Column: Carlos Correa is a Met, and risk management is for every other team

- Share via

There is nothing stopping a team from signing a player with a medical issue. There is nothing stopping Steve Cohen, the owner of the New York Mets.

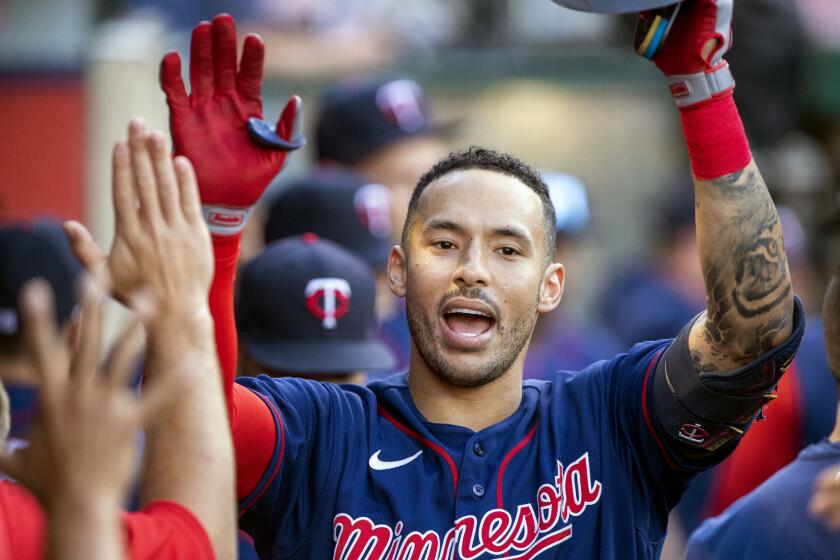

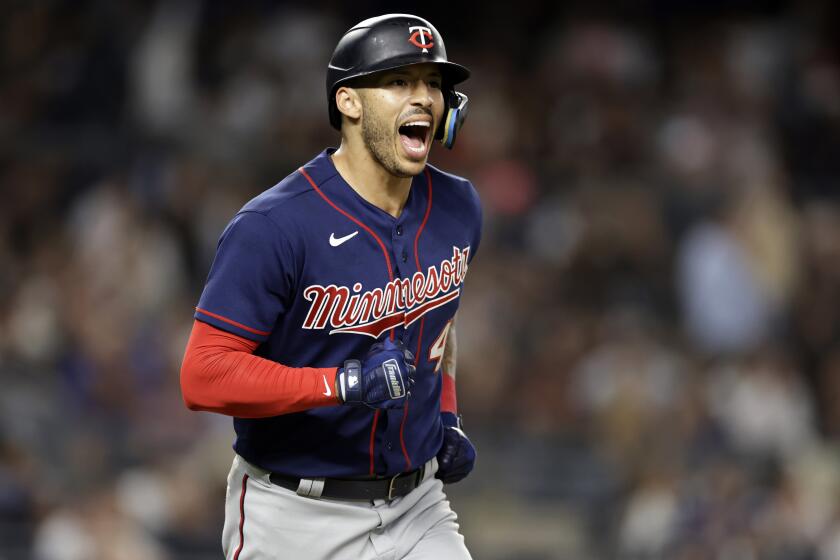

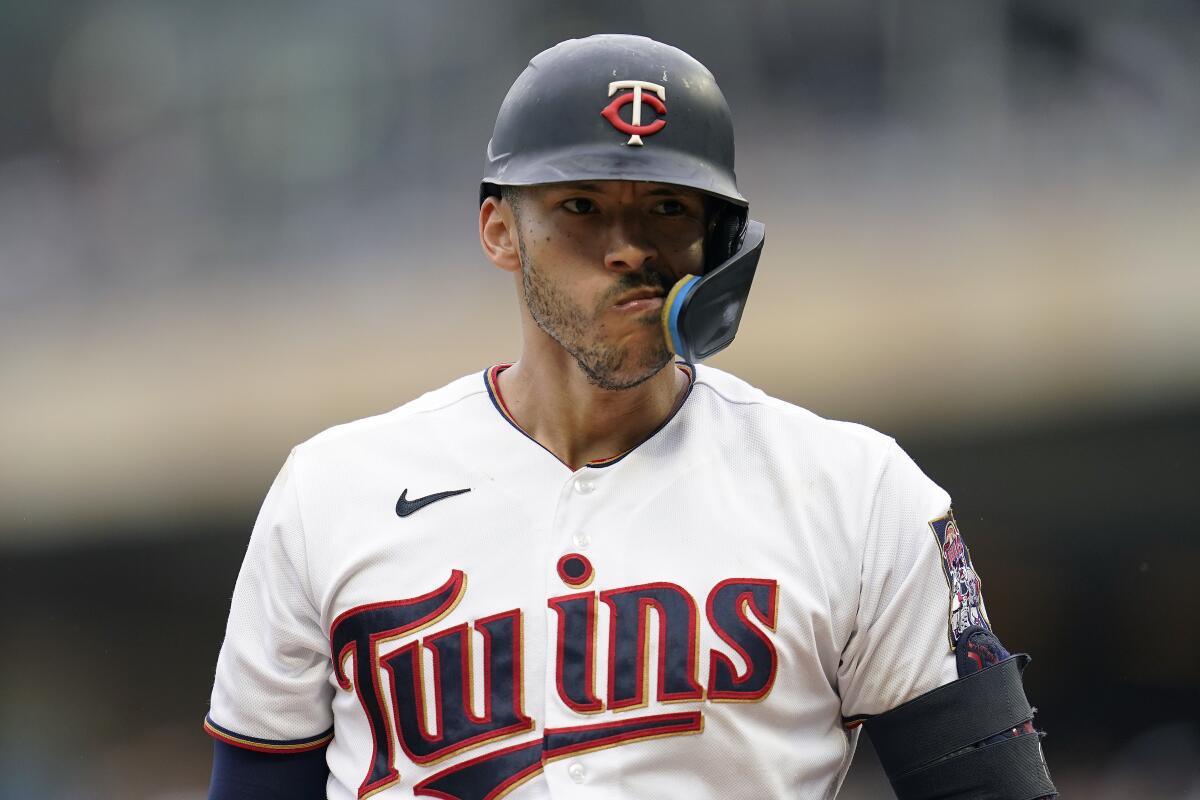

The two converged at midnight. On Tuesday morning, the San Francisco Giants had scheduled a news conference to welcome Carlos Correa. By Wednesday morning, after the Giants hesitated in the wake of Correa’s physical examination, Cohen had swooped in and whisked Correa off to the Mets.

The phrase “agreement pending a physical examination” does not mean a deal is automatically blown up if a player fails the examination. What happened overnight simply means Cohen was willing to take a risk that the Giants and their owners were not.

In this era of evolving analytics and exploding salaries, it is not just sheer dollars that makes Cohen an outlier among baseball owners. It is, interestingly enough, a guy who made his fortune in hedge funds deciding that spending and winning are greater priorities than risk management.

In a statement Wednesday, Giants president Farhan Zaidi said “there was a difference of opinion over the results of Carlos’ physical examination.” Zaidi did not elaborate.

Carlos Correa has agreed to a $315-million, 12-year contract with the New York Mets after his deal with the San Francisco Giants fell apart.

In 2016, Zaidi was general manager of the Dodgers when they signed pitcher Kenta Maeda, despite medical records that Maeda and team officials acknowledged had showed “irregularities.” Maeda and the Dodgers agreed to a contract that would minimize the risk to the team in case of a serious injury but would compensate him handsomely if he remained healthy and effective.

The contract covered eight years, with $3 million in guaranteed salary each year. The total guarantee was $25 million, with incentives that could increase the value of the deal beyond $100 million. In his first year with the Dodgers, Maeda led the team in innings pitched and turned a $3-million guarantee into $12 million in compensation.

He made $33 million in four years with the Dodgers, after which he was traded to the Minnesota Twins. He underwent Tommy John surgery last year.

In 2006, the Dodgers signed pitcher Jason Schmidt for three years and $47 million, despite knowing he had a torn rotator cuff. He won three games in those three years, largely because he required surgery to repair a torn labrum in his shoulder.

The Dodgers sued the company that had insured Schmidt’s contract, alleging failure to pay $9 million in claims. The company said rotator cuff issues were an agreed-upon preexisting condition and cited medical records that the rotator cuff also was repaired during the surgery, although the Dodgers said the torn labrum was the reason for the surgery and in itself would have rendered Schmidt unfit to compete.

The Dodgers and the insurance company reached a settlement, court records show. The terms were not disclosed.

The Giants came up empty on Carlos Correa. But Mets owner Steve Cohen is proving to be the ultimate disruptor, which might not bode well for the Dodgers.

Scott Boras, the agent for Correa, told the San Francisco Chronicle that the Giants indicated they wanted to continue discussions after the medical issue arose but said he “never heard from them after that.” He did not need to engage the Giants again, not with Cohen offering $315 million.

Maybe the Mets’ physical examination will turn up an issue, too. Maybe not. Cohen might not care.

Maybe the Mets will have a difficult time insuring Correa’s contract. Maybe not. Cohen might not care.

The Mets were not without risk even after they landed Correa. Justin Verlander turns 40 next year, Max Scherzer 39. The Mets’ postseason lasted three games this year and could last no longer next year, if Father Time catches up to the aces.

But, in a winter in which Cohen is spending more than $800 million on free agents, a red flag is no reason to slow down.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.