue Heat’s roster featured a future NCAA champion, national team players from Armenia and Canada, a future Rose Parade queen in Bella Ballard as well as Thompson and her sister Gisele, a starter in the U-17 World Cup last fall.

Harvard-Westlake star Alyssa Thompson becomes the youngest player ever selected No. 1 in the NWSL draft, with the 18-year-old going to Angel City FC.

Past teams have included Venezuela’s Deyna Castellanos, who finished third in voting for FIFA’s women’s player of the year; national team captains from Costa Rica and Portugal; a four-time Finnish player of the year; a Chilean World Cup player who is also a model; and more than a half-dozen college All-Americans.

“It is really nice to know, as a college coach, that we have these [people] such as Carlos that are kind of still looking out for the best interests of our players and really looking out for their health, for their development,” said UCLA coach Margueritte Aozasa, whose program has sent several players Marroquin’s way.

The Blue Heat, which plays in the second-tier United Women’s Soccer league, fill a vital niche in the sport’s landscape, Aozasa said. College and high school coaches are prohibited from working with their players for much of the summer, so teams like Marroquin’s have stepped up to provide a competitive environment for players to continue their development.

“Carlos does a really nice job. He understands the role that those teams play in helping and assisting the college programs, providing players those minutes and games. He’s very accommodating,” said Aozasa, who led UCLA to its second national championship last fall.

“He does a nice job of bringing in top-level talent. So even if the teams they’re playing against aren’t as high level, the players they’re playing with tend to be. We definitely kind of lean on teams like that over the summer because it fills a gap that we really have no control over.”

That wasn’t a role Marroquin envisioned for himself when a visitor to his small Newhall soccer shop asked if he would be willing to help manage a fledging team called the Rooks. At the time Marroquin had little interest in women’s soccer, but he could recognize a disaster when he saw one.

“What I saw was no support,” Marroquin said. “I said we have to do something for these girls.”

A year later, in 2010, Marroquin was approached with another offer. This time he was asked to take over the struggling Ventura Fusion, a women’s team that played in the second-division USL W-League. His reaction was pretty much the same: If he wanted the sport to grow, he had to do something to help. So he accepted the offer, moved the team to Santa Clarita, rechristened it the Blue Heat, and a year later won his first conference title. Marroquin was smitten.

“I started to be in love with women’s soccer,” he said. “I’ve been the solo owner since Day 1. I haven’t had help from anybody. Basically it’s myself.

“When you have passion for something, you keep going. In this division, in this level, nobody’s going to make money. I don’t have any profit. But at least I help girls to be pros.”

Girls like Olivia Moultrie, who used to visit the store with her father when she was in grade school and ask for advice. Now she plays for the Portland Thorns alongside Natalia Kuikka, who helped the Blue Heat reached the UWS championship game in 2017. Ashley Sanchez went from the Blue Heat to the NWSL’s Washington Spirit. Ana Borges went from the Blue Heat to Spanish giant Atletico Madrid, and later to Chelsea.

Yet the best of the lot might be Thompson, who was a skinny, unpolished 14-year-old when she first met Marroquin. Now she’s got a three-year guaranteed contract with Angel City. She was one of seven former Blue Heat players among the 48 women drafted Thursday, with ex-teammate Penelope Hocking also going in the first round when the Chicago Red Stars selected her with the seventh overall pick.

Alex Morgan tops the 24-player women’s national team roster called up for training camp in New Zealand, where the U.S. will open World Cup play in July.

No college program saw more than three of its players drafted Thursday.

Since beginning play in the UWS in 2016, the league’s inaugural season, the Blue Heat have won two titles, the most recent coming in 2021. As much as Marroquin likes winning, that’s not why the team exists. And as much as he’d like to own an NWSL team, his passion lies with players at the start of their climb to stardom, not with those who are already there.

“I had to be realistic,” he said. “I’m never going to be an owner for any professional team. It’s impossible to buy a team myself, and to be part of another team will be impossible. They want people with a lot of money, right?”

So Marroquin helps at the grassroots level, stocking his roster with local high school and college players or European-based pros such as Portugal’s Edite Fernandes and Bulgaria’s Evi Popadinova, who were looking for a place to play.

Now Marroquin has begun using his connections in another way, becoming a U.S. and Latin America scout for A&V Sports Group, a global agency that represents Ballon d’Or winner Ada Hegerberg as well as more than 30 other players — including Thompson — from 13 countries.

“I prefer being a scout because I don’t represent anybody. I send players to good teams,” he said. “I love what I do, I do what I love.”

Ryann Torrero’s journey to the Women’s World Cup began in the back of an ambulance.

It all started with the Blue Heat, which plays a 10-game regular-season schedule in late spring/early summer. The team used venues all over the Santa Clarita Valley before settling at College of the Canyons, where it has begun drawing robust — for the UWS — crowds.

“Before we’d have 50 people in the stadium. Now we have over 500 per game,” he said. “You have 500 people in Santa Clarita at a game, it’s crazy.”

That following has grown because the team has. When your roster annually includes future national team players like Sanchez and Thompson, that helps with marketing the team.

“The team is starting to get more prestigious. People are starting to have more interest,” Marroquin said. “So the coaches from D1 are starting to trust me. When you start something, it’s hard to trust somebody.

“We are the future pros. You want to see somebody next year playing pro, this will be a good chance. They play for us first, and then they play pro.”