Lance Armstrong’s lies carry a steep, and rising, price

- Share via

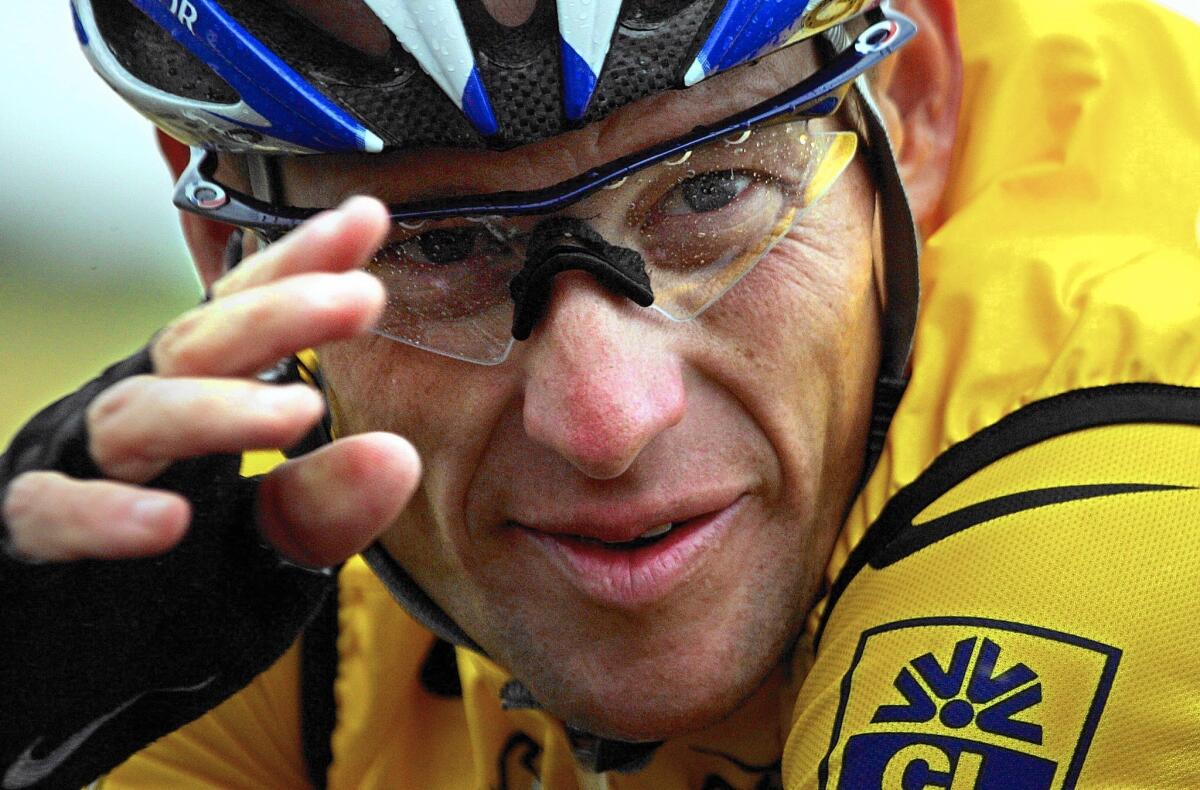

Not long after Lance Armstrong’s unprecedented seven Tour de France titles were stripped in 2012, the cyclist tweeted a defiant photo.

Armstrong reclined on a couch in a dimly lighted room, appearing unworried about the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency’s exhaustive report that accused him of cheating by taking performance-enhancing drugs to fuel his history-making feats. The framed yellow jerseys from his Tour de France wins hung on the wall behind him.

The message was clear: The punishment didn’t faze Armstrong.

Now, though, his sins carry a steep price. This week, an arbitration tribunal ordered Armstrong to repay Dallas-based SCA Promotions Inc. $10 million because of the cyclist’s years of deception. SCA underwrote bonuses promised to Armstrong by Tailwind Sports Inc., his management firm.

“For a long period of time, I think that athletes didn’t feel that there were any consequences to lying about the use of performance-enhancing drugs,” said Jeffrey Tillotson, SCA’s attorney.

Tillotson said the decision will change that. “There are so many financial relationships intertwined with these athletes that I think it will make them more careful,” he said.

The ruling’s target was a man who once seemed to transcend sports.

Doctors gave Armstrong a 40% chance to survive testicular cancer. He beat the disease and went on to front the Livestrong charity with the ubiquitous yellow bracelets as he dominated the Tour de France and built an empire of sponsors. In the process, Armstrong became a touchstone for what is possible in the face of long odds.

None of that mattered in the ruling.

“The case … presents an unparalleled pageant of international perjury, fraud and conspiracy,” the decision said. “It is almost certainly the most devious sustained deception ever perpetrated in world sporting history.”

Timothy Herman, Armstrong’s attorney, called the award “unprecedented” and expressed confidence that Texas state courts would take their side.

Courts rarely overturn arbitration decisions, said Michael McCann, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and sports law expert.

That would be the latest in a string of setbacks for Armstrong.

In 2013, he admitted to Oprah Winfrey during a teary interview that he used the drugs during all of his Tour de France wins. Within a day, all of his sponsors fled. Armstrong estimated the loss at $75 million.

But his trademark intransigence remained. In an interview with Dan Patrick last year, Armstrong, who has been banned from professional cycling for life, said he still considered himself a seven-time Tour de France champion.

“A lot of people in this position have become inoculated to the consequences,” said Maurice Schweitzer, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School whose research includes ethical decision-making and deception. “They’ve become less concerned about losing it all. They’re used to having people handle things.”

SCA, which paid Armstrong bonuses for winning the Tour de France in 2002 and 2003, held off on a $5-million payment for his 2004 title because of persistent rumors that Armstrong used performance-enhancing drugs.

Before the arbitration panel ruled on the dispute, the parties struck a deal they called “fully and forever binding” that awarded Armstrong $7.5 million. In keeping with his long-standing denials, Armstrong testified that he didn’t use drugs.

“Lance was defiant,” said SCA attorney Tillotson, who twice questioned the cyclist under oath. “It was, ‘I don’t use drugs and I’m going to sue you if you say I do.’ There was a vengeance about it.”

Armstrong’s claims of innocence unraveled in October 2012 when the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, helped by information provided by SCA, revealed in a report that included more than 1,000 pages of evidence that Armstrong’s titles were aided by performance-enhancing drugs.

“This boundary-pushing is part of what makes them great,” said Shawn Klein, a professor at Rockford University in Illinois who runs the Sports Ethicist blog. “This same attitude, this trait of pushing to the limits, is also what leads some to use PEDs. It’s another way to keep pushing.”

SCA sued Armstrong in 2013 and the arbitration proceeding reconvened.

“Perjury must never be profitable,” said the decision by the tribunal that voted 2 to 1 in favor of SCA. It went on to excoriate Armstrong’s side, saying perjury was committed “with respect to every issue in the case” and witnesses were “intimidated and pressured … to lie.”

The decision, Tillotson said, is the toughest he’s seen against an individual.

“They said, ‘You didn’t care, you still don’t care and we think you’re still lying now,’” he said.

Tillotson expects Armstrong, whose net worth was estimated at $125 million before the lifetime ban, to challenge the decision. Still he gave the cyclist’s representatives instructions on how to wire transfer $10 million in case they wanted to concede. That isn’t likely.

Armstrong’s problems are only beginning. SCA is pursuing in Texas state court another $5 million in claims against Armstrong for fraud.

And in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., the Justice Department joined former teammate Floyd Landis’ long-standing whistleblower lawsuit against Armstrong under the False Claims Act in 2013. In a letter to Atty. Gen. Eric Holder the same year, U.S. Anti-Doping Agency Chief Executive Travis Tygart expressed frustration that the “massive economic fraud” and “cold, calculated lies” extended beyond the organization’s ability to punish.

The case, which claims that Armstrong cheated the U.S. government because the U.S. Postal Service sponsored his team, is ongoing. If Armstrong loses, damages could reach tens of millions of dollars.

“He still, to my read, seems relatively unwilling to accept the full responsibility of what he’s done,” deception researcher Schweitzer said. “He seems to blame the situation and the environment, as if he doesn’t bear full responsibility for the choices that he made.”

Twitter: @nathanfenno

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.