- Share via

In “The Last Dance,” the 10-part documentary that details Michael Jordan’s career, Kobe Bryant says “What you get from me is from him. I don’t get five championships here without him.” The comparisons between the two were there from the start, as relentless as their playing styles. This excerpt from “The Rise” details the birth of a relationship between two icons.

Both on the court and off it, Kobe Bryant was a thirteen-year-old version of the twenty-three-year-old version of Michael Jordan, believing that he could do it all alone, that he was his team’s only hope and salvation, that passing was inherently unproductive, every shot he took acting as a salve for his own ego. Jordan did not win his first NBA championship until his seventh year in the league, until June 1991, before Kobe had entered eighth grade. The Jordan who would go on to win six NBA titles, who learned to trust John Paxson in the final minute of one championship-clinching victory and Steve Kerr in another, who gave in to Phil Jackson and Tex Winter and the selfless cohesion inherent in the triangle offense and saw his game flourish for it, had just emerged, just broken through his chrysalis.

So why not allow Kobe to see, up close, this fuller iteration of Jordan? His father, Joe, as a former NBA player, could make that meeting happen. Joe could get Kobe into the Spectrum when the Chicago Bulls came to Philadelphia to play the Sixers.

And he did. Before the teams’ game on March 8, 1992, father led son into the arena’s locker room, and Kobe said hello to Michael Jordan. Jordan said hello back and gave him a wristband. There is no lasting indication that Kobe was nervous or stuttering or in any regard intimidated by Jordan. That was merely the entirety of their conversation; Jordan had nothing else to say. Neither did Kobe, who introduced himself to Bulls forward Horace Grant.

“Do you play basketball?” Grant asked him.

“Yes,” Kobe said, “but I’m only in eighth grade.”

“Are you going to be a superstar one day?”

“Yes,” Kobe said, “I might be.”

::

Fast forward two and a half years. By the fall of 1995 and the start of his senior season at Lower Merion High School, Kobe had all but made up his mind that he would skip college and declare himself eligible for the 1996 NBA draft.

The media . . . it was easy to hide his true thoughts from them, just smile and deflect and mention one more time how much he had learned from his father about the process, how fun it was, how he was taking it all in. The chances that he would change his mind were slim, but he was happy to keep his options open — “Never say never, may go down there, have the best time of your life” — and to listen to him answer questions about his decision was to recognize, just from the tone and inflections of his voice, that he delighted in the speculation. It was a game to him, stringing people along, keeping them guessing.

He liked Villanova, Michigan, and Arizona. Villanova? It would be cool to play close to home, with Tim Thomas. Michigan? Man, he loved Jalen Rose and the original Fab Five. Arizona? He had become friends with one of their recruits, Stephen Jackson. But none of those connections or reasons was strong or profound enough to get him to go to any of those schools, and with the exception of Duke and Mike Krzyzewski, whom he talked to by phone here and there, even college basketball’s blue bloods were standing on tiptoes outside Kobe’s window, hoping he’d see them.

Kentucky? Rick Pitino couldn’t get Kobe to visit Lexington, so he did what he thought was the next-best thing: He got Kobe’s coach, Gregg Downer, to visit Lexington, flying him down there for a weekend. Downer, who had long admired Pitino, watched the Wildcats practice and toured the campus and the town, but it didn’t do Pitino much good in changing Kobe’s mind.

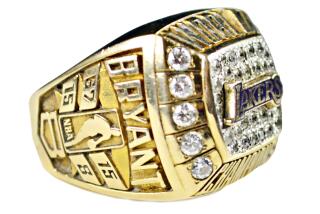

L.A.-based artist Victor Solomon helped redesign the NBA’s All-Star weekend trophies, including the ASG game MVP trophy in honor of Kobe Bryant.

North Carolina? Kobe had received a recruiting letter from Dean Smith and had been so thrilled — Dean Smith! — that he had opened the envelope in English class while his teacher was droning on. But if he chose North Carolina, he would be choosing Michael Jordan’s alma mater, and as much as he admired and emulated Jordan, how could he, Kobe Bryant, have his own identity there? Besides, Smith had cut to the chase: We know you’re turning pro, but if you change your mind, there’s a scholarship here waiting for you.

“Everybody’s on the ground, wanting to know what school he’s going to go to or hey, maybe he might go to the NBA,” Kobe’s friend Anthony Gilbert said, “and Kobe was on the bird’s-eye view of that. Everything is a litmus test, and everything he’s doing, he’s assessing and testing. ‘Yeah, naw, college ain’t for me.’ Dean Smith actually smelled it and was like, ‘Naw, you’re not coming here, dude.’ UNC wanted him, and they got to a point where they were like, ‘OK, we’re not getting you, dude. You’re clearly not going to college.’ And that was Dean Smith.”

::

Fast forward another six months. Kobe got another chance to interact with Jordan in March 1996.

It was a night for Kobe to hang out with old friends, to pal around with his summertime pickup-game buddies, Jerry Stackhouse and Vernon Maxwell, in the home locker room of the Spectrum, a couple of hours before the 76ers’ game against the Chicago Bulls. Sixers coach John Lucas had invited Kobe to the game, all the better to maintain and strengthen their relationship as the NBA draft, still three months off, approached. Now Lucas interrupted the conversation with Stackhouse and Maxwell with an offer that Kobe couldn’t refuse. Let’s go meet Michael. Lucas led Kobe to the visitors’ locker room. A horde of reporters encircled Jordan. Kobe slid up as close as he could and leaned against a nearby wall.

The current generation of NBA stars, including Klay Thompson, Trae Young and Jrue Holiday, talk about Kobe Bryant’s influence on the game of basketball.

“Kobe,” Jordan said, “what’s up?”

Kobe looked around. Is there another Kobe here? I know he’s not talking to me.

Jordan extended his hand. “Hey,” he said, “nice meeting you, young man.”

Kobe didn’t know that Jordan knew anything about him. Did he remember their brief interaction when Kobe was an eighth grader? Had Lucas mentioned something to him? Had Jordan heard or read about him? Kobe reached out his hand and shook Jordan’s. His hand is so . . . strong . . . Kobe was not nervous. This person standing in front of him, this person whom the world adored, was a human being, just like everybody else. Just a basketball player, like Kobe.

Unlike in their previous meeting, Jordan this time talked to Kobe at some length. Enjoy the game, he told him. With the pressure and hype that’s going on, you can become easily distracted, and the game won’t be enjoyable. Don’t let people do that to you. Stay yourself. Have fun on the court, and everything will be fine. The last piece of advice Jordan gave him: Man, if it was up to me, you’d go to North Carolina. Go to Carolina. He said it three or four times, having no idea, of course, that Kobe already had made up his mind about the NBA, that he already had said to his mentor and English teacher Jeanne Mastriano, “The window’s closing. I’m not going to have a chance to play against Michael if I don’t go now.”

The sands of power and popularity in an institution, in a culture, can begin to shift without anyone noticing. The Bulls, on their way to a seventy-two-win season and the fourth of their six championships with Jordan, beat the Sixers, 98–94. Kobe’s introduction to him merited nothing more than a throwaway line in a Philadelphia Inquirer feature a couple of days later: “There was also an audience with Michael Jordan on Monday.” To fashion a stronger link between the two of them then, between the most famous and admired athlete in the world and a seventeen-year-old aspirant, would have been absurd.

And yet, remember: Just two years separated Jordan’s last NBA championship from Kobe’s first. The transition from one to the other was more direct than anyone could have imagined in 1996, and by 2020, Jordan had felt enough of a need to reaffirm his standing in the sport, to reacquaint everyone with his magnitude, that he partnered with the NBA for the ten-part ESPN documentary The Last Dance.

“What you get from me is from him,” Kobe says during the series. “I don’t get five championships here without him.” There is a subtle but telling detail in the interview: At the instant that Kobe utters those words, he moves his right hand as if he is pushing away either the interviewer or the question, as if he is saying, Slow down. Don’t forget. Michael came first.

The reminder is necessary, not because Kobe had surpassed Jordan as a player, but because he had surpassed him as a story. He had traveled the redemptive narrative arc: ruining his good name and nearly his marriage and leaving a stranger scarred in that hotel room in Eagle, Colorado; destroying relationships with who knows how many coaches and players and peers before reconstituting them; somehow scrubbing away much of that grime to emerge as someone perceived to have matured, to have found the elusive balance between peace and ambition; persuading people that the arrogance and atrocious choices and actions of his past weren’t so relevant anymore; forging a new identity as an emotional and psychological touchstone, the possessor of a mentality that all should admire and emulate and adopt. It was a greater trick than all the rest.

From “The Rise” by Mike Sielski. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press. You can purchase the book here.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.