Short season perils: Angels’ Mark Langston left a no-hitter after seven innings

- Share via

The evening could not have proceeded more elegantly for the Angels. This was the grand opening, the debut performance from the man upon whom they had lavished more money than any other pitcher in major league history. The first seven words of The Times’ account from that night: “Mark Langston, the Angels’ $16-million man …”

A staggering sum at the time, the money was spread over five years, but never before had a pitcher been guaranteed even $10 million. Expectations were high at Anaheim Stadium on April 11, 1990, and Langston exceeded them.

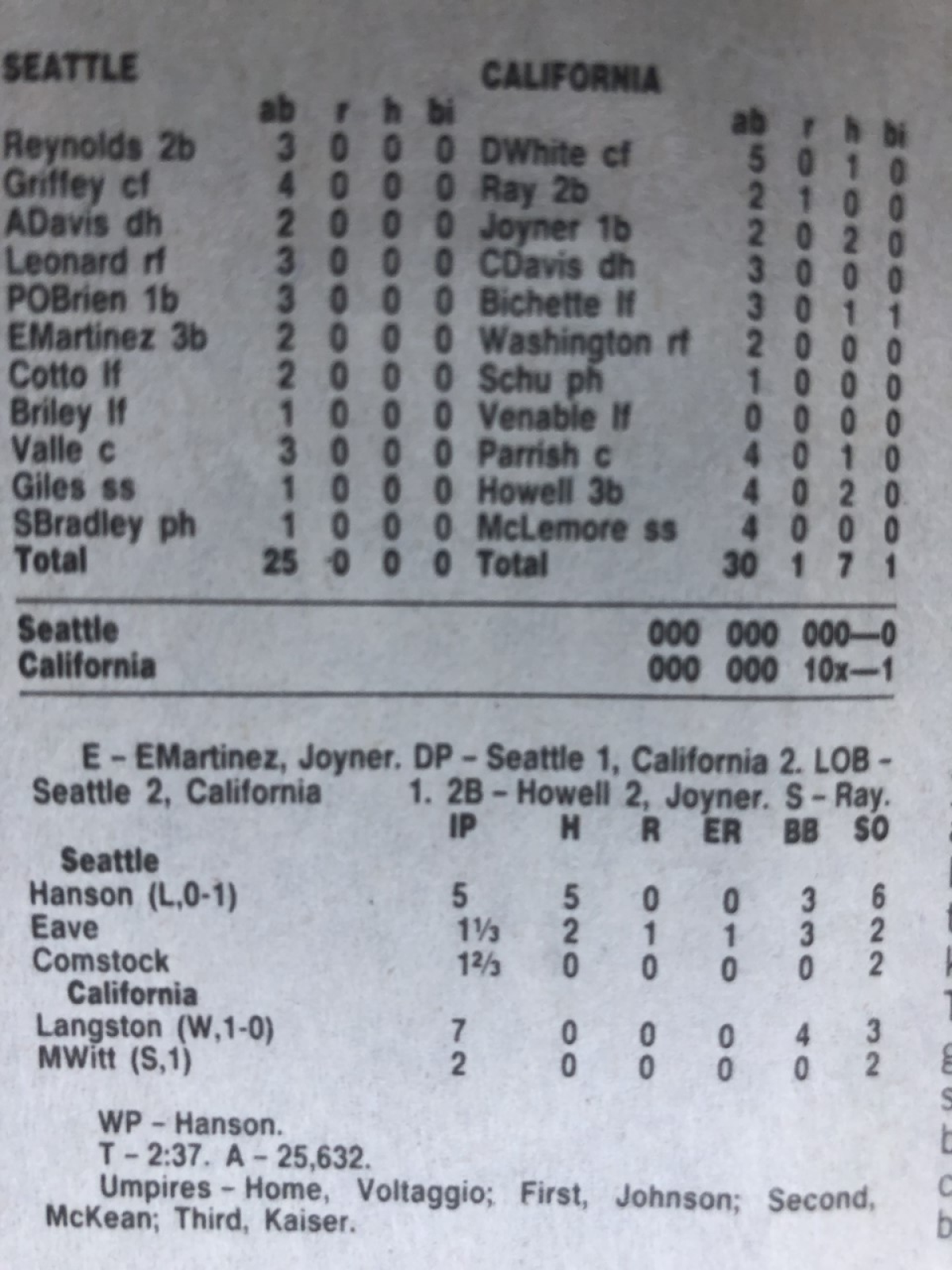

Langston held the Seattle Mariners hitless for seven innings. In the bottom of the seventh, the Angels scored on a bases-loaded walk. Langston was six outs from what would have been the only no-hitter of his distinguished career.

Then the bullpen gate opened, Mike Witt jogged in, and boos cascaded from the stands. The Angels had removed Langston with a no-hitter intact, in what could serve as a cautionary tale for the 2020 season, whenever it might start.

Angels manager Joe Maddon advocates starting the season with fans only watching on TV. Doing so could allow MLB to test pace-of-play initiatives.

None of the booing fans knew it at the time, but Langston had taken himself out of the game.

The shortened 2020 season, assuming there is one, would be preceded by an abbreviated training camp. In 1990, after owners had locked the players out of camp, the two sides reached a new labor agreement March 19. They settled on three weeks of spring training, half the usual time.

In his final start of that shortened spring, Langston worked four innings. In his Angels debut, he expected to throw five, the next step on the usual spring course for a starting pitcher to build his endurance. He got through seven, and he was beyond exhausted.

“There’s no way I could have made two more innings,” Langston said in a telephone interview. “I didn’t have the base underneath me to do that.”

Witt had been warming up, aware that Langston was tiring and unaware of the no-hitter in progress. He had been displaced from the starting rotation by Langston’s arrival and his own horrid spring, but still he wondered why the fans booed him before he had thrown a single pitch.

“I was rooting for Mike anyway,” Angels first baseman Wally Joyner said after the game, “but then I was really rooting for him to shut those people up.”

Witt did, retiring the final six batters in order to complete the no-hitter, and the Angels’ 1-0 victory. The last batter was the youngest player in the major leagues that season, 20-year-old Ken Griffey Jr. The future Hall of Famer struck out swinging.

“To me, it always felt like a glorified spring training game,” Langston said. “It truly did. When they go ‘combined no-hitter’ and all, nah. That wasn’t the feel.”

Mike Port, the Angels’ general manager, watched from his box. In those days, managers ran games without the front office providing a game plan, and Port said he trusted manager Doug Rader to make the right call. Port said he was not surprised Langston was removed, given that the Angels had made a five-year investment in him.

Angels broadcaster Mark Langston was healthy, he assured reporters Sunday. The cardiac event that he amazingly survived has changed his life, he said.

“One of the reasons we went to the length we did to sign him was that he was going to be an integral part of the team,” Port said in a telephone interview.

“It was not, ultimately, about Mark Langston pitching a no-hitter. We wanted him around for the 1990 season, functioning at his best. As much caution as seems to be employed nowadays with respect to pitchers, if the situation were to arise today, I’m sure you’d see much the same thing.”

As it turned out, Rader gave Langston the final say.

“If he had been adamant about staying in, I think we probably would have allowed it,” Rader said after the game. “When he came off the field in the seventh inning, he said, ‘I’m through.’ ”

In 1984, Witt had thrown a perfect game for the Angels.

“It’s tough to come out of a game when you’re throwing a no-hitter,” Witt said after the game in which Langston had done just that. “I don’t know if I would have.”

Langston, a four-time All-Star, said he has no regrets about leaving what could have been his lone career no-hitter. He threw 99 pitches, and for that reason he suspects what happened to him after a short spring 30 years ago would not happen after an abbreviated training camp later this year.

“There’s no way, in today’s scenario, that would ever play out,” Langston said. “If they only had three weeks of spring training, they would not let a guy throw close to 100 pitches, never in a zillion years.

“In those days, you did what you could do for as long as you could do it.”

In 1990, the owners proposed a two-week spring training, with a 30-man roster for the first month of the season. The players insisted on a three-week spring training, and the roster was set at 27 for the first three weeks.

If baseball resumes this season, the framework is expected to be similar: an abbreviated training camp, and a season that starts with expanded rosters. Langston, now a broadcaster for the Angels, said he expects the starting pitchers to be ready for opening day.

“The way the game is played in today’s world, they would be more than ready to go those five innings right out of the gate,” he said.

Port, however, raised two concerns. In 1990, he said, reports of an imminent end to the lockout circulated widely, and players reported to camp in good shape. In 2020, the coronavirus outbreak has led to the closure of most gyms, workout facilities and training complexes, and it is uncertain how well a pitcher can keep himself in shape during an indefinite shutdown.

In addition, as Port noted, increased velocity is associated with an increased risk of injury. In 1990, Langston threw his fastball 93-94 mph, well above average at that time. Today, that fastball would be about average, so pitchers who throw so hard would make up much of a team’s staff.

“Maximum effort guys on every pitch probably run a greater risk of injuring themselves,” Port said.

Langston went 10-17 with a 4.40 earned-run average in 1990, the only season from 1987-96 in which his performance ranked below the league average. Port said the short season “might have” played a part in his struggles that year, but Langston said he did not believe it did.

Instead, he pointed to a two-month stretch — June 5 to Aug. 1 — in which he did not win. In eight of the 10 games he started in that skid, the Angels scored no more than one run.

“I don’t think it had to do with anything other than I got into a big mental funk,” he said. “I created that mess in my head.”

As a historical footnote, three of the last five Angels no-hitters have been combined efforts, each with a unique twist: the Langston-Witt no-hitter in the debut of the $16-million man; the Jered Weaver-Jose Arredondo no-hitter in 2008, in a 1-0 loss to the Dodgers; and the Taylor Cole-Felix Pena no-hitter last July, in the first home game after the death of Tyler Skaggs.

And, as Langston acknowledged, there would hardly be any fanfare about a “$16 million man” today.

“The third and fourth guy in the rotation is making close to that,” Langston said, laughing, “and that’s just for a season.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.