Column: Rafer Johnson hopes his legacy inspires others to be their best

- Share via

Outside the modest Sherman Oaks home of Los Angeles’ most unassuming sports legend hangs a flag.

It is not a flag of a team or an accomplishment, but of a mission.

“Love,” it reads.

Inside, Rafer Johnson, 83, an athlete whose life both literally and figuratively lit a flame, speaks of his legacy with a gentle smile.

“I want people to remember that I appreciated the opportunity to be of help and service,” he says.

He leans back in a chair surrounded by a testament to the noticeable fact that he did not mention a single personal accomplishment in that answer.

Examining the famous Rafer Johnson’s home, one would have no idea that the famous Rafer Johnson lived there.

His 1960 Olympic gold medal in the decathlon, anointing him as the greatest athlete in the world at that time? It’s nowhere to be found.

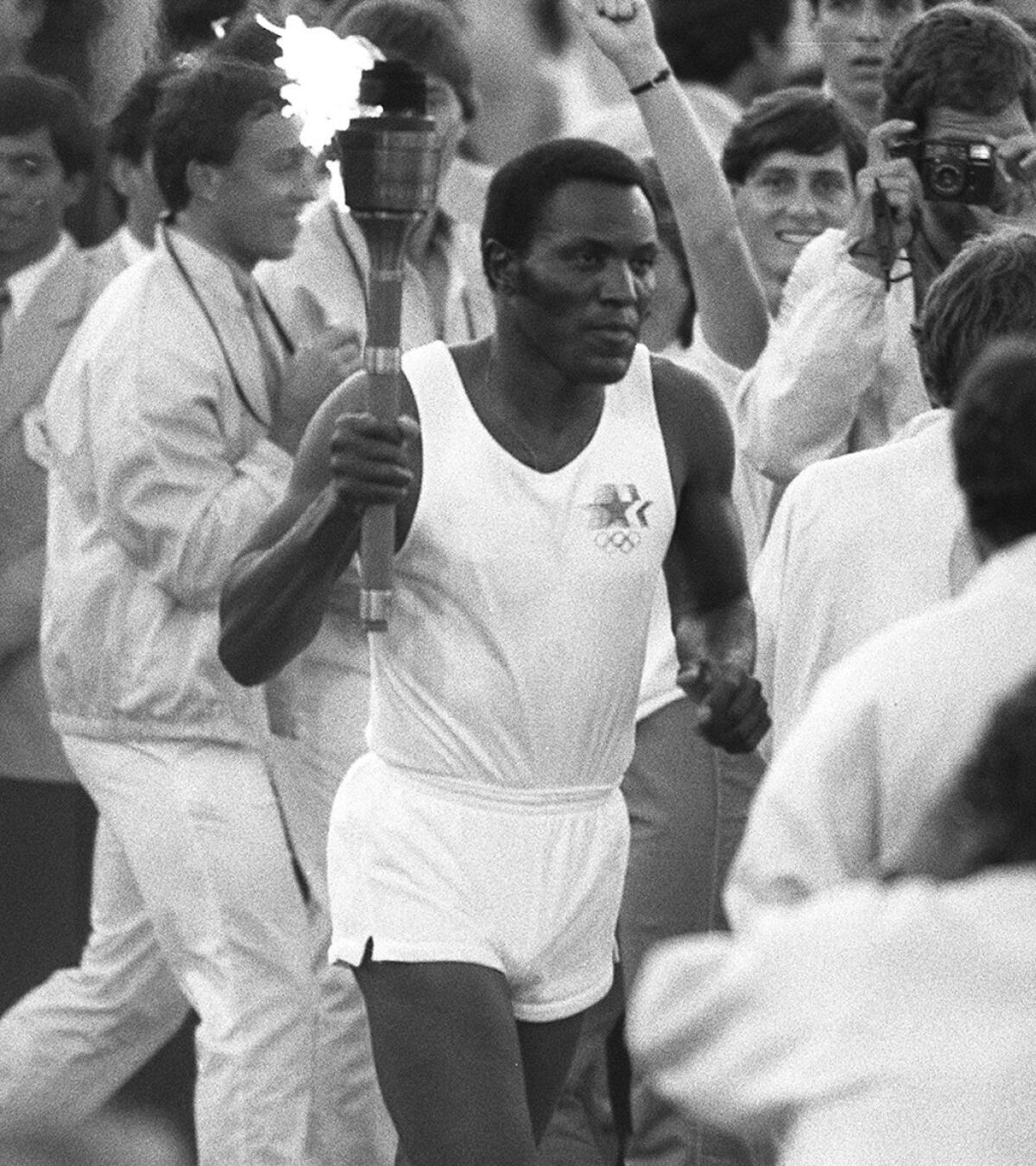

The torch he used to light the 1984 Olympic flame in Los Angeles, symbolizing the beginning of the greatest sporting event in this city’s history? No sign of it anywhere.

His role as one of the co-founders of the California Special Olympics 50 years ago? Not a shred of evidence.

In fact, there is not one trophy or plaque or medal or any memorabilia from his memorable sporting life anywhere in the actual home. The walls and mantle are instead decorated with family photos, children’s drawings, a sign that reads, “Welcome Home Bapa.” In the middle of the family room floor is a trampoline. Cluttered around it are toys.

He and Betsy, his wife of 47 years, live amid the trappings of two grown children and four grandchildren, a daily tribute to their true gold.

“I never let anything reduce what I treasured most, and that was being with my family,” Johnson says.

So Johnson spends his days in relative obscurity, one of this city’s hidden gems, rarely visible beyond quietly attending sporting events at his beloved UCLA.

“I spent a lot of time being as helpful as I could, for people who needed a little help, and this is how I ended up,” he says with another smile. “This is good.”

He lives without any of the modern trappings that could be used to capitalize on a life rich with history. He doesn’t have a smartphone. He doesn’t have a laptop. He doesn’t use the internet. He even stopped answering autograph requests that arrived in the mail when he was told that somebody had attempted to sell one of his autographs on Ebay.

“My Dad never wanted to be something he wasn’t,” says his son Josh, a former UCLA javelin star who works in commercial real estate. “He was never into outside things. He was into family. He was into helping people.”

All of which makes the current exhibit at the LA84 Foundation house so special because it shines a light on Johnson that he would never shine on himself.

The display is titled “Rafer Johnson. His Life. His Impact.” It opened last month in honor of Johnson ending his 34 years as an LA84 board member and moving into an emeritus position.

“He’s been truly the moral compass and the North Star for our organization,” says Renata Simril, president and chief executive of the LA84 Foundation. “We want everyone to know what a great man Rafer Johnson is, and our responsibility is to tell that story so people don’t forget.”

The exhibit follows Johnson’s life from his days as a child picking cotton in rural Texas while living in a house with no plumbing or electricity, to a UCLA basketball player under John Wooden, to the office of UCLA student body president, and on to the Olympics as a decathlete who won a silver medal in 1956 before being triumphant in Rome in 1960.

It also documents his close friendship with the late Robert F. Kennedy, and how he was with Kennedy on June 5, 1968, when Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. It was Johnson who helped grab the gun from the assassin Sirhan Sirhan in an event so frantic, Johnson instinctively put the gun in his pocket and didn’t realize it was there until he returned home that evening.

The grieving over the loss of his close friend led to him joining Eunice Kennedy Shriver, Kennedy’s sister, in overseeing the first Special Olympics in Chicago a month later. This led to Johnson helping form the California Special Olympics, which has affected millions.

“He’s been critical not only to Southern California, but to the world,” says Simril. “With him it’s never been about the being in the limelight. It’s been about, ‘How much impact can I have on other people?’”

Johnson has so eschewed that limelight, his wife had to scour the shadows to find the memorabilia for the exhibit. She looked in the garage, looked in storage units, and helped arrange the exhibit without much assistance from Johnson himself.

“I told everyone, ‘This is what’s going to happen,’ because he is so modest, he would never come up with an idea like that,” she says.

The opening ceremonies for the exhibit at the downtown LA84 Foundation house on the final Sunday of April contained speeches from sports figures and statesmen, from UCLA gymnastics legend Valorie Kondos Field to Bobby Kennedy Jr. to Mayor Eric Garcetti.

“Thank you for being an angel in the City of Angels,” said Garcetti.

To the surprise of no one, seemingly the only famous person in the place who didn’t speak was Johnson himself.

“I was blown away by the whole process,” he says. “I was happy just to talk with all my friends.”

Equally blown away were his children during a private showing before the ceremonies. Because he never talked about his accomplishments while they were growing up, they were awed when witnessing the collective scope of his impact.

“It was extremely emotional, a lot of tears of pride,” said his daughter Jennifer Johnson Jordan, an assistant coach on UCLA’s national champion beach volleyball team. “The full testament to the life he led was amazing to us. Growing up, there was no conversation about what he had done.”

He was so humble, he didn’t even tell his children he was lighting the torch in 1984 until they were driving to the Coliseum for the opening ceremonies.

“Then throughout the Olympics, he was mobbed by people, that’s when we knew the world viewed him as something special,” says Josh.

Many folks think Johnson’s most famous steps were the ones he climbed in the Coliseum that summer night in 1984 to light the torch. His family remembers different steps, the ones he took to attend all of their childhood sporting events, as a fan and a groundskeeper and a concession worker and a Dad.

“He was always the one out there setting things up for the fair, the first one to work on cleanup days, the one who put the soccer goals up and took them down,” says Jennifer.

He would do everything from coach their games to insist on properly tying their shoes. Somewhere there is a closet full of VHS tapes documenting all of their youth league accomplishments. Even more inedible is the story about how he was once willing to be ticketed and towed just to see one of their games.

It was a time one of their games made him late for a flight to a speaking engagement. In an attempt to make the plane, he rushed to LAX and left his truck in front of a terminal. He made the flight, the truck was towed, and he didn’t care.

“It was worth it,” he says. “The kids were always worth it.”

Some folks also remember his acting roles in several movies, mostly in the 1960s. His family, however, remembers him being a bigger star to the competitors in the Special Olympics, which he would work consistently, once again doing everything from hugging the athletes to selling the sodas.

“We lived through his service to others, we were always involved in community events,” says Jennifer. “Working for something like the Special Olympics was always more important to him than any of his own accomplishments.”

It is this work that Rafer Johnson hopes will be his lasting legacy for future athletes. He sees the riches they have earned, riches he was often denied because of the color of his skin, and he wonders why they aren’t giving back more.

“The athletes today, they are able to make a contribution in a substantial way, and more are doing that, but some are doing nothing or very little,” he says. “I think they all ought to be doing something significant. They have the power. They are in a position to inspire others.”

In his long and illustrious life, Rafer Johnson has inspired everything and everyone except, apparently, those who hand out awards and draw up lists.

Of the 33 sports figures who have been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom — the nation’s highest civilian honor — Johnson is stunningly not one of them. Seriously, how can that be? Tiger Woods but not Rafer Johnson?

Among polls of the greatest sports figures in Los Angeles history, Johnson is amazingly not listed near the top. If the former world’s greatest athlete and California Special Olympics co-founder doesn’t rate, who does?

Yet it’s fine with him. There’s no bitterness here, no angst, no regrets. There’s only that constant gentle smile as he sits among the reminders of a life well served.

“I wanted to make the best contribution to life I could make,” Johnson says. “I didn’t just want to be good, but I wanted to give others the feeling that they could also be as good as they could be.”

Just like the flag says.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.