‘Mr. Hockey’ Gordie Howe, ‘the best of all time,’ dies at 88

- Share via

Gordie Howe was 44 and had recently retired from the NHL when he was invited to a Kiwanis Great Men of Sports dinner in the Canadian town of Brantford, Canada.

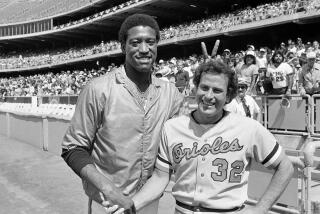

One guest of honor was only 11 years old but was already being touted as a future hockey superstar. Howe, always personable and patient with kids, smiled as he posed with the boy, hooking his stick around the chin and left ear of the slightly embarrassed youngster with the blond bangs.

The kid was Wayne Gretzky, who would go on to break Howe’s NHL record of 1,850 points in 1989. But Howe always maintained a prime place in fans’ hearts long after Gretzky passed his scoring mark.

Howe, known as “Mr. Hockey” for his enduring skills and the fierce competitiveness that inspired him to come out of retirement at 45 to play alongside two of his sons, died Friday, according to the Detroit Red Wings. He was 88.

“Mr Hockey left peacefully, beautifully, and w no regrets,” his son Murray Howe said in a text to the Associated Press.

Howe suffered a massive stroke on Oct. 26, 2014, and had rallied only to be felled by several subsequent strokes that robbed him of his speech and confined him to bed.

A member of hockey’s Hall of Fame and a longtime ambassador for the game, Howe had endured many health problems the last few years, including dementia and spinal surgery.

One of the strongest and most fearless players who ever laced up a pair of hockey skates, Howe played right wing with a blend of talent and toughness that made his name a part of the sport’s jargon. Although he retired for the last time in 1980, before many of today’s players were born, a player who gets a goal, an assist and a fighting penalty in a game is still said to have earned “a Gordie Howe hat trick,” a tribute to Howe’s ability to beat opponents at every facet of the game.

“Gordie’s greatness travels far beyond mere statistics; it echoes in the words of veneration spoken by countless players who joined him in the Hockey Hall of Fame and considered him their hero,” NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman said in a statement. “Gordie’s toughness as a competitor on the ice was equaled only by his humor and humility away from it. No sport could have hoped for a greater, more-beloved ambassador.”

Howe never scored 50 goals in a season and only once exceeded 100 points, but he led the NHL in scoring six times and was voted its most valuable player six times while playing for the Detroit Red Wings, with whom he won four Stanley Cup championships. In 1973, two years after he retired the first time, he joined the upstart World Hockey Assn. and played on the same line with his sons Marty and Mark with the Houston Aeros.

The trio moved on to the New England Whalers, one of four WHA teams absorbed by the NHL. Howe became a grandfather during his final NHL season, 1979-80.

Although Wayne Gretzky scored 894 NHL goals to Howe’s 801, and Gretzky and Mark Messier passed him in points — Gretzky scored 2,857, Messier had 1,887 and Howe had 1,850 — Howe made his mark in a tougher era, when the NHL had merely six teams and had not been diluted by expansion. He holds the NHL record for most games played, 1,767, and also played 419 games in the WHA.

“Just being around him and getting to know him – a 10-year-old child who gets to meet his idol,” Gretzky said Friday of Howe on Canada’s TSN. “As I tell people all the time, he was nicer and better and bigger than I could have ever imagined. From my point of view I picked the right idol. He was the greatest player that ever lived and happened to be maybe the nicest athlete that I’ve ever met.”

He skated one shift for the minor league Detroit Vipers in the 1997-98 season, allowing him to say he’d played in an unprecedented six decades.

“If you’d asked me when I broke into the league if I thought I’d still be playing five decades later, I would have said you were crazy,” he said in his autobiography, “Mr. Hockey: My Story,” which was released in mid-October 2014. “When the Red Wings called me up from their farm club in Omaha in 1946, I just wanted to last the season.”

Bobby Orr, a singular defenseman who was among the most gifted players to grace the ice, told the Detroit Free Press in 2003 that Howe had no peer.

“Remember, he played against all that talent in the Original Six era when they were traveling by train, no charters,” Orr said. “In 1968-69, he had 103 points. It was his best season, and he was 41 years old. In his last year, at age 52, he played all 80 games and scored 15 goals with 26 assists.

“When it comes to who was the best hockey player ever, don’t even go there with me. There is no question that Gordie is the best of all time.”

An animated storyteller who gladly signed autographs for hours, Howe’s spirits sagged after his wife, Colleen, was diagnosed in 2002 with Pick’s disease, a neurological disorder that causes dementia. The couple had met at a bowling alley near the old Detroit Olympia Stadium in 1951 and married in 1953. They had three sons and a daughter.

Colleen Howe, one of the first female sports agents and an advocate for junior hockey in the Detroit area, was her husband’s business advisor and staunchest defender. She died in 2009; he cared for her throughout her final illness.

In the forward to “and ,,, Howe!,” the 1995 authorized biography of Gordie and Colleen Howe, their youngest child, Murray, described a man who “managed to dislodge a few players’ faces from their heads with one hand, while casually scoring with the other,” but also “chased a purse-snatcher on foot, then in a car, then on foot again, until the would-be criminal gave up the goods, in exhaustion.”

Gordon Howe was born March 31, 1928, in the town of Floral in the western Canadian province of Saskatchewan, but the family moved to Saskatoon days later. He was one of 11 children, nine of whom survived infancy. His father had come north from Wisconsin as a homesteader; his mother emigrated from Germany to Canada as a young woman.

Their home had no running water and young Gordie had to carry heavy pails of water uphill, which he said strengthened his legs for hockey. He played before school on frozen rivers and ponds, in temperatures that often sank 35 degrees below zero. He would stick-handle all the while, developing the dexterity that helped him bedevil opponents for decades.

He played on as many as five teams at one time, developing a left-handed shot to go with his natural right-handed shot. He’d often switch hands on his stick while skating to the net, further confusing opposing goalies.

He attended his first NHL camp at 15, in Winnipeg, at the invitation of the New York Rangers. They wanted him to go to boarding school and develop his skills, but he declined. The following year, when a Red Wings scout invited him to camp in Windsor, Canada — and bought him his first suit — Howe agreed and was assigned to a junior team.

He signed his first pro contract in 1945, for $2,350 and a Red Wings jacket that he didn’t get for two years. He made his NHL debut in the 1946-47 season and scored seven goals but began to blossom in 1949-50. Flanking Ted Lindsay and Sid Abel on what was dubbed the “Production Line,” Howe scored 35 goals and 68 points and accumulated 69 penalty minutes.

During that season he suffered the most serious injury of his career. Late in a playoff game against Toronto, Howe went to hit the Maple Leafs’ Teeder Kennedy, but was hit in the eye by Kennedy’s stick and crashed into the boards. He hit his head and lapsed into unconsciousness. Doctors had to drill a hole in his skull to relieve a buildup of fluid on his brain, a delicate procedure.

“As close as I came to shuffling off into the sunset at the tender age of 21, I bounced back relatively quickly from the surgery,” said Howe, who estimated that over the course of his career he took 300 stitches in his face and had his nose broken 14 times. “To this day, I’m still surprised by the speed of my recovery.”

The Red Wings went on to win the Stanley Cup, and Howe returned the next season and helped the Red Wings become a dominant team that won the Cup in 1952, 1954 and 1955. Although the team’s fortunes began to fade — the Red Wings did not win the Cup again until 1997 — Howe finished among the top five scorers for a remarkable 20 straight seasons and averaged 35 goals per season during a time when 20 goals were difficult to achieve.

Arthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome left him in constant pain in his last years in Detroit. He retired in 1971 and was promised a front-office job by the NHL. The role never materialized, and he became unhappy in a meaningless job with the Red Wings.

In an inspired moment, Colleen Howe realized that the new WHA, which was challenging the NHL for supremacy, wasn’t bound by the same rules that prohibited NHL teams from drafting players who were younger than 20. She then engineered the drafting of sons Mark and Marty by the WHA’s Houston Aeros, and Gordie joined them on the ice.

But he wasn’t merely a curiosity: Gordie scored 100 points in the 1973-74 season, third best in the league, and the Aeros won the first of back-to-back titles. “The early years in Houston with Marty and Mark were some of the most fun I’d ever had playing hockey,” Howe said in his autobiography.

When the Aeros’ ownership changed, the Howes moved to Connecticut in 1977 to play for the Whalers. Gordie’s ice time was gradually decreased, leading him to retire in 1980.

Mark, a member of the silver medal-winning 1972 U.S. Olympic team, went on to a successful career with the Philadelphia Flyers. He joined his father in the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2011.

With Colleen’s guidance, Gordie became active as a charity fundraiser and a commercial pitchman.

Marty Howe, who became his father’s business manager after Colleen Howe died, said in his parents’ biography that he never minded being measured against his father.

“You always cope with some negative comments, like, ‘You’ll never be as good as your old man.’ And of course, I never expected to be,” he said. “You get challenged on the ice, you get compared everywhere in your life to Gordie.

“But, I think all of the good points always outweighed the bad. When you know what a good person my dad is, it doesn’t bother you.”

Howe is survived by his sons, Marty, Mark and Murray; his daughter, Cathy Purnell; nine grandchildren, four great-grandchildren and a sister, Helen Cummine.

Twitter: @helenenothelen

MORE SPORTS NEWS

Javier Hernandez and soccer gods benefit Mexico

Duke star Brandon Ingram has pre-draft workout for Lakers

Dodgers select Wisconsin high school shortstop Gavin Lux with first-round pick

UPDATES:

8:29 a.m.: This post has been updated with statements from Murray Howe and Gary Bettman.

This post was originally published at 6:57 a.m.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.