Column: Gary Bettman doesn’t care if fans hate him. Why his NHL reign has lasted 30 years

- Share via

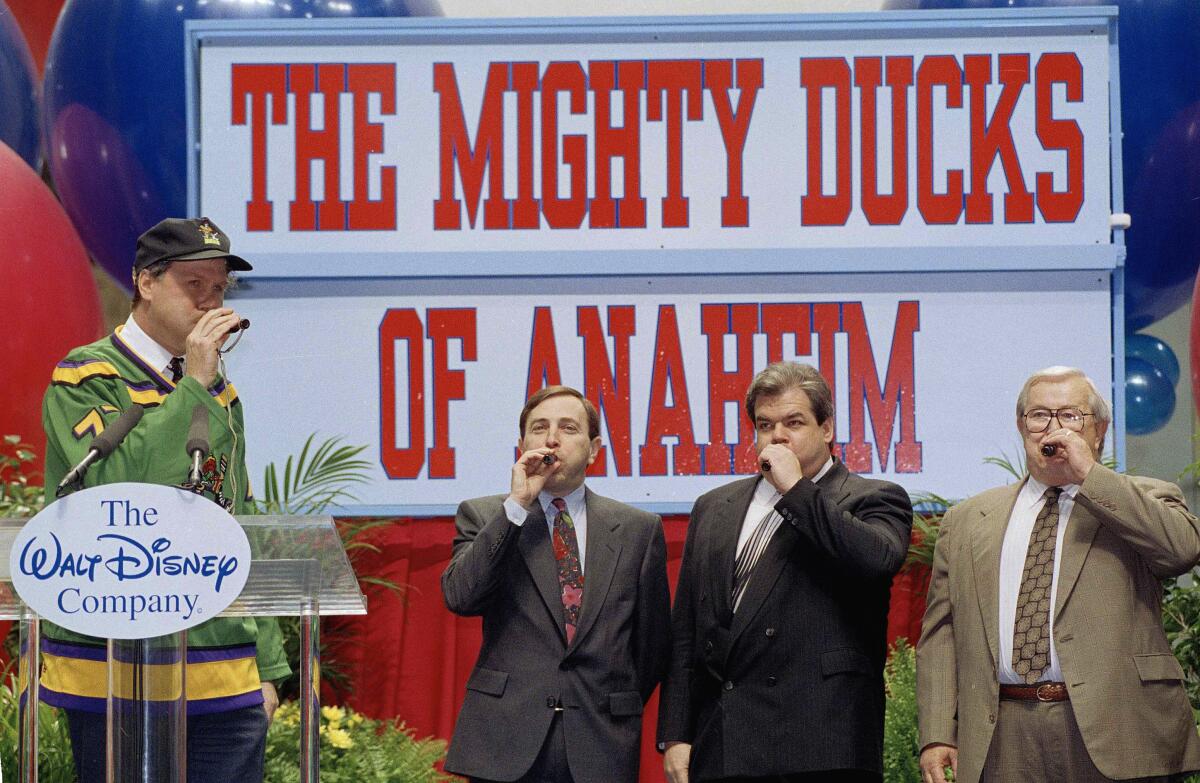

Gary Bettman made a name for himself in the 1980s as the NBA’s general counsel and third-in-command, the sharp, young lawyer who created the league’s salary cap. Working alongside Commissioner David Stern, Bettman helped stabilize the NBA and transform it into a star-centric league watched by a global audience.

Still, it was a surprise when the NHL, seeking a chief executive who could get them a salary cap and revenue boost, landed on Bettman. He wasn’t born into hockey or part of its old boys’ network. He was from Queens, N.Y., not Canada.

“When I first heard about it, I sent the guy a puck and I heard he spent all day at his desk trying to figure out how to open it up,” said Pat Williams, then general manager of the NBA’s Orlando Magic.

American skier Mikaela Shiffrin breaks Lindsey Vonn’s record for World Cup Alpine victories, cementing her place among the greats in her sport.

Bettman isn’t warm and fuzzy. He can be haughty, alienating the fans whose interests he claimed to be protecting when he locked players out three times during labor disputes.

Spots of color flame in his cheeks when he stubbornly defends what seems indefensible, such as his contortions to keep the Coyotes in Arizona at a tiny college rink and being unmoved by studies that have found links between repeated head trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease found in autopsies of more than a dozen NHL players.

Yet Bettman is smart. Very smart. He figured out how to open that puck and stretch the reach of a sport that doesn’t translate well to TV and has little tradition in many areas of the U.S. The longest-serving commissioner in the four major North American sports leagues, Bettman on Wednesday will celebrate 30 years on the job. He turned 70 last summer but has no retirement plans.

“Like birthdays, it’s just a number,” Bettman said. “Because everybody’s having me do it, I do reflect on the fact that I’ve been at this a while, and I continue to be excited and energized by what I do.”

His tenure has been marked by a mixed bag of innovations. Remember the Fox glow puck? He also agreed to TV contracts with obscure networks before the current profitable deal with ESPN and Turner. He hit on a winner with outdoor games that appeal to nostalgia. He wisely copied the NBA’s draft lottery and fan-friendly All-Star weekend and was an early adapter to social media and digital technology. During his watch the NHL adopted shootouts and three-on-three play in overtime during the regular season, adding drama but distorting the standings. Many Canadians despise him for Americanizing their game, but he devised a program to aid Canada-based teams when currency disparities handicapped them.

League revenues, about $400 million when he began, were around $5.3 billion last season. Digital advertising boards introduced this season will pad revenues, although those ads are distracting when they change. Franchise values have soared: Philip Anschutz and Ed Roski paid $113.25 million for the Kings in 1995, and Forbes valued the franchise at $1.3 billion last year. Vegas paid $500 million to join the NHL in 2017. A Seattle group paid $650 million in 2021 to become the league’s 32nd team, but additional expansion is on hold.

Growth is Bettman’s hallmark. So is confrontation.

Media interest sparked by the New York Rangers’ 1994 Stanley Cup triumph faded when he locked players out a few months later and lost nearly half the season without getting the salary cap owners wanted. He canceled the entire 2004-05 season to get a hard cap but the resulting revenue split didn’t satisfy owners — so he imposed another lockout before the 2012-13 season and got players to reduce their cut of hockey-related revenues from 57% to 50%.

He allowed players to represent their homelands in five Olympics but kept them home from Pyeongchang in 2018 and Beijing last year. In the first instance, he didn’t want to cede control to the International Olympic Committee and International Ice Hockey Federation; he used the potential 2022 Olympic break to make up games lost to COVID. Players wanted to go both times. There’s no plan in place for the 2026 Milano-Cortina Games.

“I think he’s done a great job for his constituency, which is the owners. I think he’s done a great disservice to the game of hockey,” said Allan Walsh, co-managing director of hockey at the Octagon agency and Bettman’s chief critic.

“I don’t believe he’s grown the game to its fullest potential and has made several decisions along the way that are highly questionable. I don’t believe he’s been good for the game and I don’t believe he’s had the best interests of the game at heart for a very long time.”

Walsh contends a soft salary cap, luxury tax and meaningful revenue sharing would have left NHL teams “in a much healthier position and have much higher revenues than where we are at.” Bettman said a soft cap would have widened the gap between large- and small-market teams, making a hard cap essential for survival.

“Unfortunately, we had no choice based on the circumstances that we found ourselves in and based on what we sought to achieve, it took a full season to persuade the players’ association as to what we needed to do to move the game forward,” Bettman said. “And if you look at the results subsequent to us having that collective bargaining agreement and the system that’s in place, a combination of salary cap and revenue sharing, the results are clear. And I don’t think we would have gotten to this point without that system. In fact, it’s not that I don’t think — I’m certain of it.”

Much of his job consists of putting out fires, and he has two significant problems on the horizon. In May, the city of Tempe, Ariz., will hold a referendum on a new arena for the Coyotes, who moved to a 5,000-seat arena on Arizona State’s campus after the city of Glendale refused to renew their lease. They’ve gone through multiple owners but Bettman is banking on them thriving in Tempe. “I view it now as an opportunity,” he said. “That’s the exact right location.”

Bobby Hull’s shooting prowess, skating skill and overall team leadership led to 604 career goals and a Stanley Cup for the Chicago Blackhawks.

More immediate is the looming bankruptcy of Diamond Sports Group, which operates the Bally Sports regional broadcast networks. The Kings and Ducks are among 12 NHL teams whose games could be disrupted. “We’re mindful of what’s going on and we’re strategizing as to what may happen under various contingencies,” Bettman said.

As his momentous anniversary approached, Bettman was reluctant to say how he’d hope to be judged. “I want people to think of me, particularly my family and friends, as somebody who’s been a good person,” said Bettman, father of three and grandfather of seven with his wife, Shelli. “The league is not about me. I have had the honor of being a part of this game in important ways, but other people will define my legacy. Some people will think I did a good job and some people will think I didn’t.”

He did open that puck, though.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.