Lorenzo Ramirez, late plaintiff in famed school desegregation case, honored by Orange

- Share via

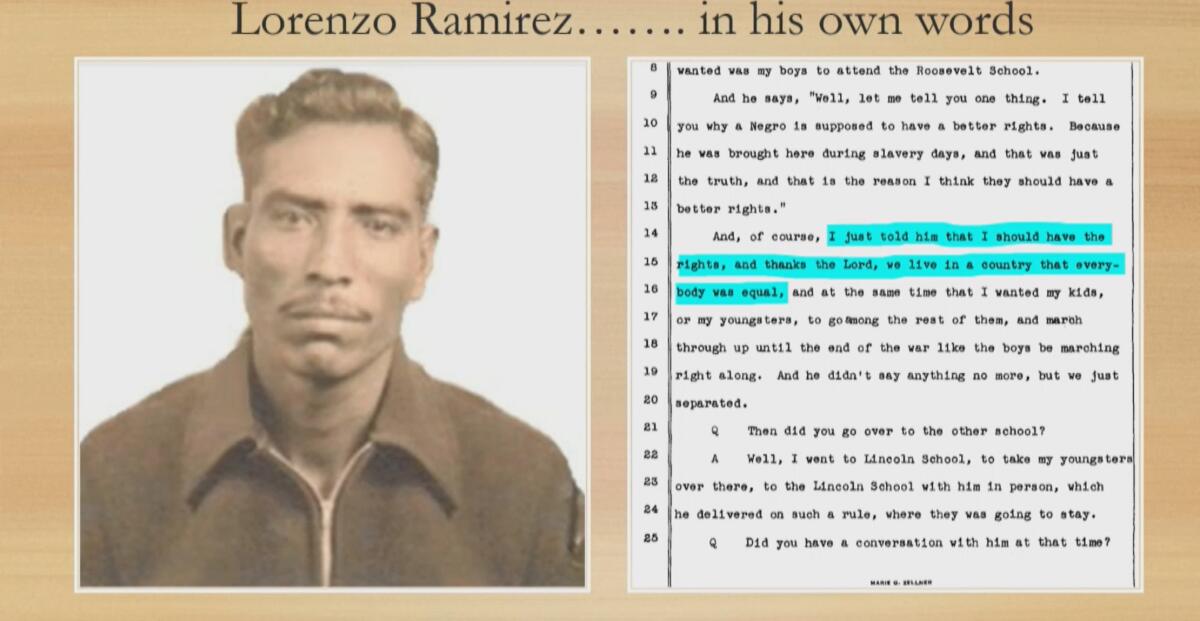

For the past six years, a bust of Lorenzo Ramirez has watched over the Santiago Canyon College library in Orange bearing his name.

Before that, the Orange Unified School District issued a proclamation in 2011 honoring the late Mexican activist’s efforts to bring “educational equity for all of our nation’s children.”

But in the 75 years since an appellate court upheld U.S. District Court Judge Paul J. McCormick’s ruling in Mendez, et al v. Westminster, et al that declared segregated Mexican schools illegal in California, the city of Orange never honored its own historic plaintiff in the case — until its City Council meeting this week.

Orange City Councilwoman Ana Gutierrez presented a proclamation in remembrance of Ramirez’s legacy and in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the landmark civil rights case’s April 14, 1947, appellate court victory.

“For us, as a family, we are just ecstatic,” Michael Ramirez, one of Lorenzo’s surviving sons, told TimesOC. “I just wish my other brothers, Jim and Nacho, who actually went to the segregated school, could be here.”

Gutierrez, a longtime resident of the El Modena barrio who now represents it on council, became aware of the historic case 20 years ago when she transferred over to the Santa Ana Unified School District as a teacher. But it was only recently that Gutierrez gained a deeper appreciation for all of the families involved in the class-action suit.

“Just 2½ years ago, I came to find out who were these ‘et als,’” she said at council. “To my surprise, I found out that one of those five families was the Ramirez family.”

During a presentation, the councilwoman showed a picture of her aunt attending the same segregated Lincoln Grammar School in 1940 alongside Ignacio “Nacho” Ramirez.

“My aunt never shared with me how the schools came to be desegregated,” Gutierrez said. “She, like many of us, didn’t even know the role that this humble man, Lorenzo Ramirez, played in our history.”

Lorenzo migrated to the unincorporated community of El Modena, then known as El Modeno, from Mexico. He attended Roosevelt Elementary alongside white classmates in the 1920s. Lorenzo completed eighth grade and worked in the surrounding ranches. As a family man, he moved to Whittier to work as a ranch foreman in charge of the bracero program before relocating to Gilroy.

When Lorenzo and Josefina, his wife, returned to El Modena in 1944 on account of his ailing father, he tried to enroll his three sons — Ignacio, Silvino (“Jim”) and Jose (“Joe”) — at Roosevelt, as he had once attended the school without incident. But more than just 120 yards separated Roosevelt from nearby Lincoln, where Mexican students attended.

“My father was told that they didn’t have enough desks at Roosevelt,” Ramirez said. “He was forced to have my brothers go to the Mexican school.”

Lorenzo argued with the principal that his sons didn’t speak Spanish in disputing the El Modena School District’s rationale behind segregating Mexican and white students.

“I just told him that I should have the rights,” Lorenzo recounted in trial testimony. “We live in a country that everybody was equal.”

Other families experienced similar indignities at Mexican schools across Orange County. The Ramirez, Guzman, Palomino, Estrada and Mendez families joined together to challenge segregation in Santa Ana, Westminster, Garden Grove and El Modena school districts.

“It wasn’t just any one person,” Ramirez said. “Every family in every district had a different situation.”

What united the families in the class-action federal suit filed in Los Angeles on behalf of 5,000 Mexican school students in O.C. was the common experience of segregation.

The case became officially known as Mendez, et al v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al with Gonzalo Mendez being the lead plaintiff. It influenced Brown v. Board of Education, the historic U.S. Supreme Court school desegregation case in 1954.

But the Ramirez siblings didn’t discover the importance of their own father’s activism until 1998 when Phyllis and her brother Henry came across his name in a history book.

“Our father kept the case away from the family home,” Ramirez said, citing threats his father received. “All of our learning about our father’s activities has come about by our own research.”

After McCormick found in the families’ favor on Feb. 18, 1946, four El Modena trustees and the school superintendent faced a contempt of court citation that same year for failing to integrate its schools.

By the time Ramirez started school at Lincoln Elementary in 1960, Mexican schools became a thing of the past on account of his father’s activism. He was also the only Mexican national plaintiff in the case.

Lorenzo passed away six years later in Riverside, where Ramirez still lives.

His father lived a life of advocacy before and after the Mendez, et al case. As Gutierrez noted in the city’s proclamation, Lorenzo testified in San Francisco before a hearing on the mistreatment of braceros. According to Ramirez’s research, his father also served as president of the Latin American League in El Modena, was active in La Purisima Catholic Church and, in 1953, led the Asociación Progresista Mexicana.

“He was always involved in different things,” Ramirez said. “To get recognized, finally, for that work he did, even behind the scenes, is great.”

In addition to the proclamation, Gutierrez called for a memorial where the schools once stood and a permanent display on the case at El Modena Library. Officials from Rep. Lou Correa, Rep. Katie Porter, state Sen. Dave Min, state Sen. Tom Umberg and Orange County Supervisor Katrina Foley all presented honorifics in Lorenzo’s memory.

The Ramirez family posed with Gutierrez as a portrait of their father hovered above the dais. It was a day in Orange 75 years in the making.

“The kids need to learn this history to know that they do have a heritage here,” Ramirez said. “I’m hoping my father’s legacy inspires kids to further their education.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.