From the Archives: The greatest Dodger of them all never wore the uniform

- Share via

Now that it’s the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Dodgers, a few of the savants were sitting around trying to decide who was the most valuable Dodger in the history of the franchise.

That’s easy.

The most artful Dodger of them all never hit a homer with the bases full, stole home in a pennant race, struck out the side with the tying run on third or got Willie Mays to pop up with the game or the championship on the line.

In fact, the most valuable individual never played an inning, made out a lineup, moved an infield in, picked up a ground ball, laid down a bunt or stole a base.

He never made an error, either.

He’s left-handed, reads lips. You can count on him for 150-160 impeccable games a year. He always shows up ready for the game, never hits the disabled list. He’s a manager’s wish, an owner’s dream.

I would say, offhand, the only one who comes close is Jackie Robinson. Robinson’s contributions, too, were more than just on the ballfield.

But when you look down the all-time roster and see the glorious names of Dazzy Vance, Sandy Koufax, Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Don Drysdale, Maury Wills, Don Newcombe, Max Carey or Van Lingle Mungo, you figure some guy poring through the rubble of an archeological dig one day will not have even heard of my candidate. His lifetime average isn’t in there -- but he was a .400 hitter, all right, and he had an awesome assortment of pitches.

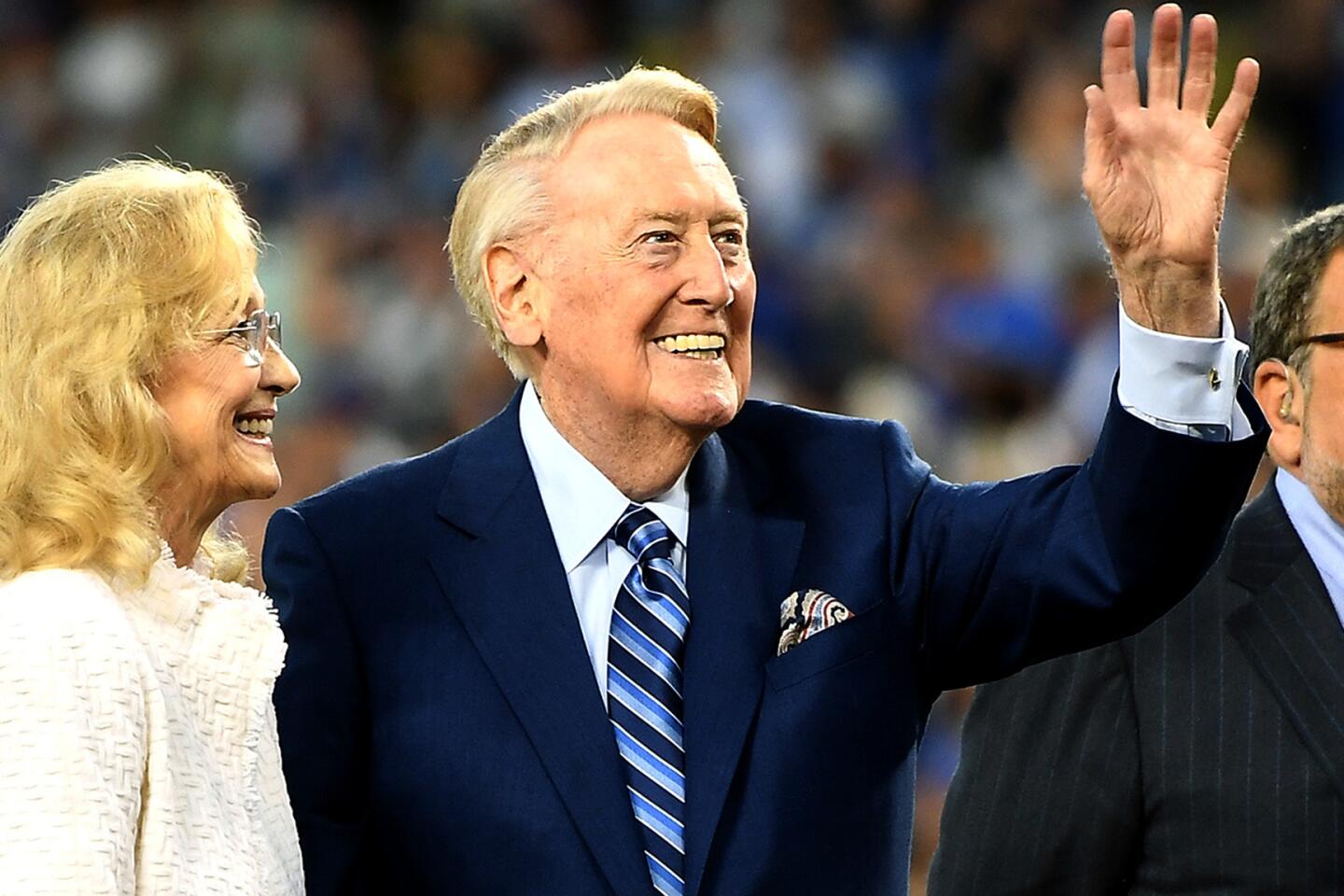

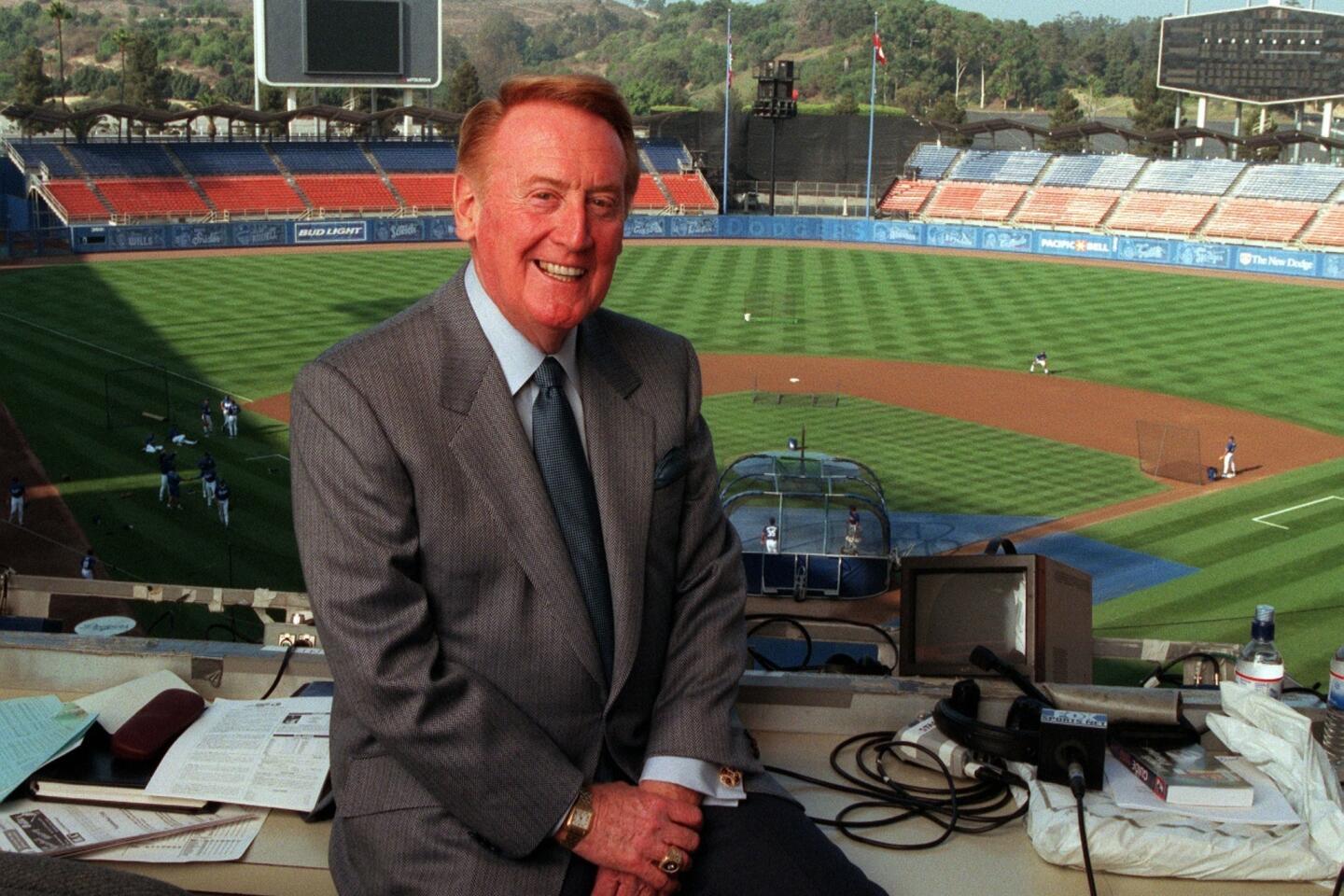

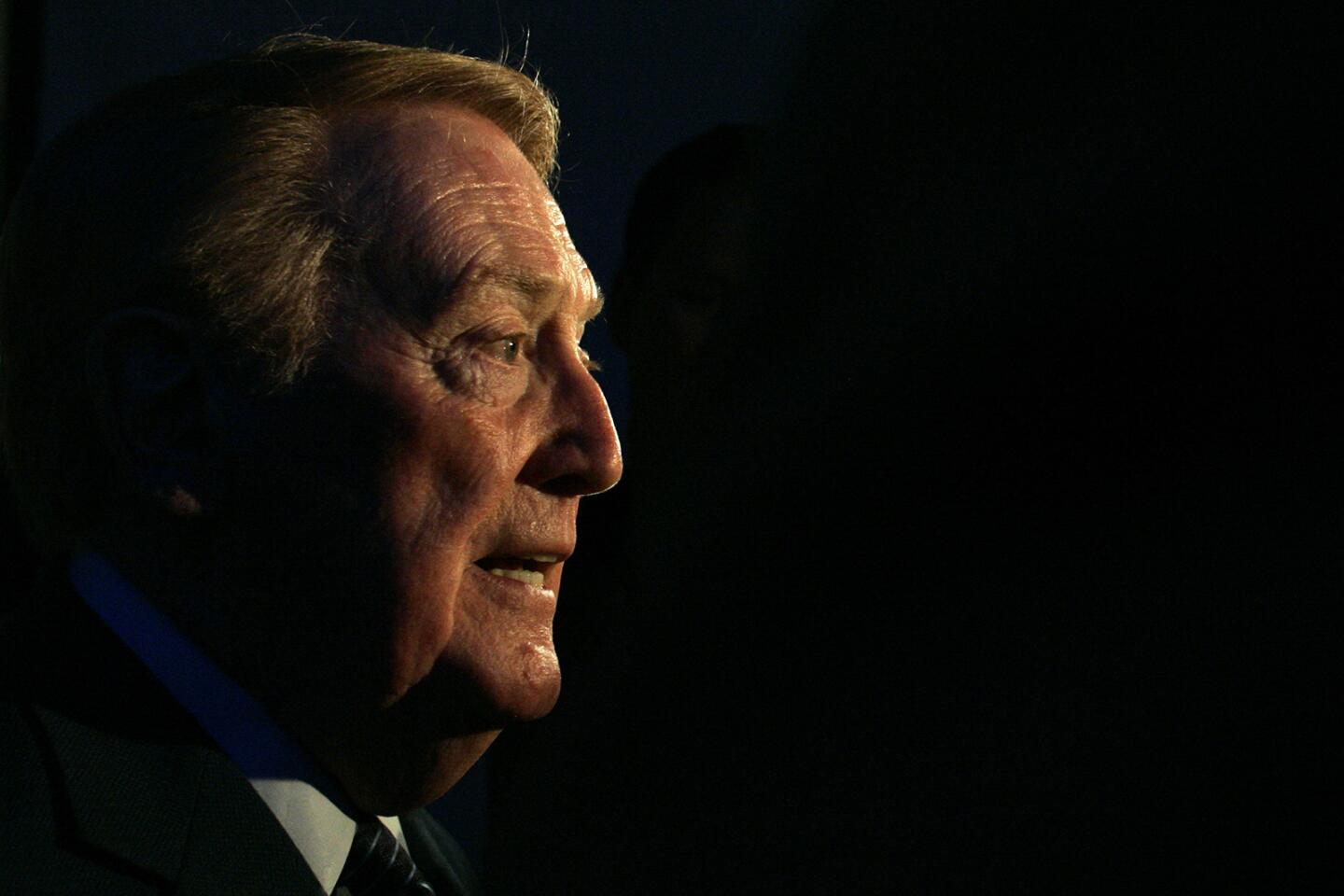

Vincent Edward Scully meant as much or more to the Dodgers than any .300 hitter they ever signed, any 20-game winner they ever fielded. True, he didn’t limp to home plate and hit the home run that turned a season into a miracle -- but he knew what to do with it so it would echo through the ages.

It’s impossible to overestimate Scully’s value to the Dodgers. His mellifluous tone, wafting over the evening air in a ballpark because every transistor in the stadium is tuned to it, has made baseball a field of dreams for three generations of fans. Once, an umpire named Beans Reardon barked at an impatient manager, chafing because the ump waffled over a decision: “It ain’t nuthin’ till I say what it is!” In a sense, 35 years of Dodger fans could say: It ain’t nuthin’ till Scully tells us.

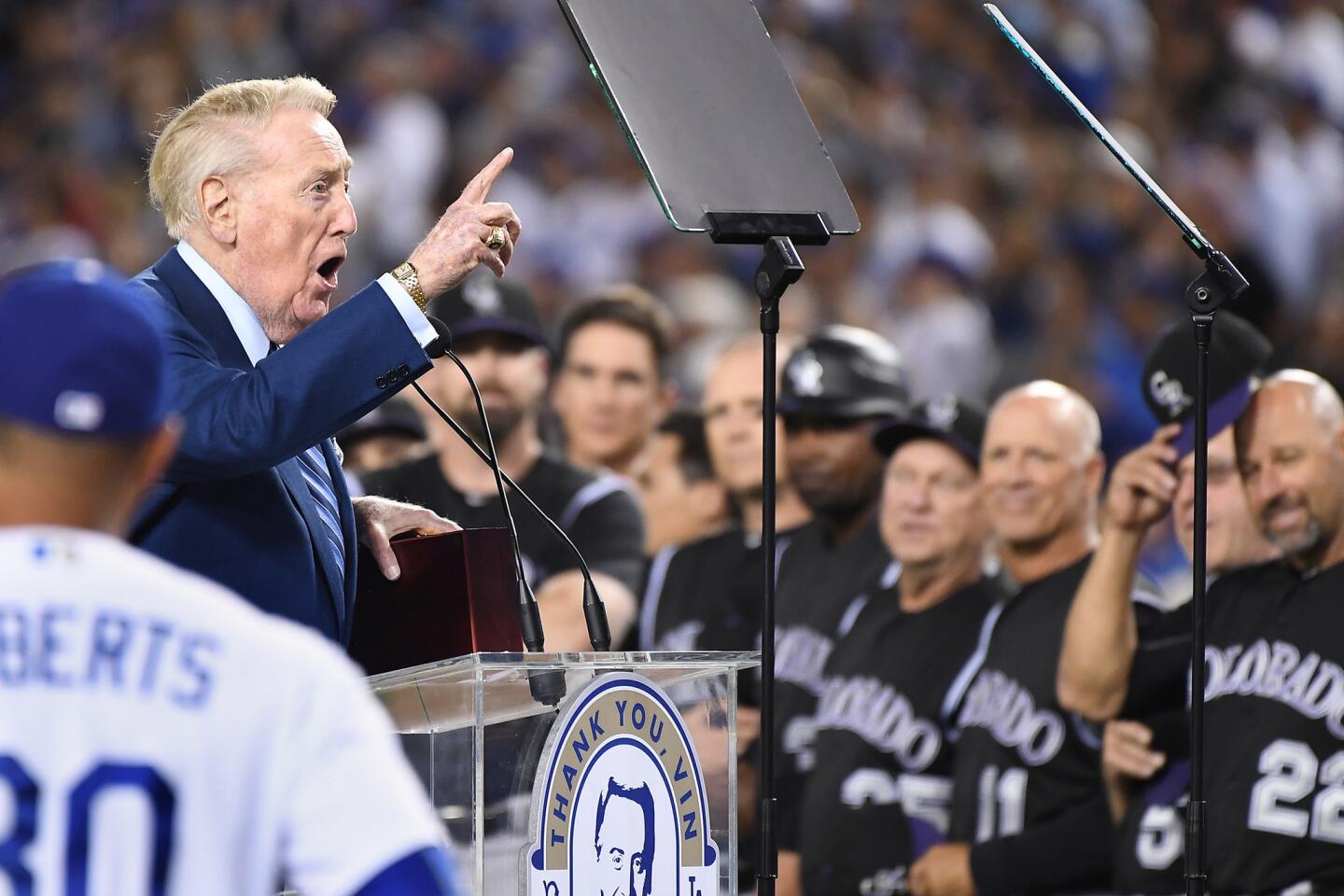

Scully made an art out of baseball broadcasting. He also made journalism out of it. In a profession so full of “homers” — not the four-base kind, the kind where the guy in the booth root-root-roots for the home team -- Scully distanced himself from partisanship. In 1959, in a surprised moment as the Dodgers won a pennant on a throwing error, Scully blurted, “We go to Chicago!” It became an L.A. catch-phrase but, so far as is known, it is the only time Scully used the pronoun we instead of the Dodgers on the air.

He leveled with the fans. They could trust Scully. “It’s playable!” he would assure them of a long, high drive that some shriller denizens of the broadcast booth might want to milk for some suspense.

It was a masterful job of self-control because Scully was as closely identified with the fortunes of the Dodgers as any manager, player or owner they ever had. Scully really told it like it is -- always.

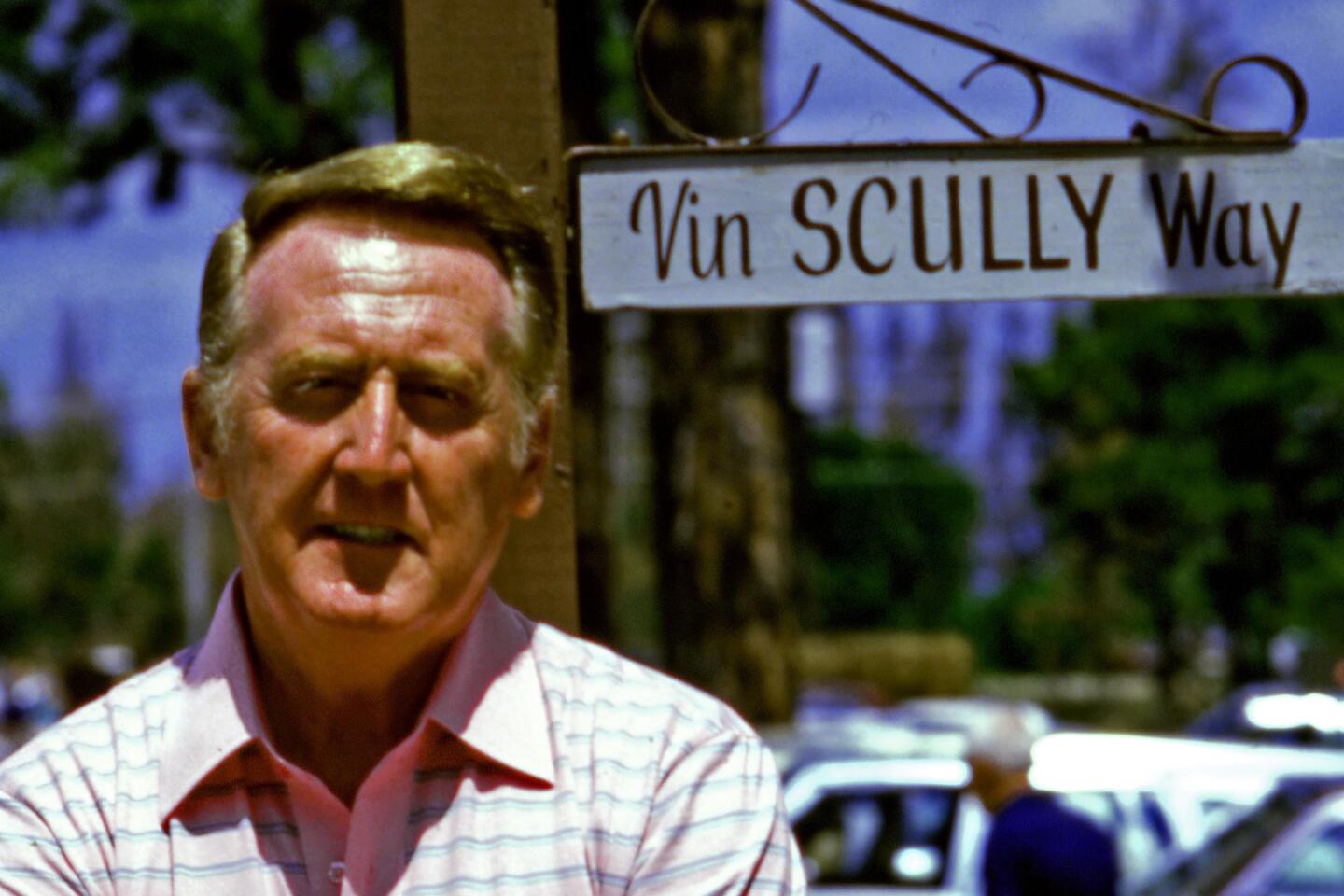

It’s not possible to overstate what Scully meant to the franchise shift to L.A. Here was this team, in the mold of carpetbaggers, pulling into a strange town 3,000 miles from their home base and trying to blend in. Scully midwifed this delicate process.

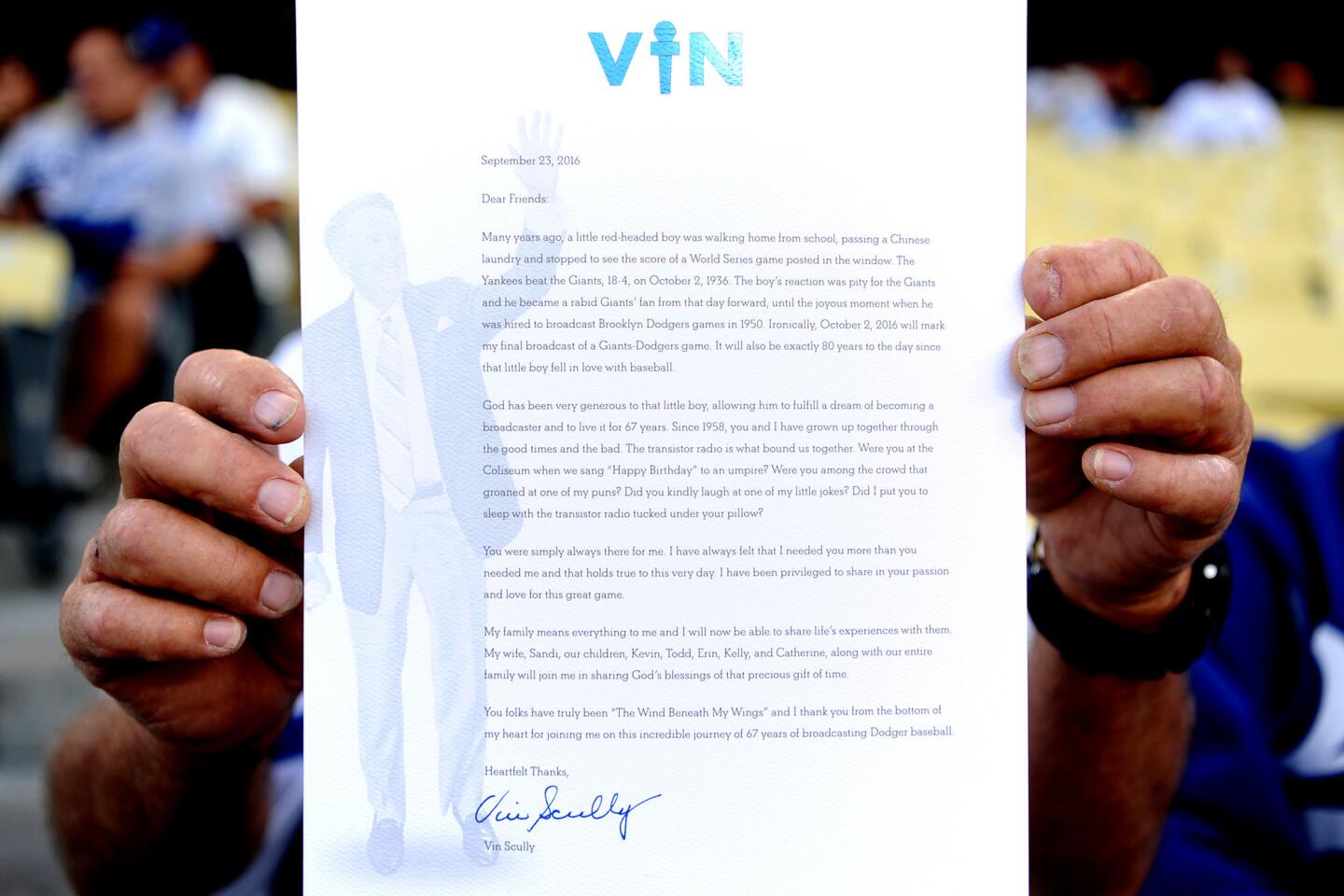

It wasn’t that he didn’t love the Dodgers. It was just that he loved the game. “I remember when I first got the job,” Scully says. “I was just a kid, a street kid. And here I was broadcasting the Brooklyn Dodgers!”

His awe never compromised his neutrality. “I think it was a New York thing,” he says. “We were above cheerleading. I remember once we went to Philadelphia, and a Philadelphia writer showed up in the press box with a Phillies cap on. He was scorned. We felt in New York we were reporters, not pompon girls.”

Some front-office colleagues took the typically New York attitude that they were slumming among the uninitiated, rubes who knew nothing of the game of baseball. Scully tactfully took to going to as many luncheons as they could schedule. He put the right smiling face on the community’s new neighbors -- and representatives. He took the we out of broadcasting but put the our in community relations.

“I knew they knew baseball out here,” Scully says. “It was just some of the individual players they weren’t familiar with. Oh sure, they knew the stars, the Reeses, the Drysdales, Sniders, Furillos. But I take no credit for the transistor tune-ins. You have to remember when we played in the Coliseum, some of those fans were 79 rows up, a half-mile from the action. It made sense to bring a radio.”

It was Scully’s finest year, 1958.

“We knew we had a bad team,” he says. “A decision had to be reached whether to go with the established stars or try to run in a bunch of unknown kids. It was decided to go with the name players.”

Scully sold Los Angeles on the Dodgers -- with a team that finished next to last. Scully was the master at distracting attention from the inept, the boring. He didn’t broadcast a game, he narrated it.

Scully could have left the Dodgers. Network contracts in the high millions were dangled. And sometimes accepted. The temptation not to have to get in a car and drive down the freeway to the ballpark every night must have been enticing.

But he found life without the Dodgers unthinkable. Scully without the Dodgers was Caruso without an opera, any troubadour without a song.

He kept his feet in the shoals of celebrity. “In New York, I was a guy who rode the subway to work and lived in a fifth-floor walk-up. To the neighborhood, I was just a guy who worked nights.”

He still works nights. And the Dodgers are glad of it.

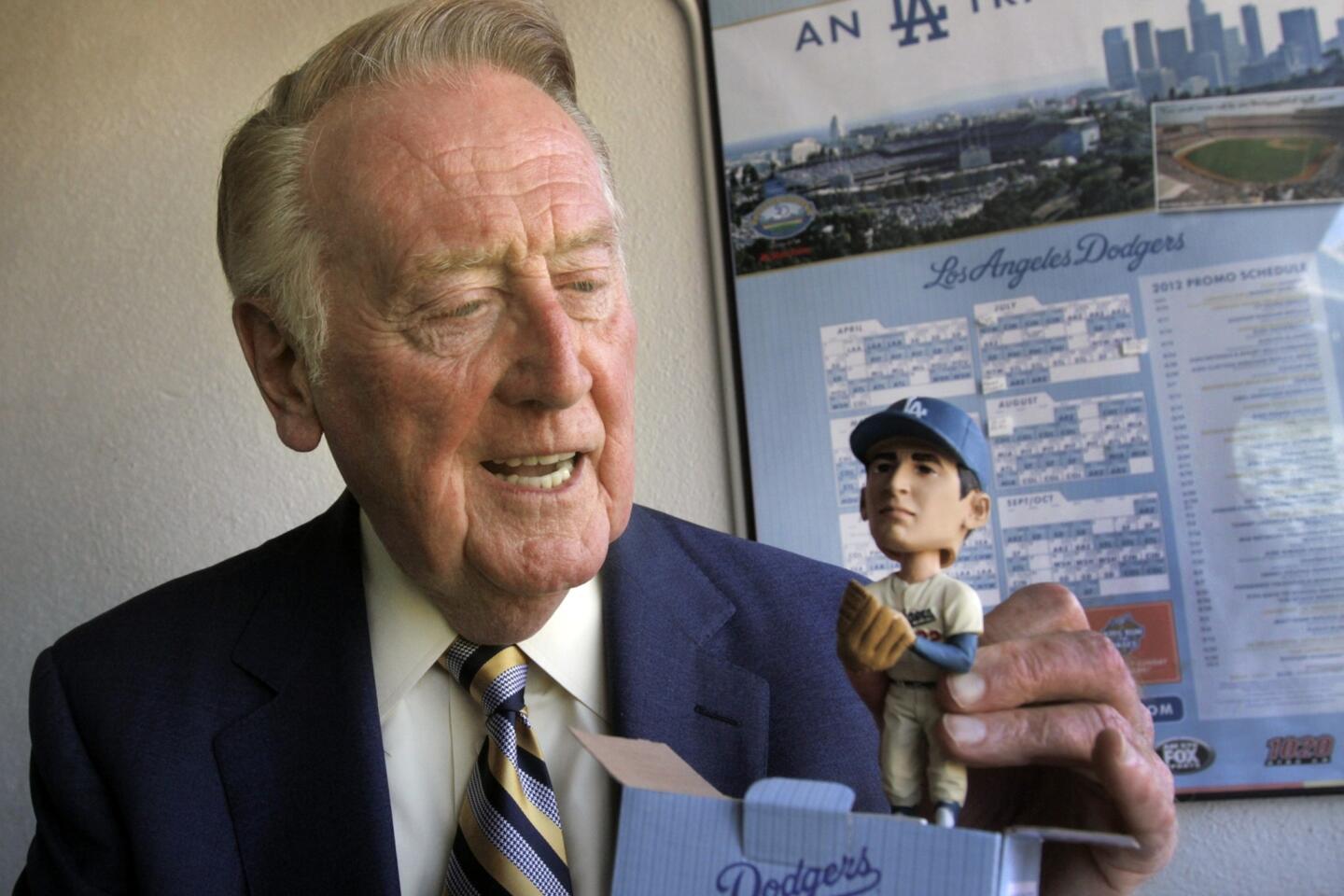

Scully was probably the least surprised guy in the ballpark when the Dodgers blew an eight-run lead in the ninth the other night. “The Dodgers never do anything easy,” he says. “They don’t win easy -- and they don’t lose easy. But I’ll tell you something: They have seemed to be touched ever since they came to L.A. Call it magic or luck, but just when things get to their worst, somebody touches a wand and here comes a Koufax or a Larry Sherry or a Maury Wills or a Kirk Gibson.”

The Dodgers are an outfit you’d want to get next to in a lifeboat.

But if there’s one thing Scully decries today, it’s what he calls “single-file baseball.” He explains: “We used to do things together. So did the team. We went by train but even when we moved West, on the days off, the whole organization got together for a golf outing.

“Now, the players arrive in single file. They get dressed in single file. If they do get on the team bus, they get on one by one. They sit behind each other on airplanes. Sometimes you think it’s a clubhouse of strangers.”

The Dodgers are 100 years old. Scully has been with them almost 40. In that time, attendances of 2 million -- thought impossible for a baseball franchise -- became commonplace in Los Angeles. Then, 3-million attendances were achieved six times.

Scully was there for all of them. It may have been a coincidence, but I think not. Scully will never be MVP -- most valuable player. But he has to be MVD -- most valuable Dodger.

This is a reprint of a column published on Aug. 26, 1990.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.