Column: When Scully is telling a story, it’s only fair that the baseballs head foul

- Share via

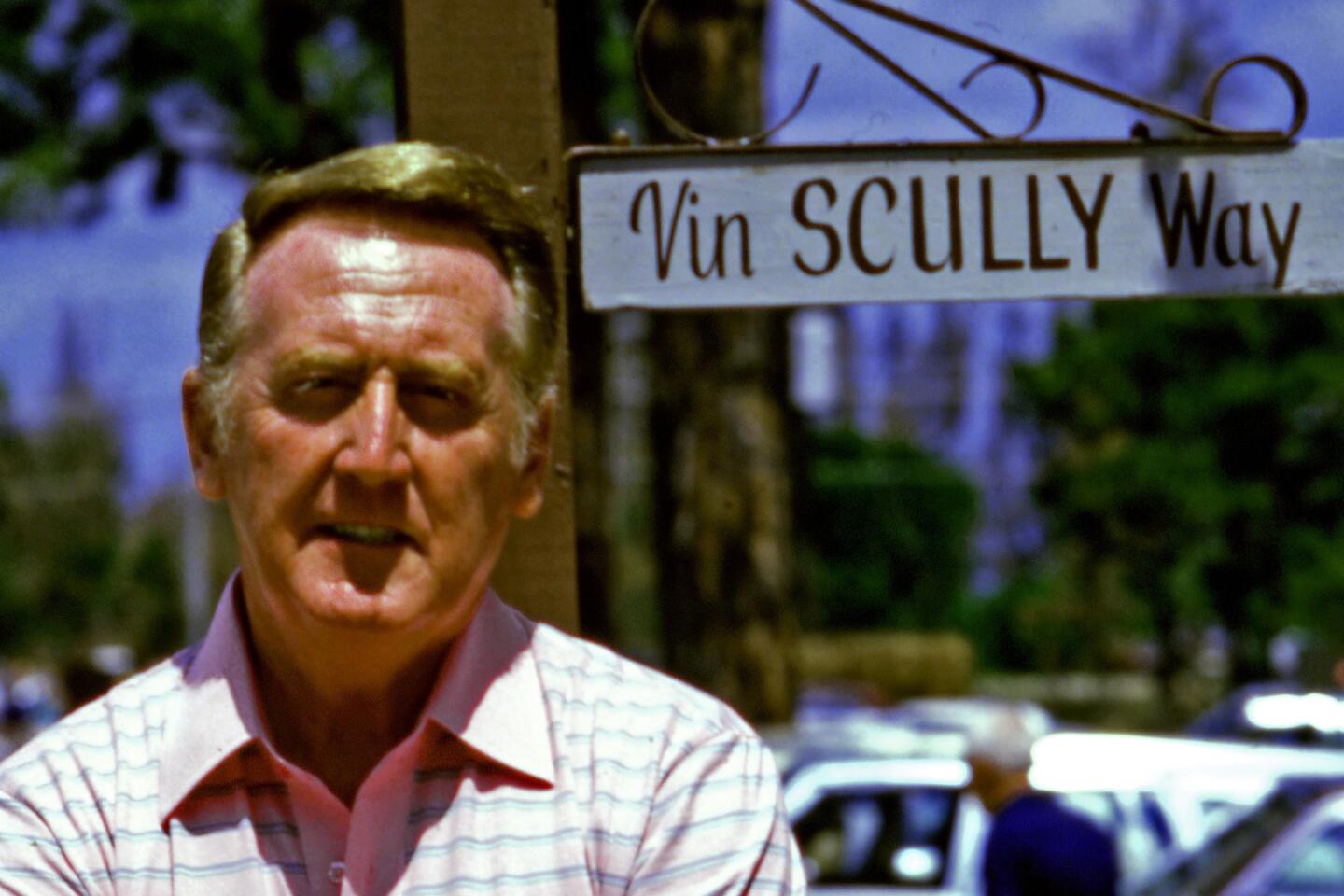

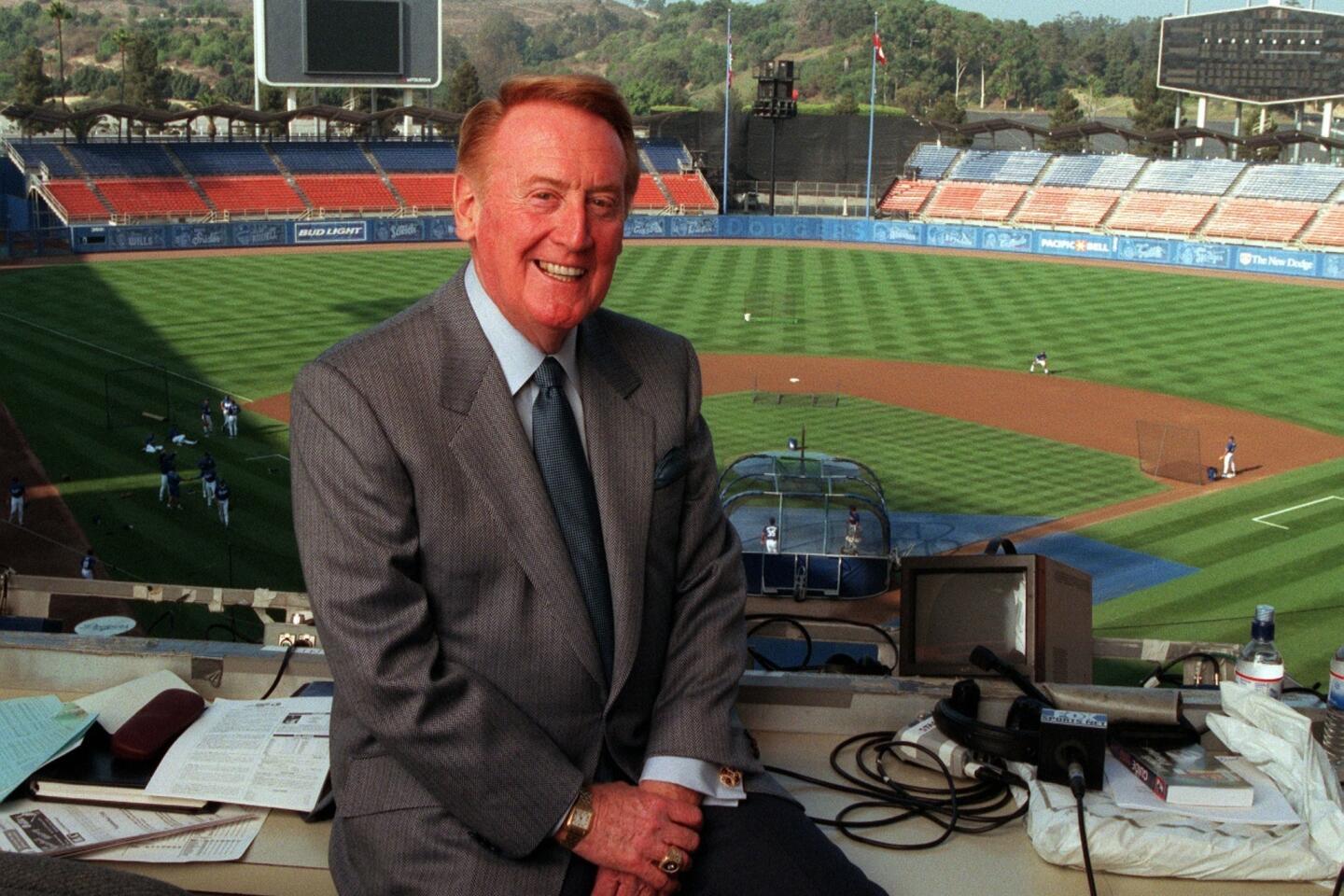

It has been the most compelling part of every Dodgers game for the past 67 years.

A batter will step out of the box to adjust his gloves. The pitcher will step down from the mound to rub the ball. The umpire will take off his mask to wipe his brow. And then, like a sprinkling of glitter across a landscape of drudgery, it fills the screen and the radio and the heart.

Vin Scully will tell a story.

It might be about Pee Wee Reese from 50 years ago, or Clayton Kershaw from last month. It might be bout the origins of home plate, or the history of the glove.

Or it might not be a baseball story at all.

It could be a history lesson about D-Day, or a treatise on the legend of beards. There have been poems about children, and sagas about bird poop.

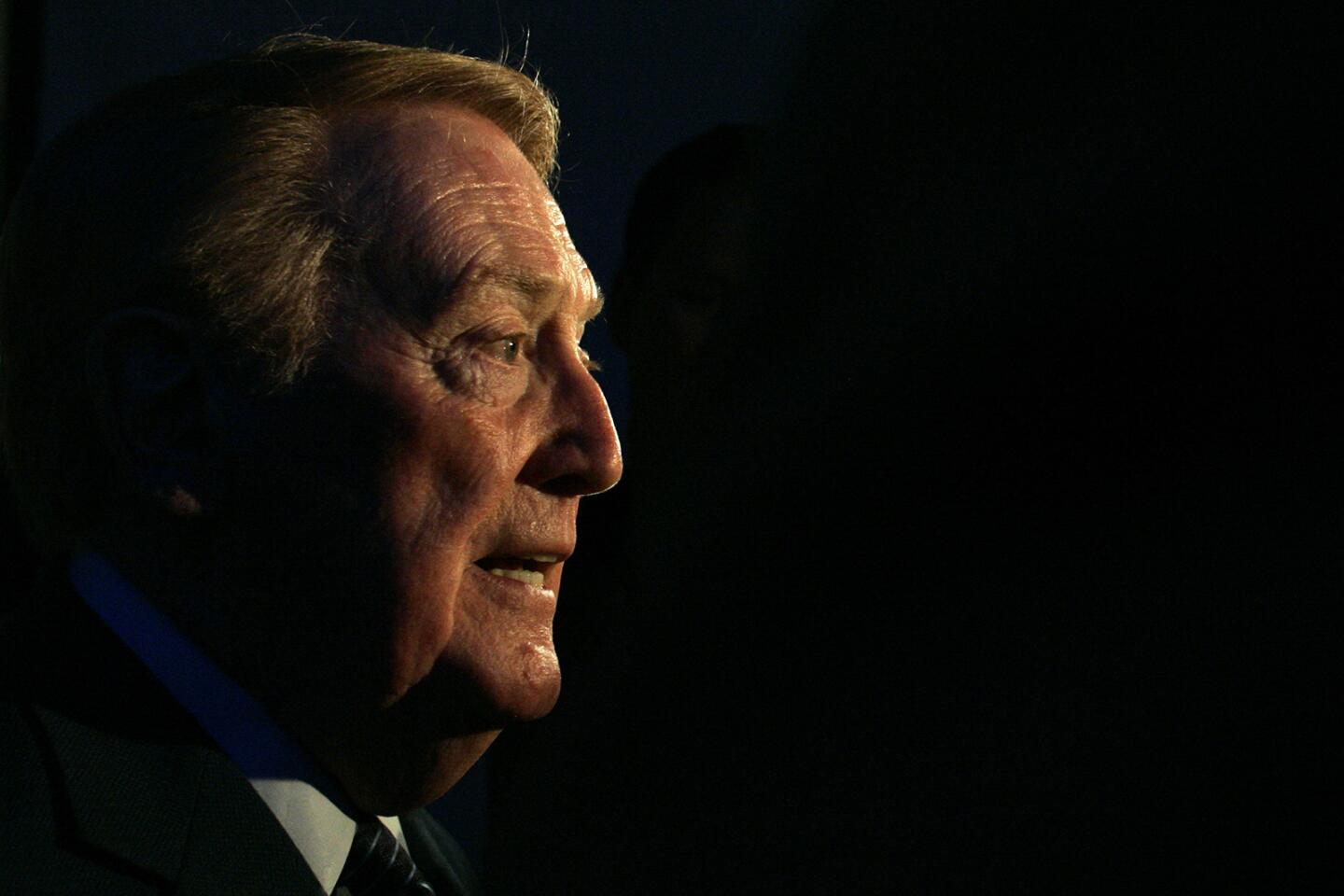

The beauty of the stories is not only in their substance but in their delivery, Scully weaving them seamlessly into his call of the action, pausing only to note a certain pitch or hit, sometimes completely ignoring a play to finish the thought, the stories becoming the game and the game becoming the interruption.

The stories are often better than the game, so good that the Dodgers have the only baseball fans in America who actually cheer for foul balls. That way, Scully has more time to finish.

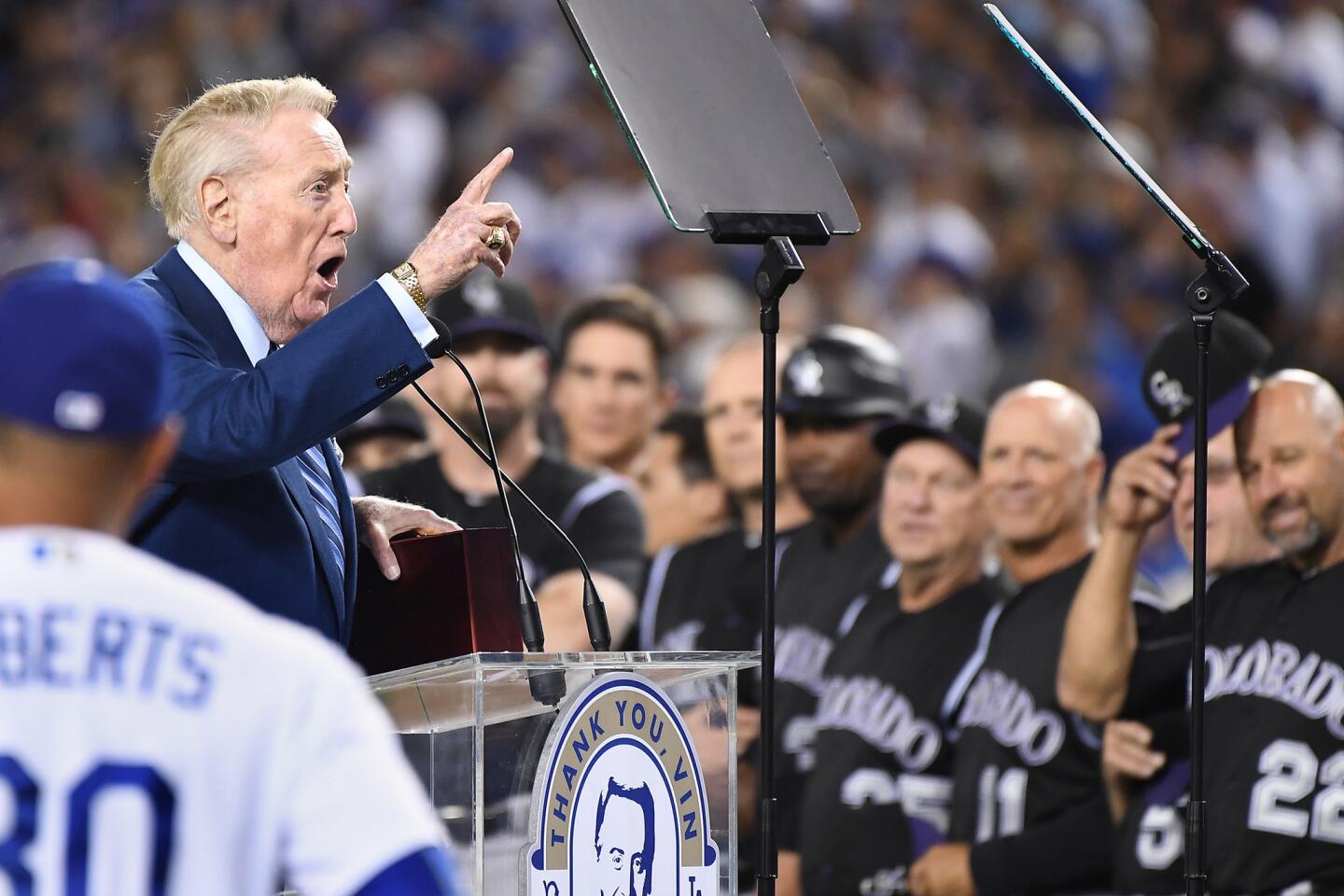

Fans, Scully is right there with you.

“I love foul balls,’’ he said recently. “When I’m telling a story, I hate to get in the middle and have to stop it.”

Does it sometimes seem as though the better the story, the more fouls are hit? Does it seem as though Scully is never cut short?

“I don’t know why it works my way, but it does,’’ he said. “God is very good. It’s like he’s hitting those foul balls for me.”

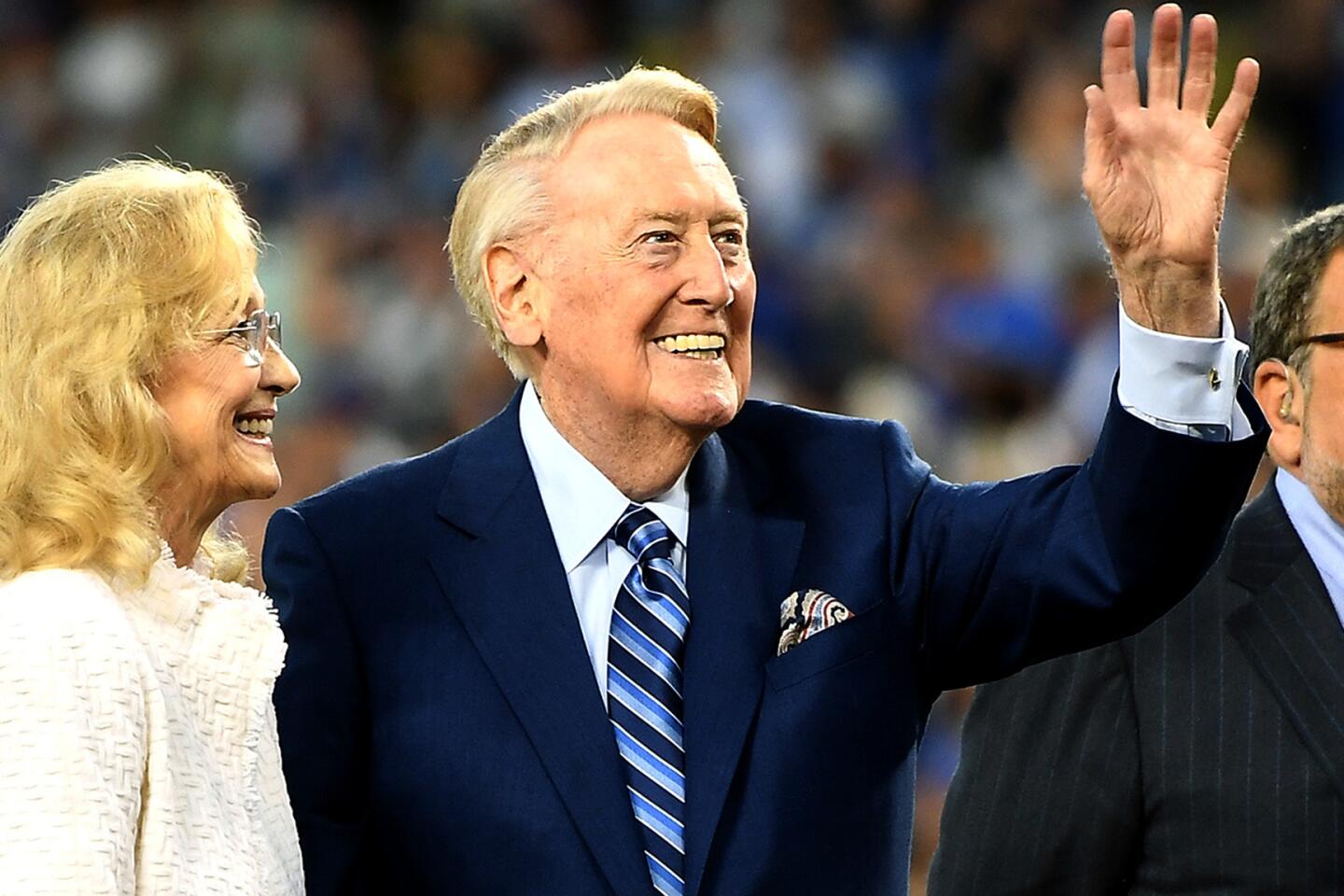

At his core, Scully is the bard of Los Angeles, as much storyteller as announcer, as much bleacher companion as the best broadcaster in history.

Just listen.

“Did I ever tell you about the time Jackie and I raced each other on ice skates? (That’s gonna be hit into right field, Ethier on the run, picks it off, one away. Conor Gillaspie out to right, Barry Zito coming up.) What happened was Rachel and Jackie and I were going up to a resort in the Catskill Mountains a long, long time ago. … Being a kid from the East, I had ice skates. … Now Jackie is putting his skates on alongside of me in the dressing room. … and he says, ‘When we get out there I’d like to race you.’ And I said, ‘Jack, I didn’t know you ice-skated. … (Squirts down to Gordon, two outs.) … Anyway, I said, ‘I didn’t know you ice-skated’ and Jackie says, ‘I’ve never been on skates on my life. … I want to race you because that’s how I’m going to learn.’ … There aren’t very many people who can say, ‘Oh sure, I raced Jackie Robinson … on ice.’”

The game, from several years ago, is a faded memory, but the story is legend. Scully never actually said who won the race, but his stories are never about the destination, always about the journey.

“People have referred to it as like listening to their grandfather telling a story,” said Scully, 88, laughing. “That might be correct, given my age.”

Scully said his style stems from acting as if he’s a guy sitting in the bleachers describing the game to a companion. He said he tells the stories because, well, between innings at a baseball game, isn’t that what everyone does?

“If I was sitting next to a person at a ballgame, it’s the end of an inning, teams changing sides, it’s normal for me to say something, and that might have nothing to do with baseball,” he said. “I guess it’s kind of a running commentary with an imaginary friend.”

And who exactly is that friend? Scully said it could be anybody and everybody, his theory on storytelling cutting to the roots of what has made him such a beloved announcer.

“I’ve never tried to envision that person, I just feel there is someone sitting alongside of me, at the ballpark. I’m talking to the person next to me, we’re both looking at the game,” Scully said. “I don’t have to really describe the game for him, I’m just sitting next to someone, I don’t know who it is, we’re just watching the game. I’ll make a comment, or I’ll imagine sometimes he’ll be asking me a question.”

If you listen closely, you realize Scully doesn’t really do play-by-play announcing. He does play-story-play announcing. He doesn’t really broadcast a game as much as share it.

““Sometimes I’m talking to a fan about some knowledgeable part of the game,” he said. “Another time, I’m talking to a woman, making a comment about a lady’s dress. Sometimes I may be talking to a little child, trying to imagine what that child is saying.”

Sometimes, in all his humble brilliance, Scully even becomes that child.

“We once had a shot of a baby who was yawning,” he recalled. “I started to be the baby, saying, ‘Oh, mom is so warm and soft and the game is OK but perhaps it’s better if I stay here with her.’”

At times when he educates, he reaches back to a bit of personal history, from when he was a child watching his beloved New York Giants.

“One of the first lessons I ever learned in baseball, I was a child in the bleachers in the old Polo Grounds in New York. I’m at least 450 feet from home plate. I noticed that when the batter hit the ball, I would see the ball come into center field, then I would hear a crack,” he remembered. “It puzzled me why I would see the ball for so long, then hear the crack.”

Scully said he turned to another fan for the answer.

“I asked a gentleman and he said, simply, ‘You just learned your first lesson of physics, because the speed of sound is slower than the speed of light,’” Scully recalled.

For 67 years, Scully has been that gentleman sitting in the next seat, talking to the child that was once him.

“When I’m telling the history stories on the air, I’m thinking of when I was that little boy in the bleachers,” he said.

Announcers don’t pay much attention to little boys in the bleachers anymore, perhaps because there aren’t as many little boys in those bleachers. Baseball has an aging demographic, and many broadcasters don’t feel a need to educate or enlighten. Instead of talking with us, they talk at us. It is reasonable to fear that when Scully leaves the booth for the final time, the art of baseball storytelling will retire with him.

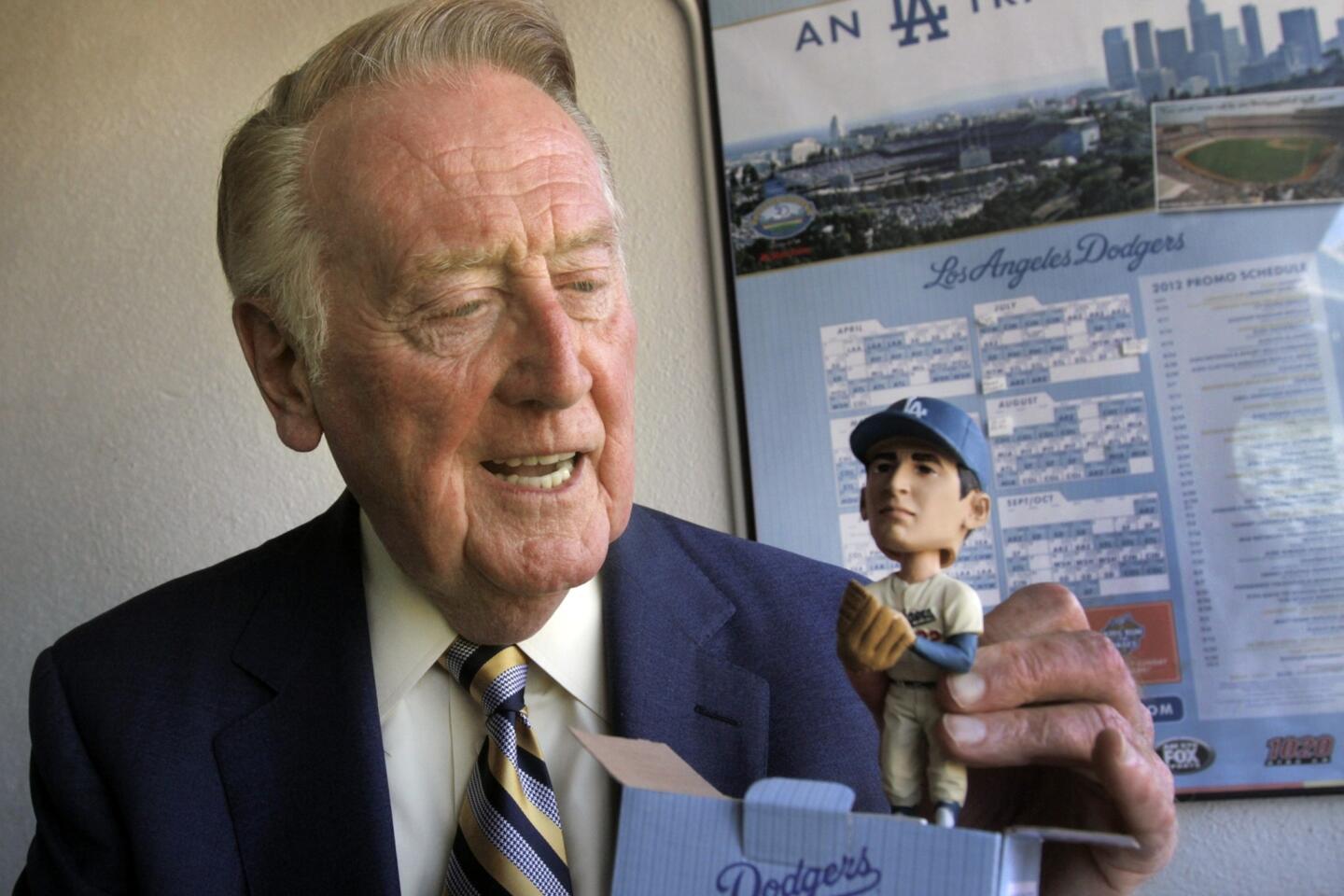

The Dodgers will be a vastly different viewing and listening experience without Scully for reasons that have nothing to do with the baseball. There will be a break in the action and we won’t move to the edge of our seats. There will be a child spotted in the stands and we won’t turn up the volume. When we see someone wearing a cabbage leaf under his cap on a hot day, we’ll have to turn to Google.

The saddest of it being, a player will hit a foul ball and we won’t even care.

Bill Plaschke discusses the magic of Vin Scully’s words and silence after Kirk Gibson hit a home run in the World Series.

Twitter: @BillPlaschke

ALSO

Dodgers fans vote on Scully’s top calls

Plaschke: Vin Scully is a voice for the ages

Three calls that are arguably Vin Scully’s all-time best

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.