Column: After 75 years, baseball in Bakersfield has struck out

- Share via

Reporting from Bakersfield — The modern ballpark is tucked into an entertainment district, with shops and restaurants surrounding the stadium, and blindingly bright digital display signs wherever you look. The ballpark here is across Chester Avenue from Big Valley Mower, Extra Space Storage and AAA Tire. The large sign welcoming you to Sam Lynn Ballpark is home to a few too many cobwebs, and to a weathered gold banner with a simple message for folks driving by: GAME TODAY.

There is a game Sunday, the last one scheduled at a ballpark that opened in 1941. The Bakersfield Blaze is going out of business, not by choice.

In a world with happy endings, this would be a story about the last homestand of the old ballpark, and the anticipation for the move into a new ballpark. But decades came and went, and plans came and went, and the new ballpark never came.

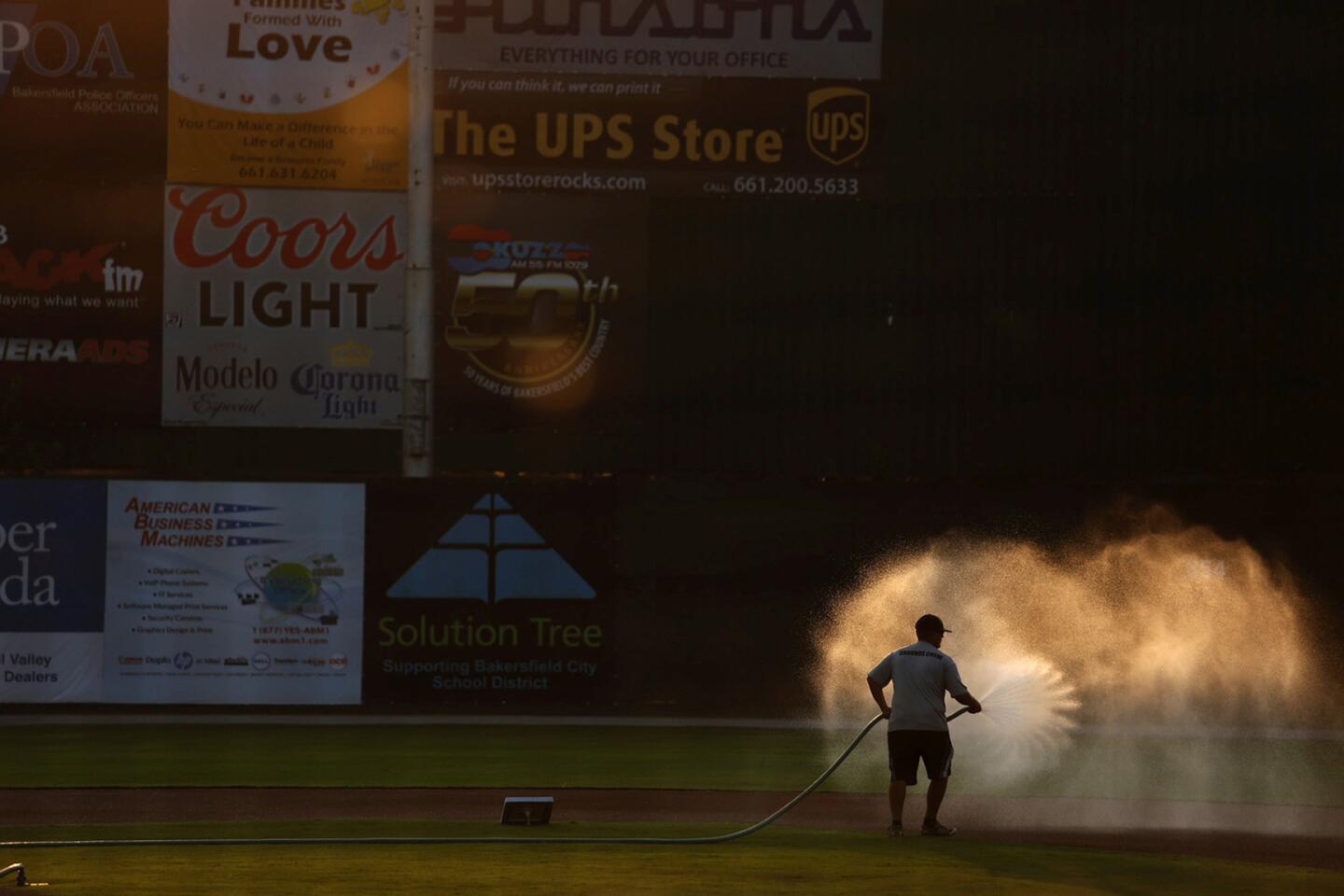

No ballpark does Late Night at the Ballgame quite like this one. The sun sets directly into the eye of the batter. No one much cared 75 years ago, when Bakersfield converted the old county fairgrounds into a ballpark and the team played day games.

Now, the games do not start until the sun sets, so first pitch is pushing 8 p.m. on the longest days of the year. They tried to block the setting sun by putting up a 50-foot-high screen behind center field, but it turned out the screen needed to block a little more of left field and a little less of center.

That screen became another quirk here, just like the scoreboard. Turn it on, and the scoreboard automatically credits the visiting team with no runs in the fifth inning, and the home team with seven runs in the seventh.

The scoreboard made its debut here in 1982, the same year Mark Langston played here. Langston retired 17 years ago; the scoreboard never did.

“I’ll get to tell stories to my grandkids someday about the six years I spent at the weirdest ballpark in America,” said Dan Besbris, the assistant general manager and team broadcaster.

It’s different. That’s what’s cool about it. There’s a lot of character in this place.

— Justin Seager, older brother of Dodgers shortstop Corey Seager

The playing surface is first class. The stadium lights are not. The dugouts are beyond the bases, so it is a long walk from the on-deck circle to the batter’s box.

“It’s different. That’s what’s cool about it,” said Bakersfield infielder Justin Seager, older brother of Dodgers shortstop Corey Seager. “There’s a lot of character in this place.”

This is minor league baseball at its foundation, a place for players to build careers and fans to build community. The seats are functional, not lavish. But where else can you see a professional baseball game and buy bottled water for $3, Cracker Jack for $2 and, on Mondays, tickets for $1?

On one night, the home team dressed in SpongeBob SquarePants jerseys. On another night, fans got throwback Bakersfield Outlaws shirts, cheekily sponsored by Gotta Go Bail Bonds.

The Dennis “Froggy” Gallion gate at home plate is named not for a famous player or a local dignitary, but in honor of a beloved guy who has sold game programs here for a couple decades. The booster club has disbanded, but the old gang is getting together Sunday afternoon to throw a baby shower for Besbris and his wife, Jessica. (Surprise, Jessica! Your husband thought it would be really cool to reveal the surprise in this column.)

Dodgers catcher Yasmani Grandal played here five years ago. He became so close with team chaplain John Carter that he flew him to Florida two years later so he could officiate at Grandal’s wedding.

Grandal and Carter still talk every Sunday. When Minor League Baseball extinguished the Blaze last week, the chaplain texted Grandal to let him know.

“I still talk to a bunch of people there,” Grandal said at Dodger Stadium last week. “It’s a little sad to hear that baseball is getting away.”

It is also sad to say that Bakersfield might not miss its baseball team all that much. The team has ranked last in the Class A California League in attendance in each of the last 10 years and has not averaged even 1,000 fans per game since 2007.

Major league teams want the finest facilities for their minor league players, and Bakersfield became something of a consolation prize for teams that could not find a more modern home elsewhere. The Seattle Mariners, Cincinnati Reds, Texas Rangers, Tampa Bay Devil Rays and San Francisco Giants all sent players here within the past two decades; none of those affiliations lasted more than six years.

In 2013, the Blaze was so close to securing a new ballpark that Besbris already had written the press release announcing the groundbreaking, but the owners failed to finalize the financing and sold the team instead. In 2014, the team was close to moving to Salinas.

This year, when the Adelanto City Council tried unsuccessfully to evict the High Desert Mavericks from their ballpark, Minor League Baseball pounced. Since moving two teams is easier than one — a league needs an even number of teams for scheduling purposes — Minor League Baseball essentially bought the Blaze and Mavericks, then sold them to owners who would place the teams in the Carolina League.

“To have baseball there that long and then to take it away, what is the city left with?” said Dodgers pitcher Jesse Chavez, who played here in 2005.

Minor league hockey does well here, in a new arena. It is difficult to imagine that minor league baseball would not do well here — in a new ballpark with modern amenities, and in a part of town closer to the population growth.

“This is a triple-A market,” said Blaze General Manager Mike Candela.

Indeed, Bakersfield has a larger population than Anaheim, and the Pacific Coast League might be a more logical home for a revived Bakersfield team than the California League. This might be wishful thinking, but what locals really hope for is a new ballpark that could lure the Dodgers’ triple-A team, currently in Oklahoma City.

The Dodgers have affiliated with Bakersfield three times, dating back to when the Brooklyn Dodgers sent Don Drysdale here. The Blaze yearbook calls the last Dodgers affiliation (1984-94), in which Pedro Martinez, Mike Piazza, Eric Karros and Raul Mondesi played here, “the golden era of baseball in Bakersfield.”

In the meantime, a town that ignored the Blaze all summer has swarmed the old ballpark to say farewell. Friday’s game sold out. So did Saturday’s. The team store has been cleaned out of just about all of its merchandise, including those SpongeBob jerseys and a roll of unused Bakersfield Dodgers tickets from three decades ago.

Bakersfield is on pace to qualify for the Cal League playoffs, so no one knows for sure when the last game here will take place. After it does, the team will donate a few memories to the Kern County Museum, and then the eight full-time employees will be out of work.

Jeff MacDonald, the director of stadium operations, is the one responsible for putting up the “GAME TODAY” banner on the big sign along Chester Avenue. He puts the banner up, and he takes the banner down, all summer long. He does not use a ladder.

“I take an ATV out there,” he said, “and jump on top of the ATV.”

He might remove the banner after the last game and take it home to Michigan with him. Or he might just leave it there, a reminder to folks driving by that this town has lost a little bit of its soul.

Twitter: @BillShaikin

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.