A guide to help you keep track of all the Omicron subvariants

- Share via

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, Americans can be forgiven if they’ve lost track of the latest coronavirus variants circulating nationally and around the world. We’ve heard of the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron variants, but a new Greek-letter variant hasn’t come onto the scene in almost half a year.

Instead, a seemingly endless stream of “subvariants” of Omicron has emerged in the past few months.

How much do they differ from one another? Can an infection caused by one subvariant protect someone from an infection caused by a different subvariant? And how well do COVID-19 vaccines — which were developed before Omicron’s emergence — protect against the subvariants?

We asked medical and epidemiological experts these and other questions. Here’s what they said.

What are the Omicron subvariants, and how do they differ?

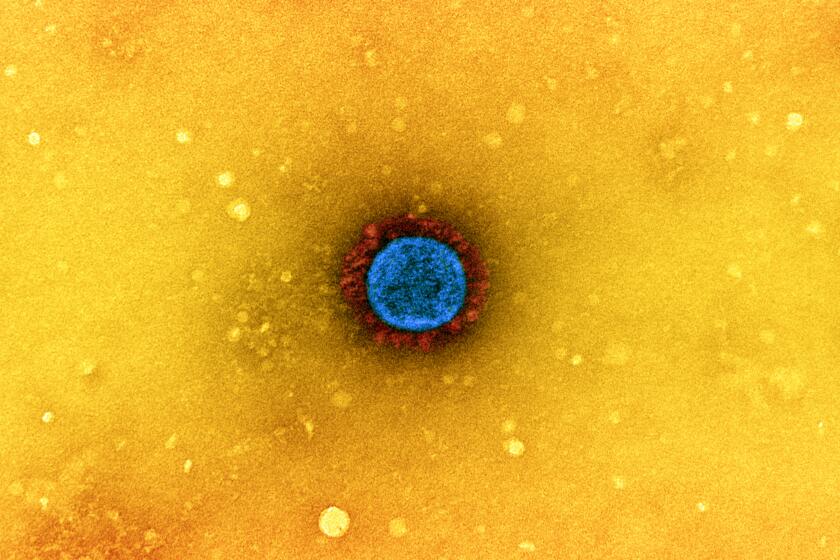

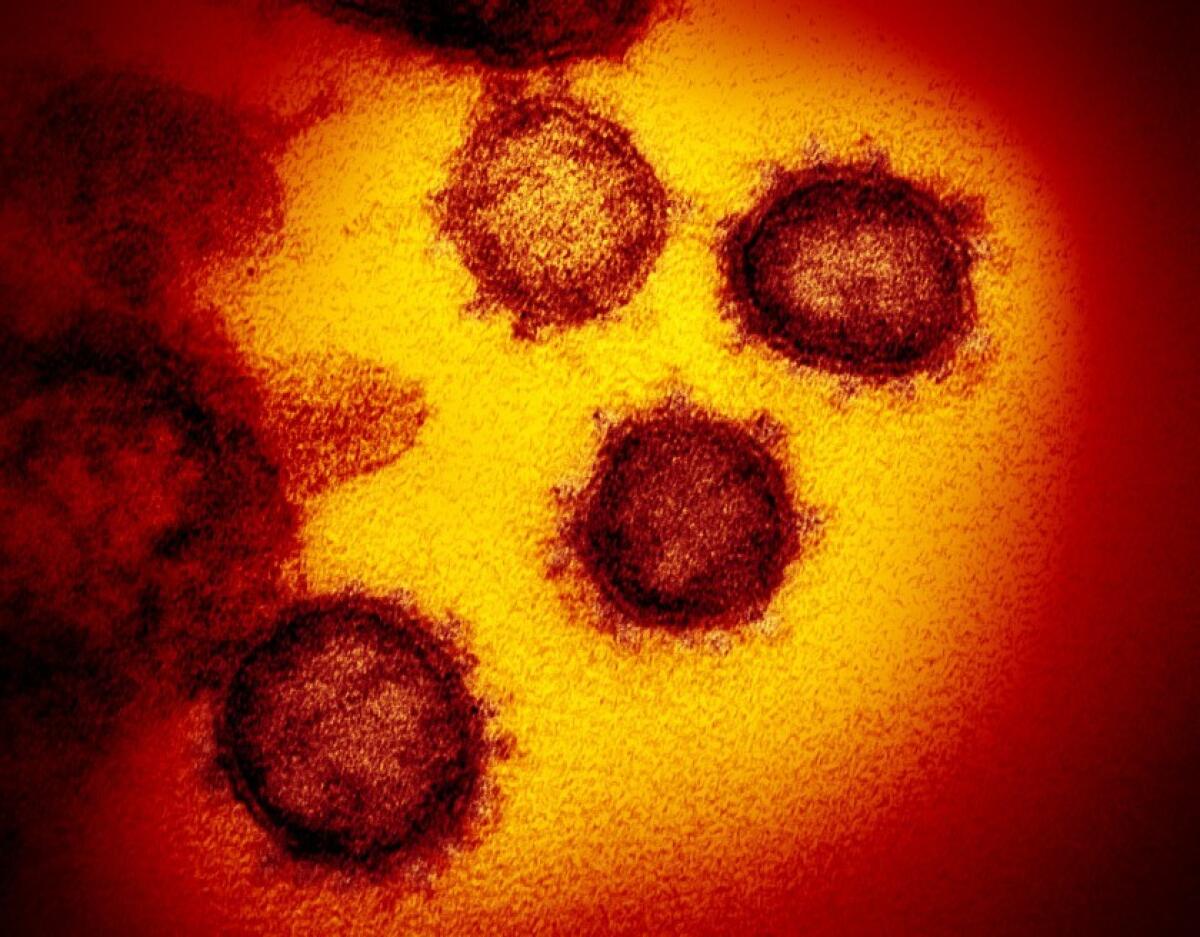

The Omicron subvariants seem like an alphabet soup of letters and numbers. The original Omicron variant was called B.1.1.529. It begat such subvariants as BA.1; BA.1.1; BA.2; BA.2.12.1; BA.3; and the most recent, BA.4 and BA.5.

“They all differ from each other by having different mutations in the spike protein,” which is the part of the virus that penetrates host cells and causes infection, said Dr. Monica Gandhi, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco.

The minor-to-modest mutations in these subvariants can make them marginally more transmissible from person to person. Generally, the higher the number following “BA” in the subvariant’s name, the more transmissible that subvariant is. For instance, BA.2 is thought to be about 30% to 60% more transmissible than its predecessors.

These mutations have enabled subvariants to spread widely, only to be overtaken by a slightly more transmissible subvariant within a few weeks. Then the process repeats.

In the United States, for instance, BA.1.1 was dominant in late January, having overtaken the initial variant, B.1.1.529. But by mid-March, BA.1.1 began losing ground to BA.2, which became dominant by early April. By late April, another subvariant — BA.2.12.1 — was gaining steam, accounting for almost 29% of infections, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (The Delta wave of late 2021 has been a non-factor during this time frame.)

What about the severity of illness?

Fortunately, the illnesses caused by Omicron have typically been less severe than those caused by previous variants — a pattern that seems to hold for all the subvariants studied so far. One analysis from Denmark showed that BA.2 doesn’t cause more hospitalizations than BA.1, Gandhi said.

What accounts for BA.2’s recent success? It’s not due to an ability to evade the protection of COVID-19 vaccines, a new study finds.

Even the most recent subvariants that have been discovered, BA.4 and BA.5, show “no evidence to suggest that it is more worrisome than the original Omicron, other than a potentially slight increase in transmissibility,” said Brooke Nichols, an infectious-disease mathematical modeler at Boston University.

Dr. Dennis Cunningham, the system medical director of infection control and prevention at Henry Ford Health in Detroit, told NBC News that the symptoms from the Omicron subvariants “have been pretty consistent. There’s less incidence of people losing their sense of taste and smell. In a lot of ways, it’s a bad cold, a lot of respiratory symptoms, stuffy nose, coughing, body aches and fatigue.”

If you get infected by one subvariant, will you be protected against others?

So far, with all variants to date, the ability of the virus to evade existing immune protection “is only partial, much like it is for the seasonal flu,” said Colin Russell, a professor of applied evolutionary biology at the University of Amsterdam’s medical center.

While some people who had BA.1 have also gotten BA.2, the initial research suggests that infection with BA.1 “provides strong protection against reinfection with BA.2,” the World Health Organization has said.

With the fast-spreading but less virulent Omicron variant, the coronavirus may finally be cutting humanity a little slack.

“This may explain why our BA.2 surge in the U.S. was not that large as the very large BA.1 surge over the winter,” Gandhi said.

The level of protection can vary depending on how sick you were, with mild cases boosting immunity for perhaps a month or two and recovery from a severe illness granting up to a year.

How do COVID-19 vaccines stack up against these subvariants?

Although the vaccines and boosters aren’t quite as successful in protecting against Omicron as they are against earlier variants, they will generally protect people from severe disease if they are infected by one of the new subvariants.

“We’re steady as she goes with the vaccines we’re using,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and health policy at Vanderbilt University. “I have not seen a single study from the field that shows a substantial distinction between the vaccine responses to Omicron subvariants.”

The vaccines generate cells known as “memory B cells” and have been shown to recognize different variants as they emerge, Gandhi said. The vaccines also trigger the production of T cells, which protect against severe disease, she said.

“While B cells serve as memory banks to produce antibodies when needed, T cells amplify the body’s response to a virus and help recruit cells to attack the pathogen directly,” Gandhi said.

The end result is that a breakthrough infection for a vaccinated individual “should remain mild with the subvariants,” she said.

When the coronavirus attacks the body, the immune system steps up, trying to respond quickly and powerfully enough to stop the virus from running wild.

The wide spread in the U.S. of a relatively mild strain of the virus likely paid dividends by providing many Americans with some immunity, whether or not they had been vaccinated. Research shows that people who had been vaccinated and then were infected had even greater protection than people who had been vaccinated and not infected.

“This family of Omicron could indeed offer a bright side” in the course of the pandemic, Schaffner said.

Looking ahead, vaccine manufacturers are beginning to design vaccines that specifically target Omicron, and some would combine a coronavirus vaccine with a seasonal influenza vaccine in one shot. But these vaccines are in their early stages, and Schaffner said he suspects they won’t be ready and approved by this fall’s flu vaccination season.

Whether such new vaccines represent the next step in the fight against COVID will be up to the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration.

Are any entirely new variants on the horizon?

Experts agreed that the only newcomers in recent weeks have been incremental subvariants — certainly nothing that seems as game-changing as Delta or Omicron were when they first appeared.

“There’s nothing we know of that’s lurking yet, and the surveillance is pretty darn aggressive,” Schaffner said.

Scientists warn that Omicron’s whirlwind spread across the globe practically ensures it won’t be the last worrisome coronavirus variant.

There are estimates that more than 60% of the world’s population has been exposed to Omicron and more than 65% of the world’s population has received at least one dose of the vaccine, Gandhi said, “so I am keeping my fingers crossed the development of new variants will slow with this degree of population immunity.”

Gandhi acknowledged some surprise at how quiet the horizon is right now, but she sees it as a positive development.

“We have now gone five months since hearing about a new variant, which I hope is reflective of increasing immunity in the world’s population,” she said.