- Share via

LeBron James stood in front of a Lakers backdrop in the NBA’s bubble near Orlando, Fla., after his first game of the season restart back in July, listening to a question asked thousands of miles away from Los Angeles: What had he hoped to accomplish?

The Lakers star answer revealed less about the evening’s exhibition and more about what he and the NBA hoped to accomplish in the next three months.

“First of all,” James began, “I want to continue to shed light on justice for Breonna Taylor and to her family and everything that’s going on with that situation.”

For the next 13 minutes, James called for Louisville police officers to be arrested in the death of Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician killed when officers entered her home on a “no-knock” warrant as she slept. He discussed Black Lives Matter and the change he wanted to see in America. Basketball barely was broached.

Just as his answers reflected the fraught backdrop — the combination of a pandemic and a national reckoning on racism —in the bubble, James also foreshadowed the way players and coaches would spend the coming months reframing basketball conversations. Their broader discussions of social justice on topics including voter suppression, police brutality and systemic racism would become sharply focused on those problems.

“Two years ago, you think you would have been interviewing NBA people about racism and racial equality and to be able to say it openly and confidently and to put ‘Black Lives Matter’ on the court?” Atlanta Hawks coach Lloyd Pierce said. “Those things were impossible in any sport two years ago because of the difficulty to confront racism and racial equality. The necessary side of having these conversations has at least gotten us to this point.

Complete coverage from the Lakers’ championship season

“First and foremost we have to address it. Second, we have to make sure that people understand and are affected and are impacted and bothered by it. Now that we have this huge amount of support, what can we do?”

Dr. Harry Edwards, the sports sociologist who has advised athletes on activism for six decades, said the advocacy in the bubble fit into what he called the “fifth wave” of athletes’ activism, one defined by their keen understanding of their power, and how to wield it.

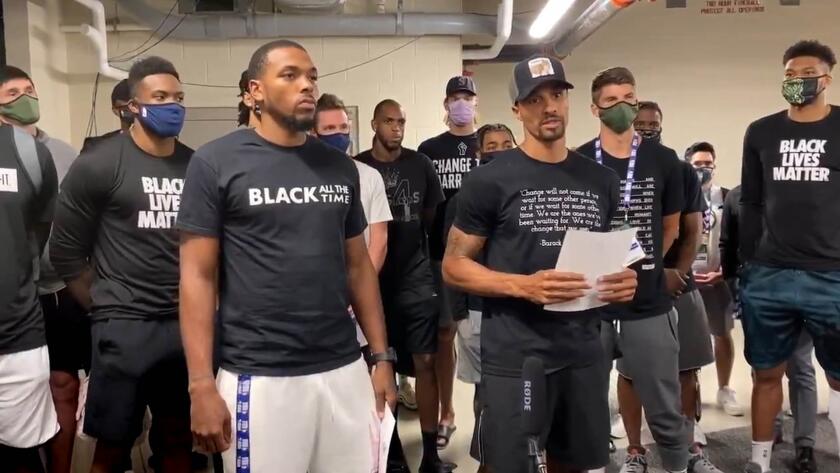

Edwards was not surprised to learn that the Milwaukee Bucks, after sitting out an August playoff game as a protest following the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wis., made a public statement only after reaching Wisconsin’s attorney general and lieutenant governor by phone, asking how they could help. Their strike led to a league-wide walkout that paused games for three days and ended with the NBA and its owners committing to turn their arenas into voting centers, and the creation of a social justice coalition.

One of the strongest stances taken this summer came in the WNBA, where players wore T-shirts urging Georgians to vote out incumbent Sen. Kelly Loeffler, a co-owner of the Atlanta Dream who said she opposes the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Even though none of these players, none of these leagues, are in the social justice business, this stuff has come over the stadium wall, through the pavilion, through the locker room, and they must be intelligently managed because they can be neither eliminated nor avoided,” Edwards said. “And this will not be the last time.”

The NBA collectively spent its summer preparing its response for the next time, with teams and players intertwining themselves with various social-justice efforts.

In June, James helped launch the nonprofit “More Than A Vote” to fight voter suppression in states including Georgia, Texas, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. Twenty-one arenas, including Staples Center and the Forum, will serve as voting centers. In August, the NBA said owners could collectively contribute $30 million annually for a decade to fund its newly created NBA Foundation with a mission “to drive economic empowerment for Black communities through employment and career-advancement.” Rep. Karen Bass, the leader of the Congressional Black Caucus, spoke virtually with the Clippers in September about the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act and how they can raise awareness about police-reform legislation. Chris Paul, president of the players’ union, said this month that more than 90% of NBA players had registered to vote.

“I think our handling of the NBA with the COVID situation has been tremendous. I would like to see our handling of racial equality and opportunity be tremendous, as well.”

— Lloyd Pierce, Atlanta Hawks coach and head of NBA coaches coalition

- Share via

The Milwaukee Bucks refused to play Game 5 of their NBA playoff series against the Orlando Magic in the aftermath of a police shooting 40 miles from their home arena, leading the NBA to postpone the games scheduled for Wednesday.

“We need to get people out to vote. I urge you to,” Lakers guard Danny Green said, days before his team’s championship. “Can’t emphasize it enough. That’s what’s more important.”

Though the Hawks were one of eight teams not invited to the bubble because they had been eliminated from playoff contention, Pierce was nonetheless “extremely busy” working the phones this summer. As chair of a new committee of the National Basketball Coaches Assn. focused on racial justice, Pierce sought to use coaches’ influence to shape nonpartisan policy reform and build inroads into their communities. He said it was as united as he’d seen the league since commissioner Adam Silver banned former Clippers owner Donald Sterling for life in 2014 for making racist comments.

Everyone wants to identify tangible steps, Pierce said, but there is no playbook for tackling systemic racism. Coaches’ plans to connect with grassroots organizations in their communities have been difficult to implement, Pierce said, because coronavirus restrictions limited coaches’ natural strengths: gathering and rallying groups.

“It’s really how can we join in on the positive side, the solution side, of creating equality in our league and being a model of equality, where we have to internally address some areas of concern that we may have and then also rally together and come up with creative ways to be a model?” Pierce said. “I think our handling of the NBA with the COVID situation has been tremendous. I would like to see our handling of racial equality and opportunity be tremendous, as well.”

Not every plan has gone smoothly, nor has every sentiment been lauded.

The George Floyd bill passed the Democrat-held House in June but has stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate. As quickly as Wisconsin’s legislature reconvened for a special session days after the Bucks’ action, lawmakers went home without taking up police reform bills. Local election officials in Miami and Milwaukee opted against using the arenas as voting sites, despite the urging of the teams. In September, Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva said that athletes, among others, should promote trust of police rather than “fanning the flames of hatred,” and challenged James to contribute to a reward for an attacker who ambushed a pair of deputies. James declined to address the comments but said he never has condoned violence.

When players such as Carmelo Anthony and teams including the Clippers and Oklahoma City Thunder asked Edwards this summer for ways they could use their visibility to combat racism, he suggested channeling their energy on mobilizing voters to elect candidates who could help under-represented voices get “a seat at the table.” Indeed, much of the NBA’s social justice response is centered on November’s election.

But progress on social justice requires more than a vote, Edwards said.

“It’s about follow through,” he said. “The name of the political game is the same as the name of the game on the court and on the field: You can’t go on the court, jump center, and then just relax.

“We can’t put people at the table who are going to listen to us and then we just walk away because it’s no longer basketball season or because we’re dispersed all over the country and no longer in Orlando anymore. What are we going to do?”

As the Lakers left the bubble this week, more than three months after arriving, they carried the franchise’s 17th title into an outside world that has calmed little, if at all, since they entered their seclusion.

It was why, as confetti shaped like the championship trophy settled at his feet Sunday in a mostly empty arena, James said he had not yet accomplished all he had set out to do.

“We know we all want to see better days, and when we leave here we got to continue to push that,” James said. “Continue to push [against] social injustice, continue to push [against] voting suppression, continue to push [against] police brutality, continue to push [against] everything that is opposite of love. If we can continue to do that, all of us, America will be a much better place, which we all love this country.”

Grief reported from Los Angeles.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.