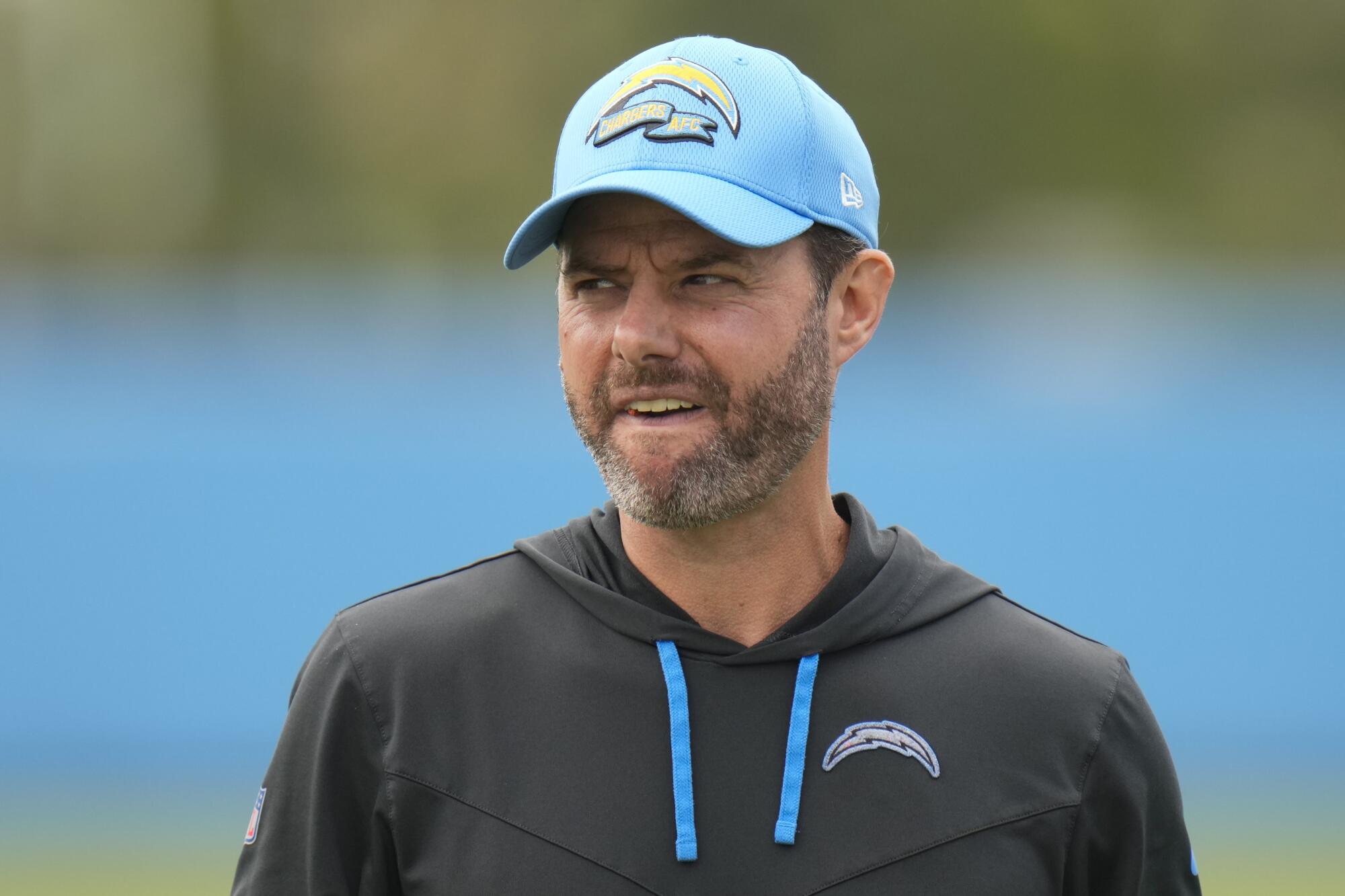

Brandon Staley watched his parents battle cancer and then had his own bout, but the Chargers coach believes the experience can help him be a stronger coach.

- Share via

The losses were dramatic, certainly, even historic, the Chargers’ last two seasons ending in ways difficult to conceive.

But Brandon Staley is one who can relate, can relate to being repeatedly crushed, to being finished in both mind and body. Can relate to the pain of progress.

He’s a fighter who, still today, summons the competitive acid that swells inside a gut trying to accept losses suffered on an AAU hoops court as a 12-year-old.

And he’s a son, too, a son who watched his mother somehow cut daylight through the impossible — a winding, gnarled cancer battle that he’d eventually have to face himself.

“Because of the tough losses, the endings to the past two seasons, you’re closer to the right path,” Staley said. “It’s exactly what my mom used to always say to us.”

Linda Staley’s message has shaped his life. Her words are, as Staley explained it, “what drive me from these experiences.”

Still stinging from the third-worst collapse in NFL playoff history, Chargers coach Brandon Staley met with Warriors coach Steve Kerr, who had been there before.

He used them years ago when Hodgkin lymphoma invaded his chest and demanded a response to a regimen that gives life and hope but takes so much else.

“Every one of those chemo treatments was like a football game to him,” Jason, Staley’s twin brother, remembered. “It was going to be a grind … and he was going to grind the cancer right out of him.”

So now, Staley is in another fight — one that isn’t life or death just a whole lot of life, his life. For the second consecutive summer, he will try to steer the Chargers back from the darkest of defeats.

Understanding cancer and its ravages long before his diagnosis — the way the disease slowly consumed his mother and twice took runs at his father — Staley finds himself empowered by perspective.

“When you go through chemo, a treatment, afterward you have nothing left,” he said. “It feels like losing a game. It takes the air out of you. But 13 days later you have to be ready to go do it again.

“You know what to expect now, so you build yourself up and when that date arrives, you’re ready to go. And then you’re actually stronger the next time. You’re going to get knocked down again by the treatment, but you keep learning.”

The Chargers’ latest loss was so profound that the details and misery attached to it — the entire expanse of a sour-luck franchise that, in 54 years in the NFL, never has won — can be captured in a single word:

Jacksonville.

Expressed another way, it takes but two numbers:

27-0.

The league’s third-worst playoff collapse spiraled the Chargers into an offseason that saw multiple assistants fired by a coach many observers believed should have been the first to go.

Worse, the 31-30 loss to the Jaguars marked Staley’s second consecutive season-ending stomach kick. A year earlier, the Chargers’ playoffs hopes vanished on the final play of the NFL’s final regular-season game, in overtime, against the AFC West rival Raiders.

Despite starting his career with consecutive winning seasons — a more successful foundation than those laid by Bill Belichick and Andy Reid, Jimmy Johnson and Don Coryell — Staley’s very competence was doubted. Even mocked.

The analysts screamed, the fans growled, the internet “internetted.”

So, as he readies for his latest response in a lifetime of responses, let’s offer one suggestion of what’s to come by looking back at what already has been; back at the time a disease showed up to attack Staley but instead found itself under attack.

“I know what the toughest part of life looks like because I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it and I’ve felt it myself.”

— Brandon Staley, Chargers coach

He had just spent his first year in coaching — at Northern Illinois — as a graduate assistant, a bottom-rung position where a former college standout found himself trying to discover ways to somehow impact games he previously had controlled joystick-like as a quarterback.

Staley hadn’t felt well for most of that 2006 season as he dealt with a stubborn fever and re-occurring night sweats, a growth also developing on his neck and eventually turning harder.

In mid-January, at UH Cleveland Medical Center — the same hospital where his parents had been treated — Staley received the diagnosis that left both his brothers crying while he refused to waver.

“Brandon’s wired differently than a lot of people,” said Michael, Staley’s younger brother. “I think it was tough for him to break the news to me, but the confidence he had on that call made me feel more at ease.

“He wasn’t going to let people see him differently even though he was battling something terrifying. He approached things the way we saw our mom do it. She fought with such grace and elegance.”

Linda Staley was supposed to live one year after breast cancer was discovered when her twin sons were 12. She lived that year and eight more before her body spent the last of its fight.

Along the way, she discovered strength by helping others on their cancer paths, continued to raise her three sons and, shining light on the grim effects of chemo, often leaned on her favorite mantra: “The sicker I get, the closer I get to getting well.”

Staley’s father, Bruce, already had beaten thyroid cancer and, years later, would do the same to prostate cancer. But Brandon’s diagnosis hit especially hard, Michael admitting he felt fear and Jason saying he experienced something more gripping.

“There was nothing I wouldn’t have done to take the cancer out of him and put it into me,” Jason said. “I mean, we’re twins, right? That’s something I have to wake up with every day. We’re blessed that he beat it, but there’s still a tinge of guilt, a bit of ‘Why him and not me?’ ”

Twelve rounds of chemo — once every other week for six months — awaited Staley. Lymphoma filled his right lung and his tumor had grown to be as visible as ever.

New Chargers coach Brandon Staley credits much of his success to the examples set by his father and mother, even as she eventually passed away from cancer.

There were unknowns, certainly, but there also was a clear picture of what was coming; a picture, Staley explained, fine-tuned by watching a pair of lifelong educators who raised him teach lessons they never envisioned teaching.

“I saw a lot from my mom and dad, especially my mom,” he said. “She went through the toughest stuff you can go through. … There was nothing in the cancer playbook that she didn’t go through.

“I’ve seen how far the human body can go. I’ve seen it challenged to the edges. I know what the toughest part of life looks like because I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it and I’ve felt it myself.”

After the ninth round of chemo, scans showed Staley to be cancer free. But the final three dosages had to go on as planned, something he said nearly staggered a mindset forged to fight.

So Brandon Zangaro, one of his former college teammates, continued to pick up Staley at the Cleveland airport, drive him to the hospital and marvel at what would happen once they arrived.

“When he would walk in, everyone’s day would brighten,” Zangaro said. “He’s just magnifying that way, electric really. It was ironic, you know? He was going there to have poison put in his body and he was the positive one.”

Following the chemo and a short break, Staley began six weeks of radiation, every morning, Monday through Friday. He would drive to Chicago, to the University of Illinois Medical Center, leaving Northern Illinois at 4 a.m. for the earliest appointment possible.

Then he’d drive back and return to work, resume building toward his dream of head coaching, the competitor in Staley choosing to embrace — no, to cherish — the two-fisted challenger before him.

The early-morning regimen brought a focus and purpose to each day. The battle generated the sort of energy he’d felt only when facing the toughest of foes. The size of the opponent demanded a response of equal stature.

Austin Ekeler is just what NFL teams want in a running back. He can run inside and out and catch like a wide receiver. He scored 18 touchdowns last season. Yet, where’s the pay?

“It was really good for me because it got me started in coaching the way you need to start,” Staley said, “which is having the selflessness, the commitment, the dedication, the drive that ultimately gets you where you want to go.”

Every day, after returning from radiation, Staley would enter the Yordon Center, which houses Northern Illinois’ football offices. Amy Ward, a former Huskie volleyball player who was interning for the athletic director, worked the front desk.

The two had seen each other months earlier, at Fatty’s, a local hangout known for its Cajun-fried potato salad and less famous for being Amy’s former place of employment.

She would see Staley stalking his way through the Yordon Center hallways behind dark sunglasses. What Amy didn’t know was those glasses were hiding a pair of eyes turned bloodshot by the drugs saving Staley’s life.

Before long, they were dating, and a couple weeks into their relationship, Amy asked about the scar on Staley’s neck, the spot that twice had been biopsied leading to his diagnosis.

“I was enamored at his ease in discussing his cancer,” said Amy, who became Staley’s wife in June 2011. “You could tell it was a big deal and it had been really hard, but he was, like, on fire about his life and what he wanted to do next.”

There was passion, but there was something soothing, too. There was authenticity, the type Staley’s players talk about still today. Before their first date, Staley told Amy he’d pick her up in his favorite car, bragging on his beloved ride to the point where Amy wasn’t sure what to expect.

He’s a car guy? Really?

Then Staley rolled up in an old Buick Skylark the color of the McDonald’s character, Grimace. “The Purple Palace,” as the Staley boys called it, had belonged to their grandfather, John Lucrezi, before being passed down.

There was gray paneling on the sides and some 250,000 miles on the odometer — Jason: “He drove it everywhere. We couldn’t afford plane tickets.” — before the poor palace, oozing oil, finally caught fire and died.

“He pulled up in that Skylark with a big smile on his face, and I was like, ‘OK, this guy’s different,’ ” Amy said. “It was just so refreshing. I knew then how original he was.”

His life already buoyed by belief, Staley described himself as soaring when he appeared on the other side of cancer. His confidence surged like never before, and he worked himself into better shape than when he was quarterbacking at Dayton.

“The culture this year is so much better, so much closer, so much tighter. That’s a testament to Staley, to what he’s building. This is his thing, his baby. This is 100% him.”

— Sebastian Joseph-Day, Chargers defensive lineman

He knew he had conquered a monumental climb and just how much it had taken to reach the peak. Bigger still, Staley said, he now knew how to get where he really was going.

“There’s a humility when you know how it is and how it could be,” he said. “When you feel that type of stuff I felt, then everything else seems so achievable. There isn’t a challenge that you don’t think you can head toward.”

Staley spent two more years at Northern Illinois before starting up the ladder that saw him reach Division III John Carroll for a three-year defensive coordinator run that ended in 2016.

Before his final season there, Staley, two defensive assistants and eight members of his secondary loaded into an extended van and drove two hours down I-76 to Pittsburgh, to Heinz Field, for “Race to Anyplace,” a stationary bike charity event for cancer.

With a Chargers season under his belt, defensive tackle Sebastian Joseph-Day says the chemistry in Year 2 of this revamped defense will prove powerful.

Even now, Staley is convinced that the trip bonded the group, helping the ’16 John Carroll team play the best defense he has “ever been a part of … and I’ve been a part of two No. 1 defenses in the NFL.”

“A lot of people talk a good game, but he lived a good game,” said Mike Hollins, one of Staley’s former John Carroll cornerbacks. “What he overcame showed us we could overcome anything.”

That season, Staley was named the Division III national coordinator of the year. A few months later, he was coaching outside linebackers for the Chicago Bears, an NFL assistant sprinting his way to another pinnacle with the Chargers.

Flying home from Jacksonville, Staley said he remembers wishing the NFL playoffs were like pickup basketball; he wanted to run it back against the Jaguars right then.

The next day, his brothers talked to him in separate phone conversations, both Jason and Michael saying Staley stressed to them the importance of his upcoming exit interviews with the players.

Here was a coach just flattened again by a season-sealing defeat, a coach rumored to be in danger of facing unemployment, still trying to end the year the right way, even after the season had ended with everything going wrong.

Six months later, there’s evidence of healing.

“The culture this year is so much better, so much closer, so much tighter,” Chargers defensive lineman Sebastian Joseph-Day said. “That’s a testament to Staley, to what he’s building. This is his thing, his baby. This is 100% him.”

Perhaps, but Staley insisted it’s a team thing, not unlike his fight against Hodgkin lymphoma; a fight that focused on one man but featured the efforts of so many others.

“You don’t do it by yourself,” Staley said. “You can’t do it alone. You have to depend on your doctors and your nurses, your family and your friends. That’s how being a head coach is, too.

“If you feel like you can do it all by yourself, you’re going to fail. You won’t have enough on your own. That’s why you have to surround yourself with the right people. I’m not the one who beat cancer. We all did it.”

The toughness required, the unpredictability involved, the perseverance needed — Staley cited each when he compared fighting cancer to head coaching in the NFL. In both challenges, he talked about the ability to feel momentum turn.

Then he talked about the Chargers’ Week 14 victory last season over Miami, when a group sitting at 6-6 made one of the league’s fastest offenses trudge through mud, igniting a four-game win streak that put his Chargers in the playoffs.

“I look back on my cancer path,” Staley said, “and it’s helped me immensely.”

Each of his first two teams as a head coach had its season end when the opposition kicked a field goal as time expired. The bankrupt feeling of those empty nights — after so many fulfilling moments to get there — was conveyed poignantly by “0:00.”

Now, Season 3 is beginning for Staley, and the people closest to him have little doubt how this cancer survivor will respond.

“I’ve seen so many things thrown his way where I think so many people would have given up or taken a different direction,” Amy said. “He just digs in deeper and keeps going. I’ve always admired that about him. When you think his back’s to the wall, he’s just getting started.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.