What will Santa Ana do to keep low-income and Latino residents safe from toxic lead?

- Share via

Patricia Flores grew up gardening with her dad in their Santa Ana home.

She didn’t know then that she was being exposed to potentially toxic levels of lead that lie in the soils of low-income and predominately Latino neighborhoods in Santa Ana.

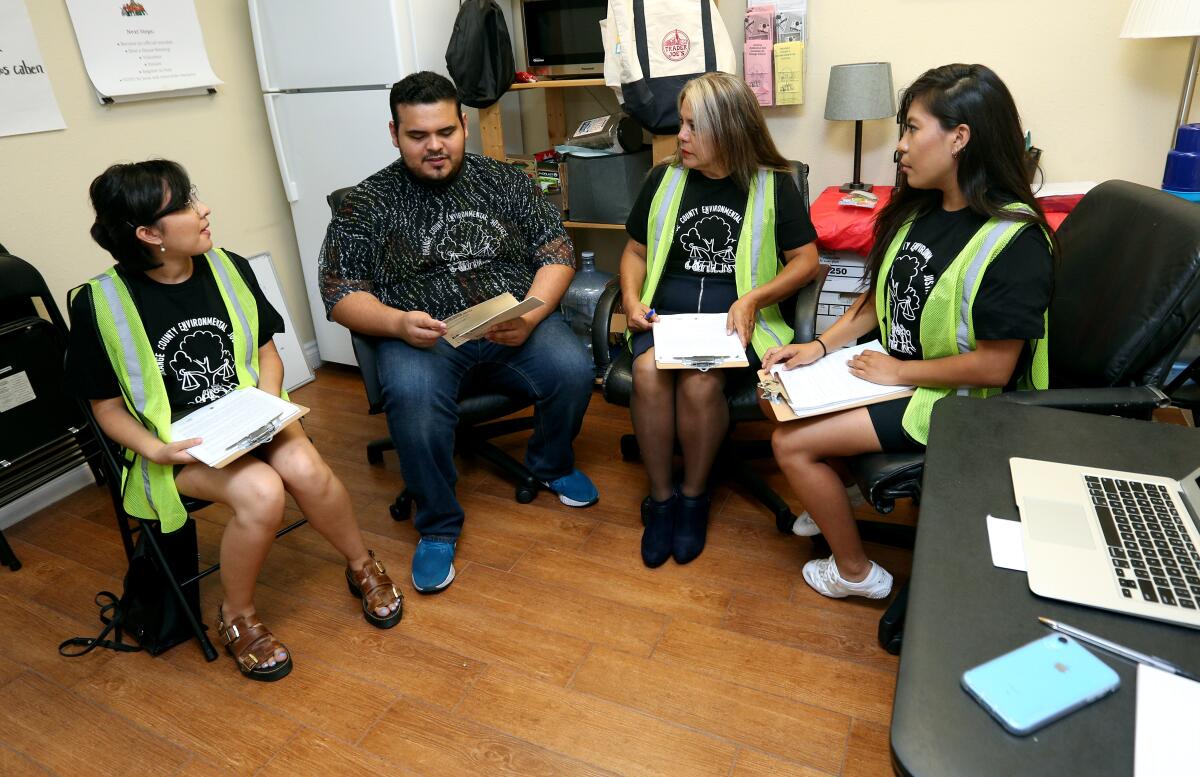

Flores, who now leads the Orange County Environmental Justice nonprofit, said there’s no doubt that the lead has affected her and her siblings’ health.

“It’s a generational issue that’s been affecting us for decades at this point,” Flores said. “It’s an issue that is particularly affecting poor communities of color, and so we see that as a form of environmental racism ... There’s been no initiative to do something about it on the part of the city, the county or the state. So it’s time that something be done to address this issue that’s been affecting our health for generations.”

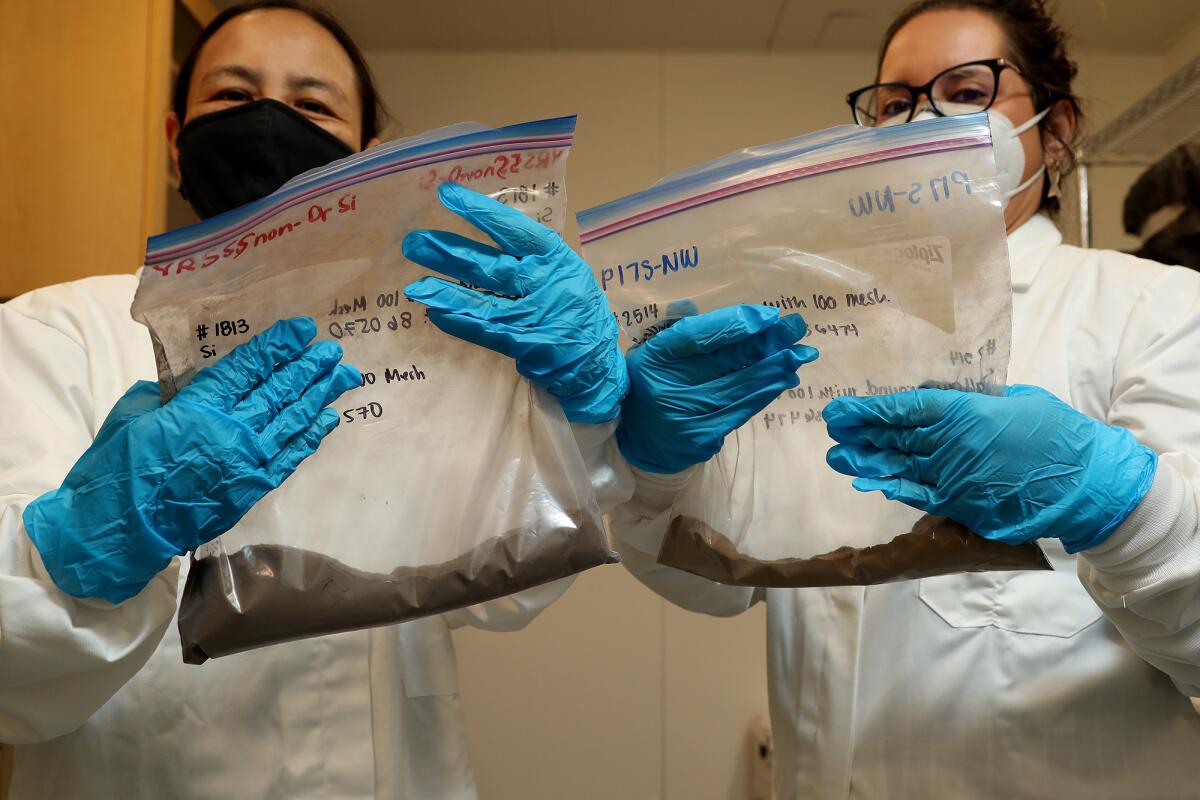

Flores’ nonprofit partnered with UC Irvine researchers and other community members to study the lead levels in Santa Ana soils. After analyzing more than 1,500 soil samples over several years, the coalition determined in 2020 that the samples ranged from 11.4 to 2,687 parts per million, with an average soil sample of 123.1 ppm.

In analyzing how lead disproportionately affects lower-income communities, the researchers found that there was an inverse correlation between income levels and the presence of lead in the community. Soil samples collected in neighborhoods with median household incomes below $50,000 had 440% higher lead levels than communities with a median household income of $100,000, and 70% higher lead concentrations when compared to neighborhoods with median household incomes between $50,000 and $100,000.

That study came after former ThinkProgress investigative reporter Yvette Cabrera published a detailed investigation of the lead crisis in Santa Ana in 2017. For the investigative series, Cabrera found hazardous lead levels after testing more than 1,000 soil samples from homes and other public areas around Santa Ana.

The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment considers anything above 80 ppm in a residential area as hazardous to health. About half of the soil samples exceeded the California safety recommendation. The findings were particularly glaring for children, with researchers finding that neighborhoods housing more than 28,000 children had maximum lead concentrations exceeding 80 ppm, and 12,000 of those children were in neighborhoods with lead concentrations above 400 ppm, the Environmental Protection Agency’s recommendation for play areas.

Children exposed to lead can develop a number of neurological issues, including smaller brain volume, lower working memory and processing speed, more limited perceptual reasoning, poor school performance and asthma. Adults exposed to high levels of lead can suffer cardiovascular issues, renal problems, osteoporosis and cognitive deficiencies.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there is no safe level of lead in the blood of children.

“Even low levels of lead in blood have been shown to affect IQ, ability to pay attention and academic achievement,” says the CDC website.

Hoping to put an end to a longstanding problem for the vulnerable communities of Santa Ana, Flores has been using the findings to press the city and county for a solution. As the city has been updating its general plan over the last year, Flores said the nonprofit saw it as an opportunity to push for soil lead remediation policies to be added to the plan.

Starting in September 2020, the nonprofit has had a series of round table discussions with UC Irvine researchers, the city of Santa Ana and the Orange County Health Care Agency. The group was able to agree on putting policies in the general plan draft, which may be approved by the City Council as early as Dec. 7. Santa Ana spokesman Paul Eakins said that not all the nonprofit’s and UCI researchers’ suggestions were included in the draft.

“The Santa Ana City Council has made the health and safety of our residents, including environmental health, paramount,” Eakins said in an email. “The city of Santa Ana will continue to work to improve our community’s health outcomes under the guidance of the general plan and other city policies and City Council directives.”

The general plan draft states: “Work with Orange County Health Care Agency and local stakeholders including Orange County Environmental Justice and UC Irvine Public Health to identify baseline conditions for lead contamination in Santa Ana, monitor indicators of lead contamination, and measure positive outcomes. Collaborate with these organizations to secure grant funds for soil testing and remediation for residential properties in proximity to sites identified with high soil lead levels, with a focus on Environmental Justice census tracts.”

There are several other items in the general plan draft that are aimed at lead exposure. Another item calls for the city to coordinate with the healthcare agency and community organizations to “strengthen local programs and initiatives to eliminate lead-based paint hazards, with priority given to residential buildings located within environmental justice area boundaries.” The federal government banned consumer uses of lead-containing paint in 1978. Alana LeBrón, a UC Irvine assistant professor of public health and Chicano/Latino studies, said in the past that census data shows the majority of houses in Santa Ana were built prior to that ban. LeBrón partnered with Orange County Environmental Justice on its lead analysis.

Kingspan workers carried out a secretive study to measure exposure to unhealthy air quality while on the job.

The draft also includes an item to train local residential contractors to prevent lead contamination and a general statement to “make homes more healthful by addressing health hazards associated with lead-based paint, asbestos, vermin, mold, VOC-laden materials and prohibiting smoking in multifamily projects, among others.”

Flores is particularly pleased with the city’s commitment in the plan to partner with the O.C. Health Care Agency and other local organizations to increase blood lead testing, outreach, education and referral services.

“So that we think is a good step, because there’s a huge problem in the state of California where the majority of youth are not being properly tested for lead contamination in their blood,” Flores said. “... So it would be helpful to get a better sense of how many youth in Santa Ana are being affected by this issue.”

But Flores hopes the city will follow through with its commitments because general plans are more of a blueprint.

“We think that while there are some good policies in place now, it is not necessarily sufficient to address the full extent of the problem,” Flores said.

Furthermore, Flores doesn’t know how the city will qualify whether an area is in need of remediation because of the differing state and federal lead standards.

“But what’s not clear is at what level because the federal EPA has a different standard than California EPA,” Flores said. “We’re asking for 80 parts per million, since that significantly affects the IQ of children.”

In response to a question about what standard of lead toxicity the city will use, Eakins said that “lead remediation work in Santa Ana is anticipated to be done in collaboration with [the O.C. Health Care Agency] and relevant guidelines.”

When asked if the city was legally required to carry out the environmental justice items in the general plan draft, Eakins responded: “In general, all zoning and land use decisions must be consistent with the general plan. The city is required to carry out the implementation plan associated with each element, subject to the availability of funding, staffing and other necessary resources.”

Undocumented immigrants make up a significant portion of the Santa Ana population, and many are located in the neighborhoods impacted by lead contamination.

Considering many lack access to healthcare, Flores said the nonprofit pushed the city to work with the healthcare agency to ensure access to medical care for this vulnerable population. Flores said that request didn’t move forward.

Flores said the nonprofit also asked for better tenant protections so landlords can’t jack up rent after paying for lead remediation. On Tuesday night, the City Council narrowly approved ordinances for rent control, limiting residential rent increases to no more than 3% per year, and just-cause evictions, preventing landlords from terminating a lease without just cause after 30 days.

Flores also mentioned that the council recently passed a sweeping climate resolution that says the city will investigate and implement policies to limit or prevent exposure to lead and other environmental toxins. However, a resolution lacks the authority of an ordinance.

“So really it’s more useful as a negotiation point,” Flores said.

LeBrón said researchers are continuing to analyze the sources of the lead, whether from past use of leaded gasoline, lead paint or other sources. Researchers are also conducting a historical analysis of land use in Santa Ana to help understand the correlation between elevated lead levels and historical land uses. LeBrón said those analyses could be completed by December or January.

“We’re hopeful that the two analyses that are underway will begin to help us understand who is accountable for the soil levels in the city,” LeBrón said.

LeBrón, who sat in on several of the round-table meetings, criticized the city and Orange County Health Care Agency for initially being dismissive of residents’ concerns about lead following the Cabrera report.

“I’m a public health professor and, honestly, I give our local public health a failing grade for handling resident concerns about lead,” LeBrón said. “They have been incredibly dismissive of residents’ concerns.”

In October 2020, as the city was engaging in talks with Orange County Environmental Justice, former California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s office sent a letter to the city taking issue with the city’s lack of engagement with the community and providing several suggestions of improvement for the city’s environmental justice portion of its general plan draft. The state requires local governments to address environmental justice in their general plans under SB 1000.

“We appreciate the city’s efforts to address environmental justice in its General Plan through inclusion of [environmental justice] policies,” the letter says. “However, we are concerned that the [environmental justice] policies are not sufficient to reduce the unique and compounded health risks to communities as required by SB 1000, nor do they adequately address the specific requirements of SB 1000.”

The letter states that there are 17 census tracts in the city designated as disadvantaged communities, according to CalEnviroScreen, a screening tool developed by the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, a branch of the California EPA. It specifically commended the city for addressing lead contamination in its general plan draft, but recommended that the city strengthen the existing measures and add additional ones to address the lead issue.

The city responded to the letter later that month, stating that “the city’s engagement and outreach efforts to the community and [environmental justice] neighborhoods over the past five years have been substantial and have resulted in a general plan that reflects the voice and the values of the community and our residents.”

However, Eakins said that the city intensified its community engagement this year after receiving the letter with 11 community forums and an online community survey. Eakins also said that the city made changes to the general plan draft to strengthen the lead contamination items.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.