From the archives:: Ali’s last hurrah turns into circus with few laughs

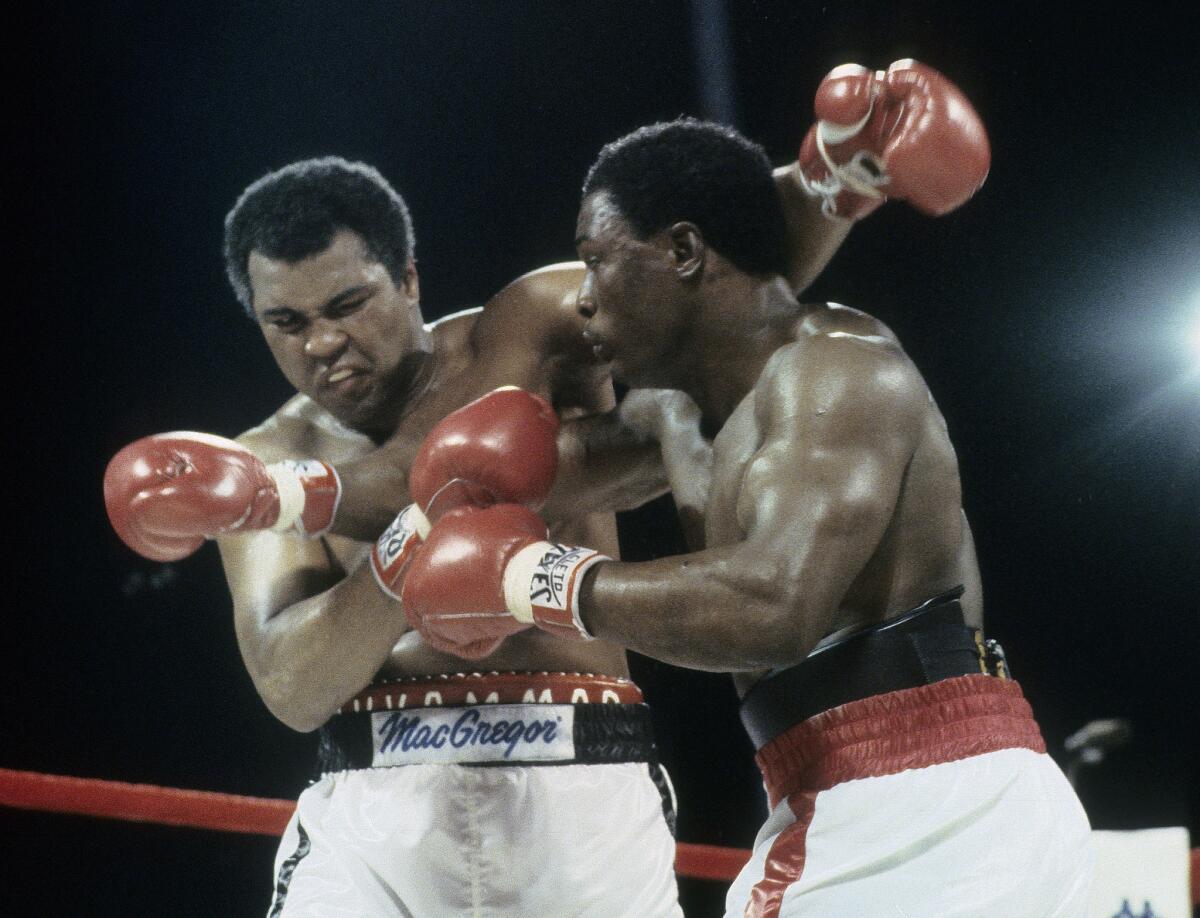

Trevor Berbick, right, throws a punch at Muhammad Ali on Dec. 11, 1981, at Queen Elizabeth Sports Centre in Nassau, Bahamas.

- Share via

Nassau, The Bahamas — Little enough was expected from this evening and little enough was delivered. Muhammad Ali went out to see if he had gotten any younger Friday night and, sure enough, he hadn’t.

Looking all of his 39 years and 48 weeks, he lost a clumsy unanimous decision to the unremarkable Trevor Berbick, though he did manage to finish with his head still on his shoulders.

“I did good,” Ali said later, “for a 40-year-old.”

It was nice he could go out laughing, and appropriate, too, because the promotion had been a farce without peer in the modern era. Even if Ali kept on overreaching himself, he deserved better than this; it was like hearing that Napoleon had finished up fighting winos in the Elba town square, and losing.

Mystery Promoter

Berbick appeared only after getting a guarantee of his purse an hour before the scheduled start of the show. An hour later, when the first bout was to begin, it was learned that only two sets of gloves had been provided for the entire card. Jay Edson, a judge, warned trainers not to cut the laces at the end of any of the fights.

There was no bell, so a cowbell was borrowed from the TV truck. From the same truck came a stopwatch and a whistle to sound the 10-second warning. There were only two dressing rooms, so everyone dressed together. Scott LeDoux, fighting on the undercard, said he felt like Kirk Douglas in the gladiator scene in “Spartacus.”

LeDoux’s fight against Greg Page was supposed to be for the United States Boxing Assn. heavyweight title, but the promoters forgot to call the USBA and get its sanction, so it became a non-title fight.

“I’ve never seen a promotion this bad,” Page said. “Not as an amateur. Not as a pro. Not as a tourist.”

The promotion was led by the mysterious James F. Cornelius, nicknamed Sunny Jim by the press, which he alternately snarled at and stonewalled. He was described in his press kit as an Atlanta businessman, though he was later said to be from Los Angeles. He was also said to be a Black Muslim and a neighbor of Ali’s.

“He’s a promoter,” Ali’s manager, Herbert Muhammad, told the New York Times’ Dave Anderson. “He promotes something.”

He didn’t promote much here, except confusion. It was against that backdrop that Ali, barred from fighting by the U.S. commissions, began his latest comeback, figuring, obviously, that he could stay close to Berbick and then think of something.

But he couldn’t even stay close. Judge Alonzo Butler had it 97-94, and the other two judges, Clyde Gray and Edson, had it 99-94. Ali had a moment or two, when he cuffed Berbick with a punch that had little menace in it, causing Cornelius to jump to his feet, cheering. Cornelius had a contract to promote an Ali-Mike Weaver title fight, which mercifully will have to be deferred.

“Age is slipping up on me,” Ali said later. “He was too strong. I could feel his youth. Weak … weak … reflexes … timing.”

That Ali even climbed into the ring Friday night represented one of the great miracles of his long career. First of all, he was, in only the most rudimentary sense, in any kind of condition. His workout sessions ran 20 minutes or less and his morning run wouldn’t have tested your grandmother. Members of the British press volunteered to run with him one day and watched Ali run 50 yards, walk three miles and then get picked up by a limo.

Fat, middle-aged and all, Ali was in a lot better shape than the promotion was. The people running this thing were first-timers, short of cash and totally disorganized. Thursday’s weigh-in, for example, had to be held up while someone went for a scale. There were several hundred members of the media clustering around, and the promoters announced that everyone was going to have to show credentials. Of course, no credentials had yet been issued. The promoters repeated that ID was going to be required. So the reporters held up their Master Charge, Visa cards, cigarettes, whatever.

Crisis Press Conferences

The promotion had worse troubles. Berbick decided he wanted the same guarantee that everyone else on the card seemed to have. He had received $100,000, he said, but he wanted a letter of credit for the balance — thought to be another $150,000 — or he wasn’t fighting.

Friday afternoon was given over to crisis press conferences. Cornelius was supposed to arrive momentarily. The promotion’s boxing consultant, Booker Griffin, a Los Angeles publisher of a boxing news letter, came down at 4:16 to stall for time, which he readily admitted.

“The party line,” announced Griffin, “would be to say that they’re not here because traffic is too heavy, but I have too much respect for your intelligence to tell you that.

“Our people must come up with a document that satisfies Trevor Berbick.…”

Someone asked what the hard part was.

“It has to be backed by collateral,” Griffin said.

That means money, folks. Griffin was asked if his employers had any money. “I can’t answer that,” he said. He also told the assembled press, “I hope you remember that I’m just a functionary.”

At that stage, Cornelius was wandering around in the lobby by himself, which suggests that events were well out of his hands. At 5:21, Berbick’s trainer, Lee Black, came downstairs and announced that the TV people had given them the necessary letter of credit, drawn on Barclay’s Bank, and the fight was on.

“No sweat,” said Cornelius, as he rode down in a hotel elevator. He stepped out into the lobby and a friend embraced him, as if he’d just won the war. Everyone went off to the magnificent fight site to see what could go wrong next.

At this point, the shortage of gloves, bells and stopwatches was discovered, but the show stumbled onward, finally reaching the main event. Ali came out somber, paying attention, trying to fight. He didn’t clown and he didn’t run. But from the beginning, Berbick kept rushing him and overpowering him. Ali is still good enough that he could make Berbick miss most of the time, but it was still the younger man’s fight.

“I was trying to hit him on the chin and put him out of his misery,” Berbick said. “I made the fight. If it wasn’t for me, there wouldn’t have been a fight. It would have been a waltz.”

Ali finished the evening uncut and unmarked, though his face was a little swollen. He wasn’t sure, he said, but right now he didn’t think he was going to fight anymore.

“My wife thinks I did good, though,” Ali said.

Why not? He’d made another $1.5 million, and he was still wearing his head, and maybe, just maybe, this was finally the end.

Note: This article was originally published on Dec. 12, 1981.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.