A Word, Please: Semicolons aren’t as important as you think

- Share via

When you’re learning to type, the first lesson is the home-row position — the keys where your fingers rest: a s d f j k l ;.

Learning this, you might naturally assume that the semicolon is pretty important — it must be to earn a spot there, right? You might even be a little embarrassed that you’re not well versed in how to use a punctuation mark placed so prominently on every English language keyboard.

Then, if you’re like me, you spend years embarrassed that you don’t use semicolons more and, worse, you aren’t quite sure how.

Well, good news. Semicolons aren’t as important as you think. In fact, in my unscientific observation, many of the best writers avoid them entirely. Some have openly condemned them.

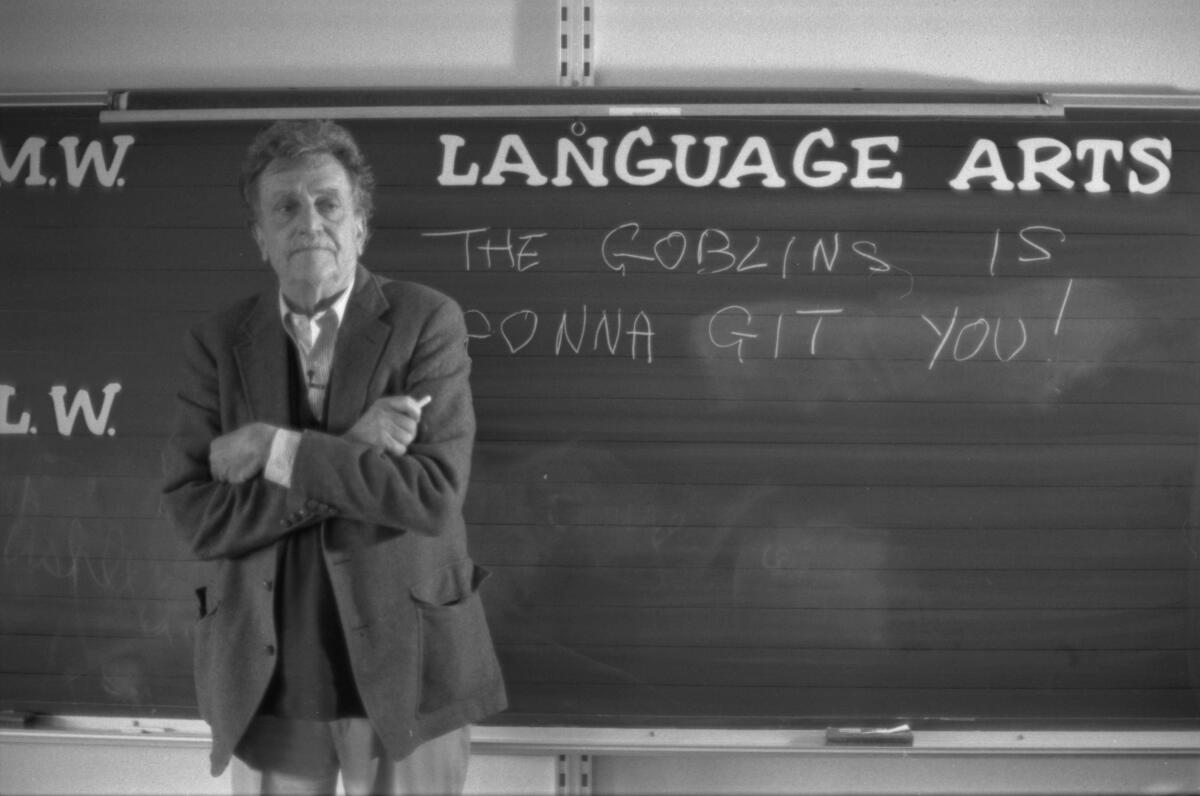

“Do not use semicolons,” Kurt Vonnegut advises aspiring writers in “A Man Without a Country.” “All they do is show you’ve been to college.”

This tracks with my experience as an editor. Most of the semicolons I see do nothing to help the reader. On the contrary, they’re harmful, splicing clear, simple, bite-size ideas into long, cumbersome, hard-to-follow sentences. So why are they there? Often, the only explanation is that the writer wanted to show off that he knows how to use them.

Why do semicolons exist, then? Because sometimes — rarely — they serve a purpose. So it’s a good idea to understand how to use them even as you resolve not to.

Semicolons have two functions. They connect independent clauses, and they work like commas in situations where a comma isn’t strong enough, for example in a list of items that already contain their own commas.

An independent clause is a unit that can stand alone as a sentence because it contains both a subject and a verb: Steve quit. So if independent clauses can stand alone as sentences, why bother connecting them with semicolons? Why not just punctuate them as individual sentences instead? Good question.

Language expert June Casagrande reacts to readers’ objections to questionable grammar, including an instance in her own column.

Sometimes writers want to show that two independent clauses are closely related; they go together. That’s what semicolons do; they tell you that two units that could stand alone as sentences are so important to each other that they should be in the same sentence. But is that really a good reason to force two short, tidy sentences into one long, unwieldy unit?

In my opinion, no. Longer sentences put greater demands on your reader — the mental equivalent of holding your breath till you get to the end. Shorter sentences are more easily digestible. A writer’s job is to deliver information or ideas to readers in the manner most useful to them. So when you start showing off your comma prowess at the reader’s expense, you’ve lost sight of the writer’s purpose.

The worst abuse of semicolons occurs when writers use them to create single-sentence paragraphs. Think about it: If you have a paragraph with just two sentences, it’s obvious those sentences are closely related. So there’s no reason to connect them with a semicolon, creating a single-sentence paragraph.

The other job of semicolons — stringing together items that commas can’t handle — is more practical, sometimes. For example, imagine you’re listing cities where you’ve lived: Burbank, California; Shreveport, Louisiana; Venice, Florida; and Albany, New York. Each of these places contains its own comma. So without semicolons, these four places would be punctuated in a way that suggests they’re actually eight places.

But writers abuse semicolons in this function, too. The punctuation marks make it easy to stuff a bunch of nouns, ideas or actions into a single sentence when shorter sentences would work better. So anytime you’re tempted to lean on semicolons to make sense of your sentence, try breaking it up into shorter sentences instead.

June Casagrande is the author of “The Joy of Syntax: A Simple Guide to All the Grammar You Know You Should Know.” She can be reached at [email protected].

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.