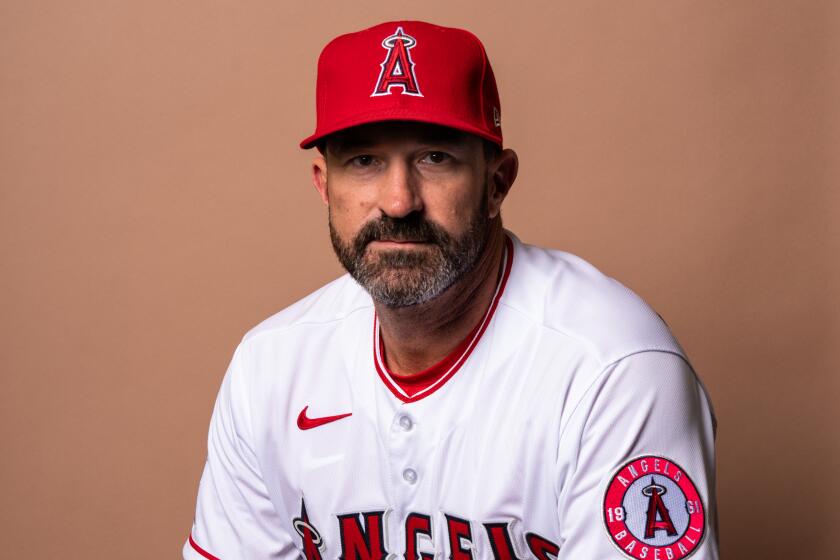

Allegations against Angels’ Mickey Callaway prompt scrutiny of MLB hiring practices

- Share via

Among the numerous quotes from the unnamed women who accused Angels pitching coach Mickey Callaway of sexual harassment in a story published by the Athletic this week, this one might be the most damning to Major League Baseball and its 30 teams:

“It was the worst-kept secret in sports.”

Callaway, the sports news website alleged, “aggressively pursued” at least five women in the sports media industry over the course of five years, sending three women inappropriate photographs and asking one to send nude photos in return.

In one instance, Callaway “thrust his crotch near the face of a reporter as she interviewed him.” In another, he told a woman that “if she got drunk with him, he’d share information about the [New York] Mets.”

The behavior reportedly took place while Callaway was the Cleveland pitching coach from 2013-2017, yet that didn’t stop the Mets from hiring him as manager in October 2017. It reportedly continued in New York, but that didn’t stop the Angels from hiring Callaway before the 2020 season.

A look why Angels have not fired pitching coach Mickey Callaway, who is accused of inappropriate behavior toward women in media.

“It makes you look negligent,” said Dr. John Sullivan, a retired San Francisco State professor of management who has advised numerous Silicon Valley companies, including Google, Facebook and Twitter, on how to vet candidates for past sexual harassment issues. “You should have checked. You should have known.”

The Angels suspended Callaway, 45, on Tuesday pending an investigation into his behavior, giving MLB its second black eye in two weeks. The Mets fired newly hired general manager Jared Porter on Jan. 18 after an ESPN report about his sexual harassment of one reporter.

Mets President Sandy Alderson, who hired Porter and was the team’s GM when Callaway was hired, said in a statement that he was “appalled” by Callaway’s reported actions and “unaware of the conduct described in the story at the time of Mickey’s hire or at any time during my tenure as general manager.”

The Angels were likewise surprised.

“Never. Never. No,” Angels manager Joe Maddon said, when asked if he had heard of any sexual harassment-related complaints about Callaway, who briefly pitched for the Angels during their 2002 World Series run.

“We were all in agreement that Mickey was a good choice. You saw what he did in Cleveland. I knew him since the Angels’ World Series days. It was pretty unanimous that he’s a really good pitching coach. Regarding the vetting process, I don’t know what may have been done.”

Pending completion of an investigation into allegations from at least five female reporters, the Angels suspend pitching coach Mickey Calloway.

Whatever was done to screen Callaway and Porter, it clearly wasn’t enough.

“You need to make double sure you’re not hiring someone whose behavior is going to make everyone else’s life miserable,” said Sullivan, who has worked with two major league teams in recent years. “What is the cost of hiring a jerk? How many people will suffer? Baseball needs to do better.”

But how?

Alderson said the Mets “have already begun a review of our hiring processes to ensure our vetting of new employees is more thorough and comprehensive,” but he did not provide details.

Cleveland President Chris Antonetti said on a Thursday video call that he was “disturbed, distraught and saddened” by Callaway’s reported behavior, and that the team will “redouble our efforts and make sure we have a safe and inclusive environment.”

The Times reached out to GMs and team presidents from a dozen other clubs, including the Angels, as well as former Angels GM Billy Eppler, who hired Callaway, to inquire about existing vetting processes and how they could be improved.

Nine, including Eppler, didn’t respond, and three politely declined comment, an indication of how sensitive the topic is.

“Each team has its own process, which includes background checks and the like,” one executive said. “I’m certain there’s no such thing as a perfect process.”

MLB is conducting separate investigations of Porter and Callaway and is reviewing existing sexual harassment policies to determine how they can be strengthened.

The board of the Baseball Writers Assn. of America met last week with Patrick Courtney, MLB chief communications officer, and Michele Meyer-Shipp, the league’s new Chief People & Culture officer, to discuss what actions could be taken to combat sexual harassment in the game.

Among them are a third-party hotline that MLB is setting up for media members to report misconduct or issues of concern, posting MLB’s workplace code of conduct more prominently in clubhouses and making sexual harassment a subject of continuing education, not just a single presentation in spring training.

But the league — which did not make Meyer-Shipp available for comment — can only do so much. Each club is responsible for its own hires, and it’s incumbent on them to dig deeper into the backgrounds of potential front-office and on-field personnel.

In addition to the standard reference checks, Sullivan suggests teams hire private detective agencies to conduct FBI-level background checks, which include interviews with colleagues from past jobs and thorough reviews of publicly available legal and divorce records for evidence of sexual harassment or domestic violence.

Sullivan also recommends hiring social media experts to seek out pictures, jokes, comments and behaviors from candidates that could embarrass the team.

“Private detectives, former FBI agents, can find out anything, and social media experts can find anything you’ve posted in your entire life,” Sullivan said. “The FBI literally visits people. They come into the office to conduct interviews. They don’t just call or send a text message.

“They don’t ask ‘yes’ questions. They know how people lie and tell mistruths. They check every place you’ve been. They go through the whole nine yards. The FBI has a process. It’s just incredibly expensive, and it takes awhile. … I’ve never known anyone in pro sports to do that. I don’t know why they don’t.”

Another must, in the eyes of Sullivan: Teams should make candidates aware that if they fail to reveal any past sexual harassment issues, they will be fired immediately. This clause should be included in every contract.

“It scares them from lying,” Sullivan said. “If you lie and embarrass us, you’re not gonna work here.”

The challenges facing human resources departments and front-office executives who screen job applicants is that there is no legal requirement for those with knowledge of misconduct to participate in the process or to tell the truth. And a cursory background check probably won’t turn up sexual-harassment issues.

The victims of sexual harassment are often reluctant to come forward, so it’s imperative for teams to create working conditions in which employees feel safe and comfortable sharing their experiences with club and league officials without fear of reprisal.

The more such inappropriate behavior is exposed, the less chance a sexual harasser has of remaining on the job — or getting another one.

“To the extent that anyone did see or observe any of those behaviors, they were never reported or shared,” Antonetti, the Cleveland team president, said of the Callaway accusations. “Had we known the behaviors described in the article, we would have acted upon it, but we didn’t.

“We do have outlets in place for people to share when inappropriate behavior happens in the workplace, both internally and through the MLB hotline. But it’s clear those aren’t sufficient … because behaviors like this are happening, and that’s not OK.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.