His dad was a cop in the Bronx, but it was baseball that saved Andrew Velazquez

- Share via

Andrew Velazquez was a teenager in the Bronx, N.Y., when he reached a crossroads in life, with one track leading toward a potential future in baseball and the other down a path of possible destruction.

If the kid who would grow up to be this year’s Angels shortstop, a diminutive defensive whiz who has transformed the infield with his spectacular play, didn’t see the whole situation clearly at the time, his father did.

Kenneth Velazquez grew up in South Bronx, in the Moore Houses projects on East 149th Street and Jackson Avenue. He spent 20 years in the New York Police Department, working undercover in narcotics during the crack-cocaine epidemic and as a detective in the 42nd Precinct near Yankee Stadium.

The summer Andrew turned 14, Kenneth saw his son drifting away from baseball — skipping practices with his youth team, declining to try out for the Gothams, a New York City-based travel-ball program — and toward the temptations he saw destroy so many lives.

The Anaheim City Council voted to halt the sale of Angel Stadium. Here are questions and answers that could affect the Angels’ long-term plans.

“He wasn’t running in the streets, but he was hanging out with people that he didn’t normally hang out with, or kids who were turning the wrong way,” Kenneth said. “I was a cop. I knew it.

“So I told him, ‘Those kids are no good. You should steer clear of them. But I’m gonna give you the leash. You go and find out what you want to do in your life.’ ”

A few weeks later, while driving in the family car, Andrew told his father he wanted to play travel ball, “and ever since that day, his effort has been a thousand percent,” Kenneth said. “Once he determined that this is what he wanted to do with his life, it was just nonstop.”

Velazquez carried that work ethic to high school at Fordham Prep — alma mater of Hall of Fame infielder Frankie Frisch and Vin Scully — and throughout an 11-year professional career that meandered through six organizations and 10 minor league towns, included one brief but memorable stop with his hometown New York Yankees, and finally has gained traction in Anaheim.

Velazquez spent parts of four seasons, from 2018-21, in the big leagues with Tampa Bay, Cleveland, Baltimore and New York. He lived out his childhood dream by playing 35 games for the Yankees last summer, starting 20 of them at shortstop, the position of his boyhood idol, Derek Jeter.

But when Velazquez returns to the Bronx this week with the Angels, who open a three-game series against the American League East-leading Yankees on Tuesday, it will be as a big league starter, one of the game’s best defensive shortstops, and a son who remains grateful his parents allowed him to choose his own destiny.

“I was friends with some kids who were doing drugs and stuff, some who eventually died from it, but I wasn’t into that,” Velazquez, 27, said of those turbulent teenage years. “My dad grew up in the projects and was a police officer, so maybe he could see the beginnings of it.

“As scary as it is for a parent, kudos to them for allowing me to make the decision, because I probably deserved an ass-whooping at one point. They were kind of like, ‘You want to do that? You’re on your own.’ We were getting close to the point where they maybe had to straighten me out. But I made the right decision.”

The Angels would concur. The 5-foot-9, 170-pound Velazquez might not be a force at the plate, but he’s been a game-changer on defense since being recalled from triple A in early April to replace the injured David Fletcher.

Velazquez has eight defensive runs saved through Sunday’s game against Toronto, according to Sports Info Solutions, second among major league shortstops and a huge upgrade over last year’s shortstop, Jose Iglesias, who ranked last among shortstops with at least 500 innings.

Velazquez has made diving stops of grounders and line drives to his left and right. He’s started and turned numerous double plays. He’s backhanded grounders in the hole and, with his momentum carrying him toward the outfield, made long throws to first. He’s ranged far to his left for grounders and made strong, across-the-body throws to first. He’s sprinted into the outfield to catch popups.

In a May 8 win over Washington, Velazquez, stationed on the second-base side of the bag, dived up the middle to stop Juan Soto’s bases-loaded grounder, scrambled to his knees and made a 12-foot, around-the-back pass to second baseman Tyler Wade for the out, saving a run.

“If this guy starts hitting, nobody’s gonna be able to afford him,” Angels manager Joe Maddon said after that game. “I mean, he’s that good at shortstop.”

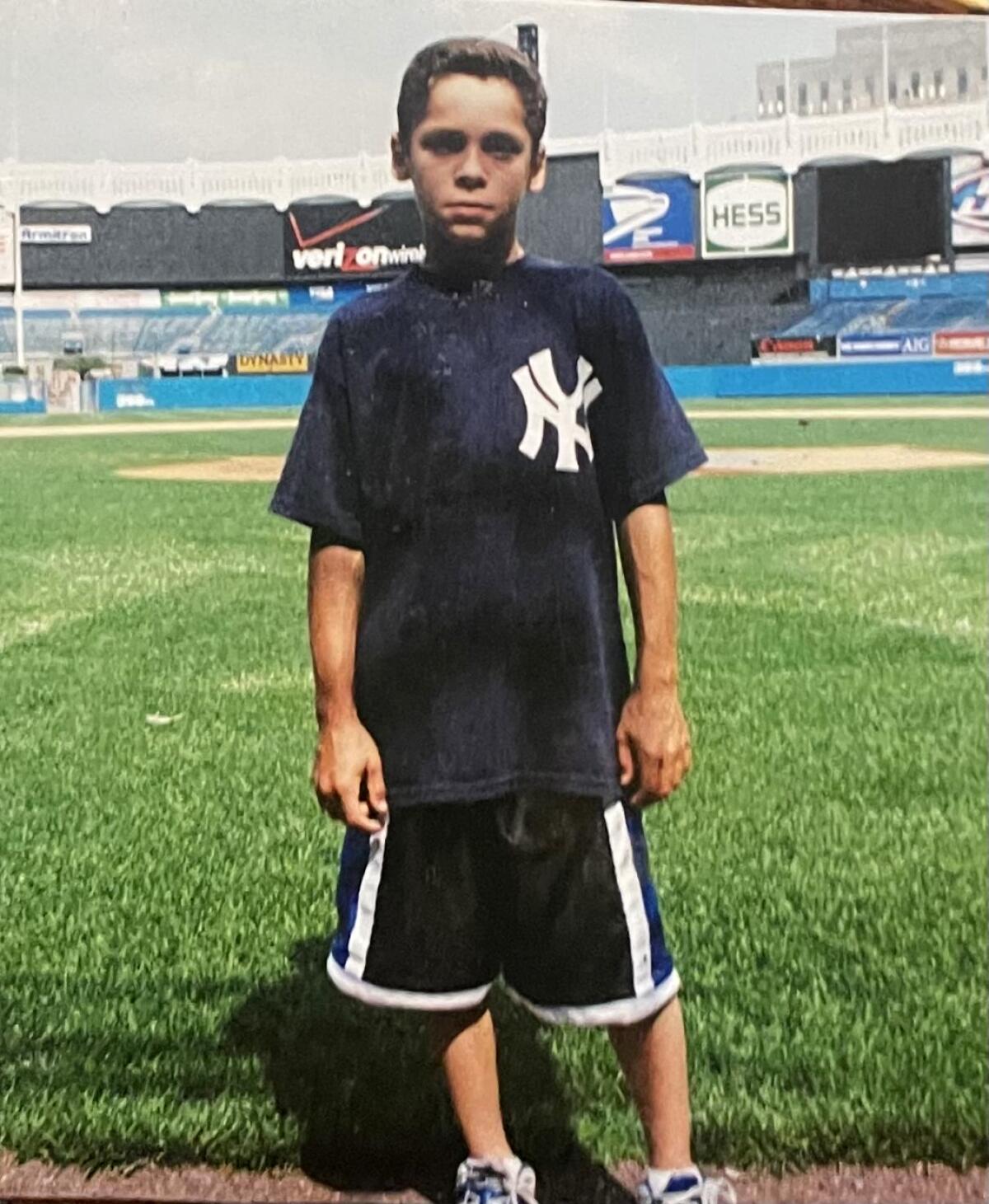

Velazquez wasn’t always that good. He grew up fielding grounders on the rock-strewn, patchy grass fields of the Bronx, including one at Macombs Dam Park, across the street from old Yankee Stadium.

“He dreaded those fields,” Kenneth Velazquez said. “A guy would hit him 150 to 200 grounders, and I thought he was gonna take his head off. They were all bad hops.”

Those surfaces were an upgrade from the public park across the street from Velazquez’s house in the Morris Park section of the Bronx.

“That had a concrete softball field, and I would be diving on it as a kid,” Andrew said. “We got it anywhere we could.”

Velazquez was athletic and fast as a teenager, with a strong arm and a quick bat, and he improved under the tutelage of trainer Luis Santos and former minor league infielder Rich Almanzar, both natives of the Dominican Republic who worked with New York City prospects.

Still, Velazquez didn’t start at Fordham Prep until his junior year and didn’t play shortstop until he was a senior. A standout performance at a tournament in Georgia before his senior year — Velazquez went 14 for 16 and played stellar defense — put him on the radar of scouts and college coaches.

Velazquez turned down a scholarship to Virginia Tech to sign for $200,000 with Arizona, which picked him in the seventh round of the 2012 draft.

A polished prospect, Velazquez wasn’t. There was so much movement in his arms and hands as he fielded grounders in the Arizona rookie league that summer that a Diamondbacks instructor began calling him “Pulpo,” the Spanish word for octopus, Kenneth said.

That was shortened to “Squid,” and the nickname stuck. Those tentacle-like hands and arms have quieted over the years, though, so much so that his Angels teammates wore T-shirts on Sunday that read: “70% of the world is covered by water. The rest is covered by Squid.”

“He’s always calm, he’s always very relaxed, under control,” first baseman Jared Walsh said. “He never looks jumpy in the field. You watch him, and he lets the ball come to him. He’s super smooth.”

The switch-hitting Velazquez has mixed in a little more offense to go with his slick fielding, batting .286 (18 for 63) with two homers, three doubles and eight RBIs in 18 games from May 9 through Saturday to raise his average from .131 to .210 before going 0 for 5 on Sunday.

“Just trying to hit more strikes,” Velazquez said. “It’s easier said than done.”

Shohei Ohtani hits two home runs, but the bullpen can’t keep the lead in the slugfest, giving up five runs in an 11-10 loss to the Toronto Blue Jays.

Maddon has made it clear that Velazquez’s glove will play no matter how he hits. When Velazquez was batting .130 in early May, Maddon said, “I really don’t care, because the impact he’s had on the game out there has been substantial.”

The security of his first big league starting job won’t change Velazquez’s approach. He’s played in too many minor league games and was released and traded too many times to get comfortable here. He didn’t even make the Angels’ opening-day roster. He just had his car shipped to Southern California a few weeks ago.

“I heard Aaron Judge say something last year, that we’re all fighting for a job every day,” Velazquez said, referring to the Yankees slugger. “That’s the mind-set I have. Going up and down enough times will humble you. I still have options. Right when you think, ‘I’m here,’ that’s when they say, ‘OK, we’re sending you down.’ ”

Velazquez played similarly in his brief stint with the Yankees last season, batting .224 with six RBIs, an experience he described as “surreal, like a dream come true, the culmination of everything I did beforehand to get to that moment.”

But once shortstop Gleyber Torres returned from injury, Velazquez went to the bench. Velazquez wasn’t protected on the 40-man roster after the season, and the Angels claimed him off waivers last November.

Mike Trout’s home run in the seventh regained the Angels’ lead before the Toronto Blue Jays rallied with a three-run eighth to take a 6-5 win.

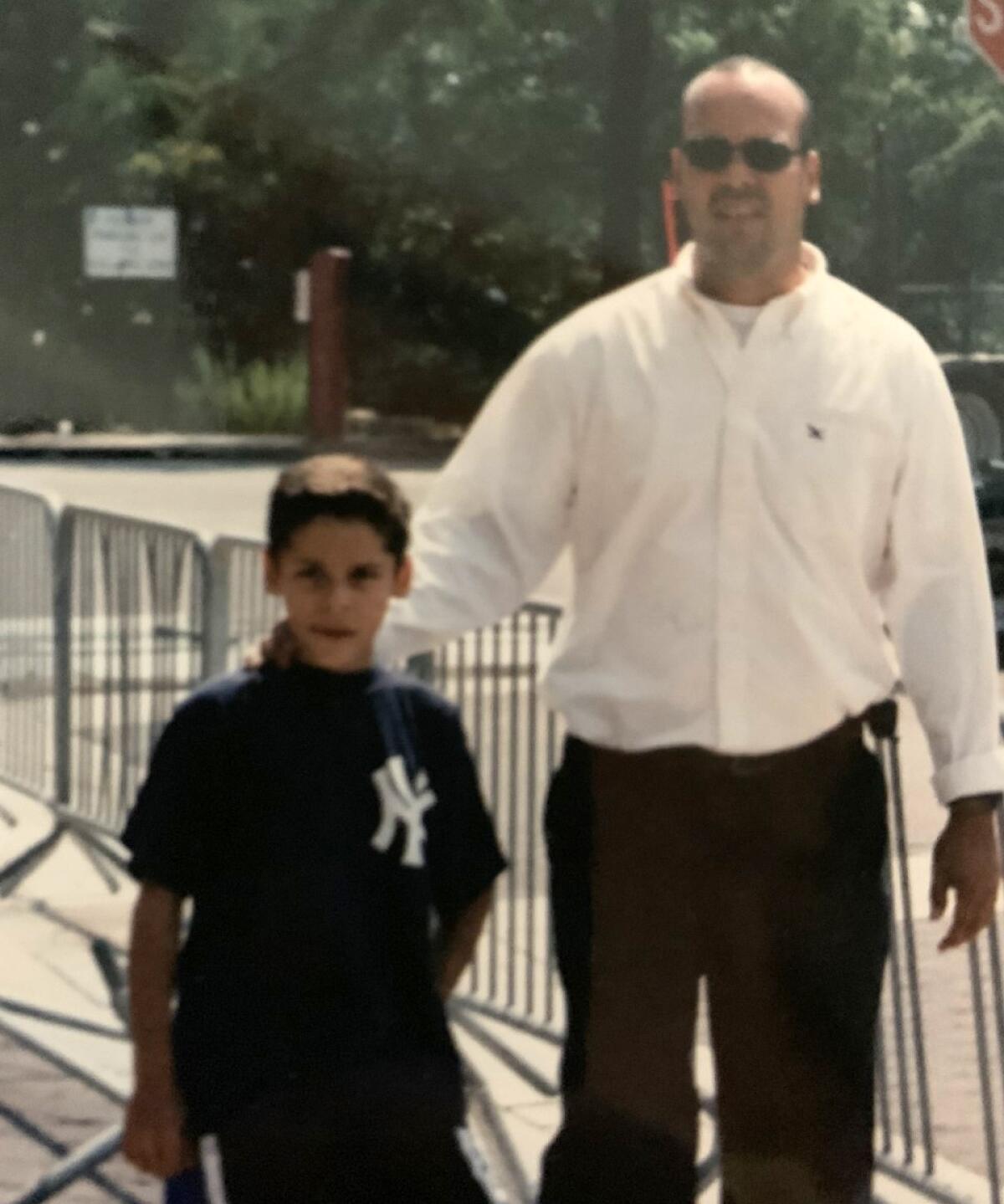

As thrilling as it was for Kenneth Velazquez, a lifelong Yankees fan who works as an assistant baseball coach at St. Ramon’s High in the Bronx, and his wife, Margaret, a retired school teacher, to see their son in Yankees pinstripes, it will be equally gratifying to see him return home as a big league regular this week.

Whether Velazquez makes a dazzling defensive play or delivers a clutch hit, his mere presence in Yankee Stadium is further proof that his parents’ hands-off approach during Andrew’s formative years, as difficult as it was at the time, was the right one.

“We trusted our son and raised him to make right choices, but you keep one eye open,” Kenneth Velazquez said. “You don’t want to lose your kid to the streets. He was tempted. He saw it. He didn’t like it. This is what he wanted, and he set his mind to it. This was his dream since he was a kid.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.