Some vaccine experts having second thoughts about rushing to inoculate kids

- Share via

From the earliest days of the pandemic, doctors and public health officials have seen widespread vaccination as the most effective way to stop COVID-19 in its tracks. But a growing contingent of medical experts is now questioning whether that conventional wisdom ought to apply to children.

Their doubts are not borne of conspiracy beliefs, but couched in the carefully calibrated language of risk and benefit. And they’re expected to get a public airing next week as advisors to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ponder a spate of post-vaccine heart problems in adolescents and young adults.

No one is arguing that COVID-19 immunizations for kids should stop altogether. Rather, a debate has erupted over the need to inoculate healthy children as soon as possible and according to the two-dose regimen authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

The vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have been administered safely to millions of adults and been vetted in several thousand adolescents. But neither has been subjected to exhaustive testing in diverse pediatric populations, as is typically required for a vaccine intended for universal use in kids.

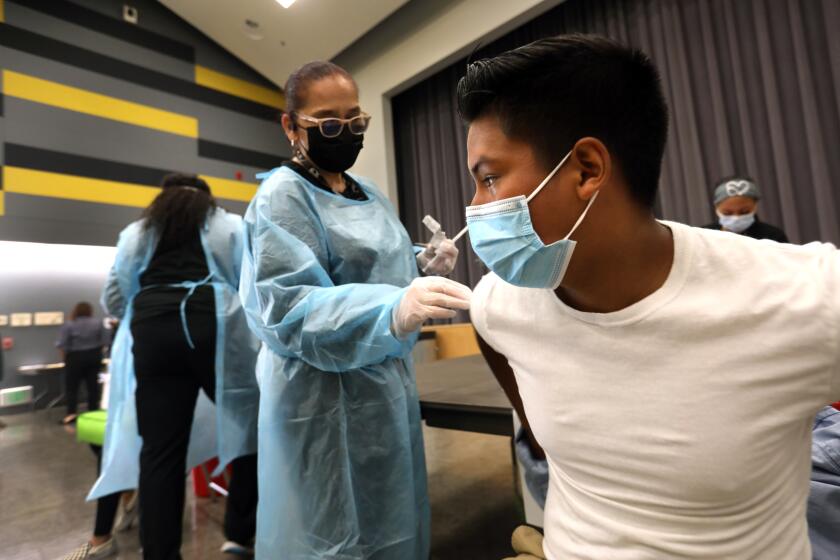

The FDA authorized the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for emergency use in adolescents as young as 12 on May 10. In the weeks that have followed, the safety monitoring systems managed by the FDA and CDC detected dozens of cases of a possible side effect in newly vaccinated teens: an inflammation of the heart muscle known as myocarditis.

The cases typically developed in older adolescents, most of them boys, three to four days after they got a second dose. Virtually all were considered mild, presenting as chest pain and tightness that resolved after treatment with over-the-counter medications. None of the patients appear to have died or suffered serious cardiac malfunction, though it’s too early to know whether they will suffer long-term effects.

As of June 10, the government’s vaccine monitoring systems detected 226 cases of myocarditis or a related condition called pericarditis after vaccination in people younger than 30. Normally, fewer than 100 cases would be expected for this age group, said Dr. Tom Shimabukuro, deputy director of the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office.

More investigation is needed to determine whether the vaccine caused these heart problems or if the timing was merely a coincidence, he said.

A new CDC report on “breakthrough” infections in people who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 finds that just 2% of such cases result in death.

Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and vaccine specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said the reports will give the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices an opportunity to “give people a clinic on relative risk” — as it did after the COVID-19 vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson was linked to a rare blood-clotting disorder in younger women but still deemed safe for use.

Offit said he doubts the myocarditis cases will upend the long-standing certainty that kids should be vaccinated quickly.

“I’d give it to my child in a second,” he said.

Others aren’t so sure. The possibility that children getting the vaccine — especially a second dose — could put their hearts at risk has amplified calls for more debate before parents, schools and others embrace the conviction that all healthy children need to get vaccinated.

It’s not just the prospect of a surprise side effect that has prompted the sudden surge in vaccine caution.

As the pandemic appears to be winding down across the United States and its limited toll on children has been tallied, it’s no longer clear that immunizing children will bring the outbreak to a faster close, said Dr. Martin Makary, a public health expert at Johns Hopkins University.

Makary is urging his colleagues to “think twice” before recommending universal COVID-19 vaccination of healthy kids. Given the data in hand, “there’s no compelling case for it right now,” he wrote this month in MedPage, a website widely read by physicians.

In an interview, Makary said his concerns might be allayed with a more thorough examination of the safety data.

“But no one is thinking like this,” he said. “We’ve converted now from being pro-vaccine to vaccine fanaticism.”

Given the general decline in new infections and hospitalizations, there’s time for a thorough FDA vetting of the vaccines for children and adolescents, Makary said. Even if it takes months, it could wind up protecting more children from harm.

Radiologists have discovered a new side effect of COVID-19 vaccines: They make it more difficult to interpret mammogram results.

The emerging debate threatens to divide a community that’s largely been united by the pandemic.

From the moment that the first COVID-19 vaccine started going into Americans’ arms, one certainty has seemed almost beyond questioning: As soon as enough doses were available, the nation’s children would roll up their sleeves.

There are strong arguments for that position too.

Although it’s clear COVID-19 has largely spared children from severe illness, the CDC says 456 American kids have died of the disease, though that is considered a conservative estimate.

At least 20,000 — and as many as 100,000 — kids have been hospitalized with COVID-19. Indeed, the CDC reports that even as adult hospitalizations declined in March and April, the rate at which adolescents were admitted ticked upward. Nearly one-third were treated in intensive care units, undercutting the argument that severe illness rarely happens in this age group.

COVID-19’s toll on some children also lingers well beyond a bout of infection. As of mid-May, at least 4,018 in the U.S. have developed a condition called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MISC, that frequently appears four to six weeks after a child has cleared his or her infection and typically requires hospitalization.

Myocarditis is common in these very sick children, and roughly 1% die.

If COVID-19 were a disease seen only in children, statistics such as these would galvanize medical professionals and public health officials to find a way to protect them, New York pediatrician Dr. Risa Hoshino wrote in a MedPage commentary sparked in part by Makary’s views.

By any definition, COVID-19 has been an emergency for the nation’s children and the FDA’s emergency use authorization is an “appropriate pathway” for getting vaccines to young Americans, she added.

At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, pediatric cardiologist Dr. Jodie Votava-Smith has seen the wreckage of COVID-19 firsthand, and she has no doubts about the value of vaccinating kids.

In the last month, she has helped treat a patient who developed myocarditis after a dose of vaccine, she said. The child’s symptoms were mild and readily treated with ibuprofen.

Votava-Smith said her assessment of vaccines’ value has been more profoundly shaped by the dozens of children treated at CHLA for serious heart muscle inflammation as a result of having COVID-19. These children were severely ill and now face potentially enduring health effects. The disease was the cause of their misery, she said, not the vaccine.

The mother of two children who are 5 and 7, Votava-Smith said she “can’t wait” to get them vaccinated. “They know they’ll be getting their shot when it’s their turn,” she said.

It is possible for schools to reopen safely in places where coronavirus is under control as long as certain steps are taken to mitigate the risks.

Dr. H. Cody Meissner, a Tufts University pediatrician who advises the FDA on vaccines, said it’s a mistake to evaluate COVID-19 vaccines for children in the same way as it was cleared for emergency use in adults.

“The risk calculation for vaccinating an adult is pretty easy,” he said. When as many as 4,000 adults a day were dying of COVID-19, “even if there was a little risk of vaccine, most people would accept that.”

But for children, he said, “the calculus is a bit different.” Although they seem to contract the coronavirus pretty readily, they’re far less likely than adults to get sick or die. So even if instances of post-vaccination myocarditis are rare, they still change the risk-benefit analysis.

“The data are not sufficient to say that the benefit of these COVID-19 vaccines outweighs the risk in children and adolescents,” Meissner said. “We may get there. But we’re not there now.”

Times staff writer Sean Greene contributed to this report.

More to Read

Updates

8:08 a.m. June 18, 2021: This story originally said the CDC vaccine advisory committee would discuss COVID-19 vaccines for children at a meeting on Friday, June 18. That meeting has been postponed until next week in observance of the new Juneteenth National Independence Day holiday.