Beach sand softens OCTA’s hard armoring proposal for San Clemente’s train tracks

- Share via

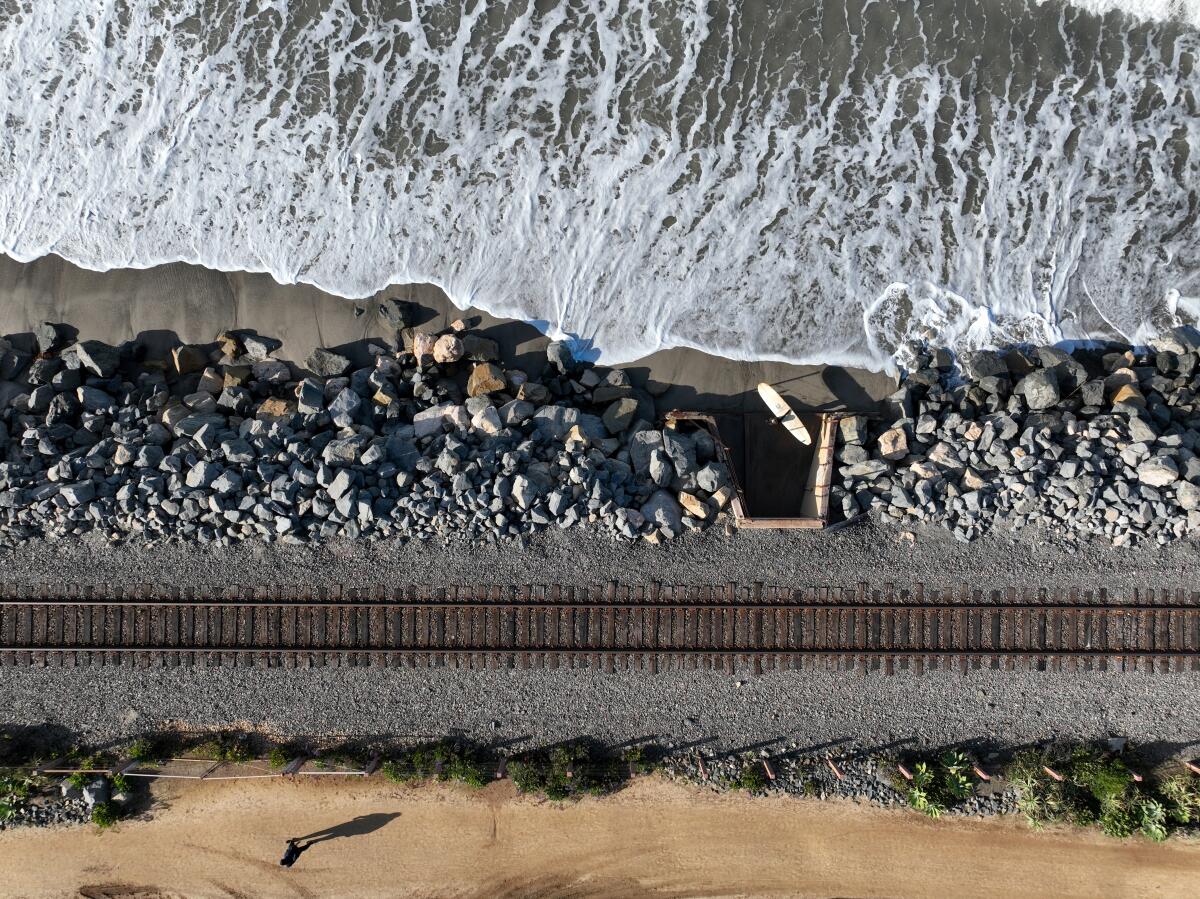

With some beaches in San Clemente so barren from erosion that waves crash up against passing trains, transportation officials are urgently looking to add sand to their plans to protect the troubled rail line.

A sand buffer the size of 285 football fields is now being proposed to shore up the beach town’s coastal segment of a 351-mile rail line that runs between San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles and San Diego.

Darrell Johnson, chief executive officer of the Orange County Transportation Authority, touted a “three-pronged approach” before an April 29 state Senate transportation subcommittee hearing in Sacramento on the so-called Lossan corridor.

“There’s no silver bullet,” he said. “It’s not just walls, it’s not just sand, it’s not just revetment. They all have to be looked at together.”

Landslides in Orange County continue to disrupt the coastal rail line that carries Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner. Is it time to trade stunning views for a reliable route?

Johnson preached the merits of a multifaceted approach again on Monday before an OCTA regional transportation planning committee meeting where members received an update from the agency’s ongoing coastal rail resiliency study.

Caught between crumbling cliffs and beach erosion brought on by urban development, drought and climate change, San Clemente’s train tracks are at crossroads, with some elected officials signaling the need to move the tracks inland as a long-term solution.

OCTA, which owns the rail segment that has been described as the “weakest link” in the Lossan corridor in the aftermath of several devastating landslides, didn’t initially consider sand nourishment as part of its short-term fixes.

Passenger train services have been suspended five times in the past four years, including a months-long interruption after last year’s Casa Romantica landslide.

Two weeks before regular passenger train service resumed through San Clemente in late March following a landslide months earlier that collapsed the part of the pedestrian Mariposa Bridge, transportation officials outlined a $200-million proposal that included half a mile of rubble known as “riprap” and almost a mile of revetment to hard armor the rail line against “imminent threats.”

Plans also called for a half-mile catchment wall near the site of the Mariposa Bridge collapse to protect train tracks from fragile bluffs.

The prospects of adding boulders and retaining walls along San Clemente’s scenic coastline without sand in the plan concerned city officials.

“A big reason that beaches have diminished is actually the rail line,” said San Clemente City Councilman Chris Duncan. “We, unlike almost anywhere else in the country, have a rail line directly on the beach. Sand is the perfect buffer. It’s also the perfect buffer for our homes and our businesses along the coastline.”

The California Coastal Commission and local resident groups also leaned on OCTA to include sand nourishment.

Bring Back Our Beaches, which counts San Clemente Mayor Victor Cabral and Duncan among its listed members, circulated an online petition opposing OCTA’s consideration of hard armoring projects.

The group argued that riprap and revetments contribute to coastal erosion and limit beach access.

With a new dredge site, federal and local officials are hoping the restart can produce beach-quality sand to combat coastal erosion. Questions over increased project costs remain.

After a series of “listening sessions” and meetings, OCTA revised its proposals to include sand nourishment to help address a number of designated “hot spots” along the beach.

“Anytime you see a proposal that did not have sand and now it has 500,000 cubic yards of sand, that’s a good thing,” said Jeff Berg, a spokesman for Bring Back Our Beaches. “It’s much better than where it was before.”

At the Senate subcommittee hearing, Johnson noted that past discussions about hard armoring in March were about potential solutions and not anything final.

With sand nourishment now being considered, San Clemente’s City Manager Andy Hall spoke about the need to have permits expedited.

“What’s going to be really important is that we make the ability to put sand on the beach as easy as putting revetment on the beach,” he said at the hearing. “To do that, I think all of the agencies are going to have to work together.”

Riprap repairs and revetments are quicker to design and construct. A tentative timeline could see such additions underway as early as September.

Based on initial OCTA estimates, sand nourishment could cost between $64 million and $145 million, additionally.

Duncan said that San Clemente would be better positioned to handle that crucial part of building coastal rail resiliency.

“We would prefer that the OCTA allow the city to manage the sand replenishment part of this proposal,” he said. “We can do a lot more sand for a lot less money and we are in a better position to determine where that sand should be allotted and how the project should be carried out.”

San Clemente is currently having sand pumped on the beach south of its pier with a federally supported project overseen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Heavy machinery will return to the city in the fall to finish bringing 251,000 cubic yards of sand for the first phase of the 50-year agreement unrelated to OCTA efforts.

In March, OCTA officials met with the Army Corps to see if the authority could utilize the same contractor and Surfside-Sunset Beach borrow site in North O.C. for future sand nourishment.

“OCTA determined that their best course of action would be to pursue a project on their own, independent from our contract,” said Brooks Hubbard, an Army Corps spokesman. “Since the contractor will remain on the West Coast through 2024, OCTA may be able to capitalize on some cost efficiencies to their project.”

In addition to beach nourishment, the question of sand retention remains.

Under OCTA’s consideration, sand nourishment would be used to widen the beach while covering riprap and revetments.

Supervisor Katrina Foley, who is an OCTA board member, said that approach has been working at Capistrano and Doheny beaches in Dana Point. She also wanted to convene a meeting of sand experts for San Clemente.

Bring Back Our Beaches advocates for what’s called a living shoreline strategy, where plants, sand and rock on coastal berms work as a so-called soft armor solution against erosion.

“You’ve got to have sand and beaches before you can have living shoreline,” Berg said. “We want to see the vegetation that goes with that and can, in some cases, effectively serve the purpose of riprap.”

Suzie Whitelaw, board president of Save Our Beaches and a former oceanography professor at El Camino College, claimed that sand coverage of riprap is vulnerable to being washing away.

During Monday’s OCTA meeting, she aired overall concerns about the agency’s revised proposal, especially the 60,000 to 77,000 tons of rock to reinforce the San Clemente State Beach hot spot.

“It’s still a lot of rock and a little bit of sand,” Whitelaw said.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.