Column: Dodgers Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin is a Los Angeles legend

- Share via

Everywhere he goes, he is serenaded, by restaurant busboys and city officials, from the bleacher seats to the dugout club, his life reflected in the singing of a call that has become a connection.

Se va, se va, se va ...

Jaime Jarrin softly smiles. He hears their voices, sees their faces, understands the bond, embraces a meaning far more powerful than a home run.

“I never wanted to be someone who only called the action,’’ he says. “I wanted to serve the community.’’

It’s going, going, going ...

For 60 years as the Dodgers Spanish-language radio broadcaster, Jarrin’s journey has imitated the flight of long fly balls he describes with such flourish. Sailing into the winds of tragedy and stereotype, his words have reached beyond the field, carried into the stands, and become the bridge between the Dodgers and their largest community.

“In many Latino homes, Jaime Jarrin is like a member of the family,’’ says Jose Alamillo, professor of Chicana/o Studies at Cal State Channel Islands. “He’s invited people into the Dodgers. He has given them a connection.’’

That connection has come at a cost, Jarrin’s grandfatherly sweetness masking a lifetime of struggle.

Jarrin, 82, will celebrate a milestone anniversary this season as the longest-tenured announcer in baseball, and one of only three Spanish-language broadcasters in the Baseball Hall of Fame. But his crew for a time was occasionally treated like second-class citizens in opposing stadiums, sometimes seated in makeshift booths or behind outfield fences.

“Once at Candlestick Park, I was seated behind home plate yet Jaime was far down the left-field line, he was almost out of the ballpark,’’ Vin Scully recalls. “I remember telling him, there will come a day when, in every ballpark, you will be behind home plate where you belong, because you deserve it.’’

Jarrin was part of baseball’s first Spanish-language broadcast team, and has been celebrated as a Dodgers pioneer. Yet, six years ago, the Frank McCourt-owned Dodgers initially did not include Jarrin in a promotion featuring bobblehead dolls of 10 Dodgers greats, hastily adding him only after receiving bad publicity.

“Even now, when it comes to the importance of the Spanish-language broadcast, some people still don’t get it,’’ Jarrin says. “They just don’t understand our audience.’’

Jarrin, who once worked nearly 4,000 consecutive games, endured the sudden death of his 29-year-old son, Jimmy, and survived a near-fatal auto accident that left him with injuries that linger nearly 20 years later.

When he became an announcer in 1959, Latinos made up less than 10% of the crowd at Dodgers games. Now, while there are no official statistics, Latinos are a clear majority, and Don Jaime a rock star.

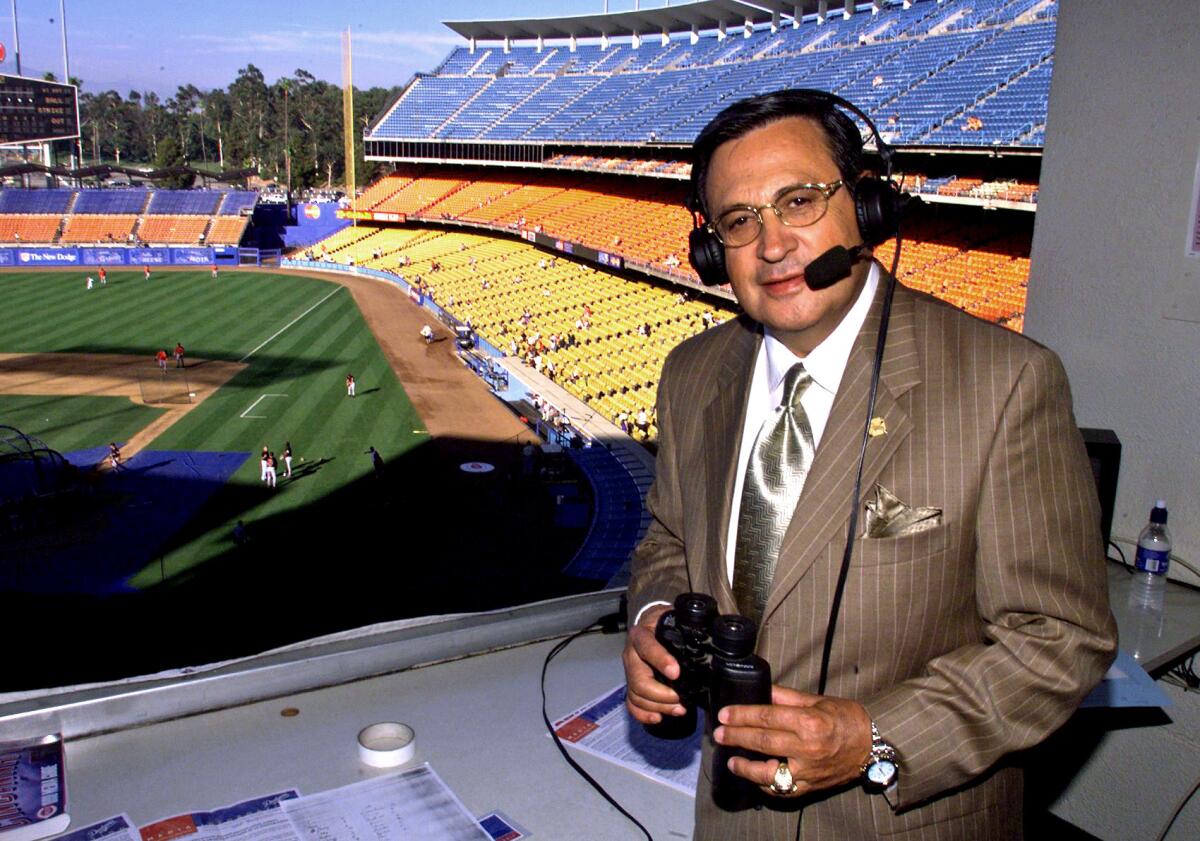

When he walks the concourse during his middle-inning break, he is surrounded by fans and stadium workers, folks coming out of the backs of kitchens and the fronts of restaurants to meet the man in a stylish suit and professorial glasses.

“He is more than just a Dodger broadcaster, he is more than just their voice for the Spanish-speaking community,’’ says Orel Hershiser, a fellow Dodgers broadcaster. “The way he treats everyone from the superstar to the usher, all with such dignity and class, he is a top Dodgers role model for all of Los Angeles.’’

Jarrin is known by some fans from his three decades of commercials for the Los Defensores legal services firm — he spins the phone number like he is calling a no-hitter. He is known for his work as Fernando Valenzuela’s interpreter in the early 1980s, when the 20-year-old pitcher fueled Fernandomania.

But he is best known in the Latino community as the voice that brought baseball into their homes. Alamillo said his father Jose would return summer nights from his job picking lemons, turn on the radio, and fill the house with Jarrin.

“Jaime was a staple in our home, and in many other Latino homes, the first voice who brought us the Dodgers,’’ says Alamillo, who is involved in the Latino Baseball History Project, which documents the baseball histories of Latino communities throughout the country. “He’s played a big role in bringing a lot of Latino fans into the stands, making people more comfortable, inviting them to join in. Those radio broadcasts created a real sense of community.’’

Jarrin found his voice after immigrating to Los Angeles at 19 from Quito, Ecuador. He arrived June 24, 1955, the date of Sandy Koufax’s first career start. But he is honest enough to note that, at the time, he knew nothing about Koufax and didn’t understand a thing about baseball.

“There was no baseball in Quito at the time, none,’’ he says. “I knew nothing about it.’’

His first job was as a laborer at a metal fence factory in East L.A. His first home was a rented room for $4 a week. He couldn’t afford an automobile, so he rode the streetcars. He didn’t speak English, so he took classes.

He had worked at a radio station in Quito, so he was able to find a job reading news at Spanish-language KWKW in Pasadena. Three years later, when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958, owner Walter O’Malley enlisted the station for its landmark Spanish-language broadcasts.

Jarrin recognized baseball’simportance in America and wanted to be part of it, but he had never seen a major league game in person. He was hired as the Dodgers’ No. 2 Spanish-language announcer, but was ordered to spend a year on the sidelines learning the sport. He spent that year reading baseball books and watching games at the Coliseum before making his debut as a sidekick to Rene Cardenas in 1959.

“Jaime has done such a tremendous job because he’s done it basically on his own,’’ Scully says.

Scully had a big role in Jarrin’s development. The Dodgers initially didn’t allow the Spanish-language crew to travel, so Jarrin spent his first eight years announcing the road games from a Pasadena studio while interpreting the action called by Scully and Jerry Doggett.

“Listening and translating from Vin Scully every night, you can’t help but pattern yourself after him,’’ Jarrin says.

With Jarrin’s storytelling and descriptive narration, the Dodgers Latino fan base slowly grew until fully awakening in 1981 with the emergence of a young pitcher who couldn’t speak English.

Valenzuela was the star, and, to the English-speaking world, Jarrin was his voice — sometimes more. On days Valenzuela pitched, Jarrin would leave his broadcast booth after the eighth inning to go downstairs and interpret Valenzuela’s postgame interviews. The pitcher was so shy, Jarrin admits, sometimes he freelanced a little.

“I tried to use all my vocabulary for him, I tried to make him sound better,’’ Jarrin says. “I never changed the essence of his words … I just expanded what he was trying to say.’’

Valenzuela said he knew what Jarrin was doing, and appreciated it.

“I was shy, and maybe he put a little bit extra in there, but that was great,’’ says Valenzuela, now a fellow Dodgers broadcaster. “He always said something great.’’

Between Valenzuela’s starts and interviews, Jarrin would counsel him on how to conduct himself on a national stage, advice for which Valenzuela is grateful.

“He’s helped me out everywhere I go, off the diamond, telling me good things, what I can do, what I should know, helping me out a lot,’’ Valenzuela says. “He’s done so much for baseball and for me.’’

Fernandomania made Jarrin nationally famous, but did not earn him better seats in stadiums or more respect in Midwestern cities that viewed Spanish-language crews as outsiders.

Amid this constant professional fight, Jarrin suffered personal tragedy. In Feburary before the start of the 1988 season, his son Jimmy died suddenly from a brain aneurysm.

The Dodgers won a World Series championship, but Jarrin spent the season in mourning, never missing a game yet barely able to leave his hotel room on the road.

For the next 15 years, he and wife Blanca paid weekly visits to Jimmy’s grave site. Today, the only constant in Jarrin’s ever-changing immaculate wardrobe is the gold chain that hangs around his neck. It belonged to Jimmy.

“His presence is always with me,’’ Jarrin says. “I will never get over it.’’

Two years after his son’s death, Jarrin nearly died as the result of injuries suffered during an auto accident in Vero Beach that left him hospitalized for several months. He returned in the middle of the season but worked in pain throughout the summer.

“But I always worked, because I’ll always understand I am an immigrant, and I feel we have an extra duty to present ourselves with dignity and represent in the right way,’’ Jarrin says.

He and Blanca have been married for 64 years. They have resided in the same San Marino home for 52 years. His broadcast partner on KTNQ 1020 is Jorge, the oldest of their three sons.

Jarrin’s contract expires after this season, and he will probably eventually cut back to a West Coast schedule like the one used by Scully in his final years, but the Dodgers have said he has a job for life.

“He can go as long as he would like,’’ says Lon Rosen, Dodgers vice president and chief marketing officer. “To the Dodger organization and Dodger fans, Jaime is as important as any of our legends. He’s the connection and voice for a large portion of our fan base.’’

The Dodgers are going to throw him a 60th anniversary party this summer. Maybe more than one. They haven’t announced it yet, but they promise it will be huge.

There should be a bobblehead. Maybe one day the Dodgers will even erect a honorary Jaime Jarrin seat in the press box behind home plate to remind everyone of those years when other stadiums stuck him in the outfield.

Se va, se va, se va, despidala con un beso.

Jarrin is not ready to kiss it good-bye. But when he eventually retires, there is one thing he swears will not happen. He says he will not imitate Scully and sing to the crowd. He says he cannot sing.

But if he had to, he says he knows what song would be the soundtrack of his life.

Mi Manera.

Get more of Bill Plaschke’s work and follow him on Twitter @BillPlaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.