- Share via

The legend began in Ohio youth leagues at the local park, the first iteration of the St. Vincent-St. Mary state-championship “Fab Five” taking shape in the Akron chill.

There was a 6-year-old on his and LeBron James’ team one year, Willie McGee remembered. The kid only played in blowouts. Hadn’t scored all year. A “mascot,” McGee called him.

But in one of the last games of the season, a young James drove middle. Rolled the ball across the court, one destination in mind. And the kid picked it up, flung it with all his might, and scored his first bucket.

“It was like, ‘Man,’” McGee said, “‘only LeBron could make that pass.’”

Only LeBron. That passing, the ability to elevate those around him, was his greatest strength from a young age. McGee will tell you. So will Dru Joyce III, or Romeo Travis or Brandon Weems, the kids that went from playing on youth courts to winning three state championships at St. Vincent-St. Mary.

LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony and other celebrities showed up to watch Sierra Canyon hold off New York’s Christ the King 62-51 on Monday in Chatsworth.

“They tried to recreate it with different players at different times,” said Travis, now an assistant coach at SVSM. “But there could never be another LeBron James.”

“Except,” Travis continued, “he made his own clone.”

Fair or not, the question has followed Bronny James ever since he enrolled as a freshman at Chatsworth Sierra Canyon, already one of the most star-studded high school basketball programs in the nation. Ever since, the world got a glimpse of his talent with a 15-point effort that year to beat James’ alma mater St. Vincent-St. Mary in Columbus, Ohio.

Who will the next James be?

On Saturday, he returns to Columbus for a game against SVSM as a highly touted senior prospect. And 20 years after playing their final season, those Fighting Irish greats will have a chance to see Bronny in the same position as they knew his dad — the most famous high school basketball player in the nation selling out an Ohio gym.

“It’s surreal, to be honest with you … I just can’t really describe it because I know where we come from, and how hard LeBron had to work to get to where he is,” said Weems, now the assistant general manager of the Cleveland Cavaliers.

LeBron James and those early-2000s SVSM teams have kept in touch, and have had conversations about fatherhood, McGee said. Specifically, letting their kids choose what they wanted to be in life. Letting them be their own men.

But by nature and talent, Bronny’s path has veered close to James’ at the same age.

“It’s pretty cool that [Bronny’s] been able to experience some of the things that I was able to experience,” James told The Los Angeles Times on Tuesday. “But at the end of the day, he’s creating his own path and creating his own legacy.”

And to the men who knew LeBron James’ path better than anyone, who’ve seen his legacy grow since those early days in Akron, both those statements are true. Because LeBron James’ former teammates see unique differences in the similarities.

One kid combined dominant size and athleticism with a natural feel for the game. One kid combines a prolific shot and handle with a natural feel for the game.

Those St. Vincent-St. Mary teams hopped off the bus, confidence bursting out of their Adidas jerseys, because they knew they had the best player on the floor every time out, Travis said. They had the trump card. The ace. The 6-foot-7, 225-pound steamroller with all-time athleticism and a pro’s vision.

“It’s like taking the test when you know you got all the answers,” Travis said.

LeBron James was dominant in transition. A playmaker on defense. A superior passer and finisher. His perhaps lone weakness as a prep prospect? Shot selection, according to Travis.

“He felt like he had to prove that he could shoot jumpers,” Travis said. “So sometimes he bailed the defense out with tough jumpers, just to say that he could shoot.”

And Bronny, James’ former teammates said, is without a doubt the better shooter at this stage.

At 6-3, Bronny doesn’t have his dad’s size. His bounce is startling, his hang time noteworthy, but not as awe-inducing as James’. But he shares much of his father’s IQ, Weems said.

“He sees things that other players may not see, and that’s a gift LeBron had,” Weems said.

LeBron James was the undisputed top prospect in the country. Bronny isn’t at that level, even though he’s ranked as high as sixth in ESPN’s 2023 California rankings. But he’s talented enough, Weems feels, to play in the NBA — whether it’s after a freshman year of college hoops or multiple seasons.

“He’s going to continue to grow and get more athletic,” Weems said, now in his seventh year with the Cavaliers. “So I believe that other front offices feel the same way.”

Basketball, for those St. Vincent-St. Mary teams, McGee said, was entertainment. But it was also a meal ticket. They had a collective goal of getting to college, of a free education, of helping their families. And at the center of it was LeBron James, always looking out for everyone else.

“He understood, even at an early age, that he had some God-given talents and some gifts,” Joyce III said. “And in large part, a lot of it was to change the outcome of his surroundings. To make life easier on his mom and his family.”

“It’s pretty cool that [Bronny’s] been able to experience some of the things that I was able to experience. But at the end of the day, he’s creating his own path and creating his own legacy.”

— LeBron James

But during the few times LeBron James struggled, it went largely unnoticed. When St. Vincent-St. Mary lost in the state championship game in his junior year to Roger Bacon High, it wasn’t widely treated as the end of the world, Travis remembered.

“I would have to say there’s more pressure on Bronny than there was LeBron,” Travis said. “Just because of the social media presence — how your failures would be so public.”

Bronny, now, has 6.8 million Instagram followers, more than Jeff Bezos and Tiger Woods. Every lowlight brings crowing from comments. Every highlight too.

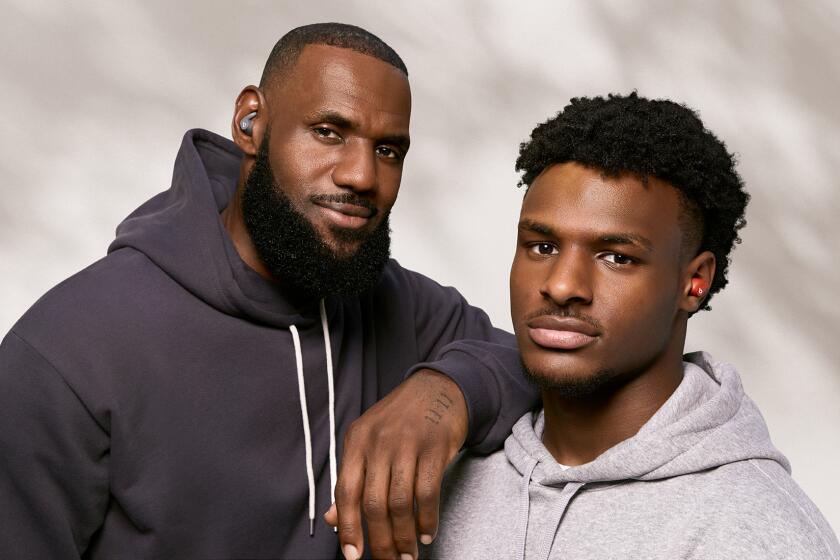

A week after Nike announced it had inked Bronny James to an NIL deal, Beats by Dre announced it signed the son of Lakers star LeBron James.

“I couldn’t begin to understand what it’s like to be the sibling, the son, of an all-time great,” said Dru Joyce II, who coached LeBron James at St. Vincent-St. Mary and still remains there. “Trying to follow in his footsteps and have to deal with all the comparisons, the talk.”

The possibilities for Bronny, James’ former teammates said, are endless. But as of now, he’s chosen basketball. And stepping into a larger offensive role his senior year, he’s led the Trailblazers to a 7-1 record this season entering Saturday.

“This may be a temporary thing,” McGee said. “This may not be his everything … I think he’s gon’ be a DI athlete, he’s gon’ play professionally, but is that what he wants to do? Is that what he want to do forever?”

You don’t get this far, achieve this high of a status in high school hoops, though — no matter your last name — if you don’t love the game, McGee said. And Bronny, while quiet on the floor, plays with unbridled joy: the pull-up threes, the roaring dunks.

Bronny wears No. 0 in honor of his favorite player, Russell Westbrook, ESPN reported during the broadcast of Monday’s game against Christ the King. Not his father’s No. 6, or No. 23.

“He wants to create his own lane — I think he’s done a great job with that,” Travis said of Bronny. “... Most people either love him or hate him. And I’m just grateful that he’s been able to withstand all that negativity and become his own man.”

There will never be another LeBron James, McGee said. Never another kid who could make that pass in that youth-league game. Never another kid who could replay his story.

“But [Bronny],” McGee said, “can be the best person he can be.”

Times staff writer Dan Woike contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.