Coronavirus: Five burning questions scientists want to answer about the outbreak

- Share via

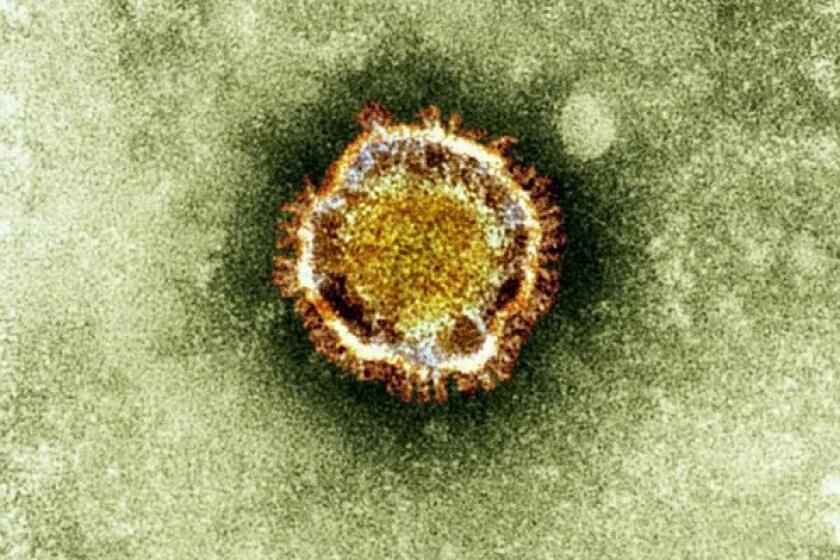

How much do scientists know about the coronavirus spreading through China and around the world? What are they trying to learn as the outbreak expands?

To make decisions about how best to protect the public’s health from the threat of a never-before-seen virus, experts need some answers to a few key questions. Sometimes they have to make decisions without all the answers in hand, or with only partial information. But with more than 6,000 confirmed infections in more than a dozen countries and at least 132 deaths, inaction isn’t an option.

Here are some of the key questions they want answered, and what is known at this time.

Where did the coronavirus come from?

A countless variety of viruses circulate in the animal kingdom, but only a few actually make people sick. Those that do either rear up suddenly or come and go episodically.

This viral knack for emerging (or reemerging) seemingly out of nowhere is based on two things. First, viruses evolve by acquiring new genetic bits from other viruses that share the same host, so new ones constantly appear. Second, a virus that has been around a while needs a “reservoir,” usually a living organism that gives it a friendly place to hang out and replicate until it’s ready to infect humans once again.

Unless you know a virus’ reservoir, efforts to quash it are a little like trying to mop up a flooded bathroom floor before turning off the sink faucet, says University of Minnesota infectious disease expert Michael Osterholm. Eventually, you need to shut off (or at least stem) humans’ exposure to the reservoir if you’re going to prevent new infections.

Any time a “novel” virus appears on the scene, things immediately become much more complicated. That’s certainly the case with the coronavirus from China.

Scientists don’t yet know whether there is an animal reservoir for this novel coronavirus, dubbed 2019-nCoV, and if so, what it might be. Two-thirds of the first 41 patients found to be infected with the virus had been to the same seafood market in Wuhan, capital of central China’s Hubei province, and that may be an important clue. In addition to seafood, vendors at the market (which has since been closed) sold a variety of live and dead animals eaten in China.

Bats were apparently among them, and that’s notable because the flying creatures are a reservoir for other coronaviruses. Indeed, bats are thought to have been the source of the coronavirus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome, which killed 774 people in a 2003 SARS outbreak, as well as the one that led to Middle East respiratory syndrome, which caused 282 deaths in the MERS outbreak that began in 2012.

But this new coronavirus might have come from another of the many animals sold at the market — or from none of them. The fact that several early patients had never been to the market was the first hint that it might have been spreading among humans before Dec. 12, 2019, when Chinese authorities first took note of the infection.

If it turns out that the animals in the market were not the source of the virus, it would mean that researchers are far from closing in on the reservoir for 2019-nCoV. The hunt for its sanctuary will take much more sleuthing by epidemiologists, geneticists, physicians and wildlife biologists.

How does the coronavirus spread?

Once a virus has jumped from its original host to humans and makes them sick, it’s urgent to understand whether, when, how, and how readily the virus will spread directly from one person to another without an animal intermediary.

Those are a lot of separate questions, and getting answers involves a lot of different tools and techniques. But the first step is to painstakingly reconstruct how a single patient — preferably one of the earliest victims — moved through her life after she was exposed and who among her contacts subsequently came down with the same illness. Carefully tracing that chain of transmission will help scientists answer the big-picture questions: How fast does a virus propagate through the population? What actions — travel restrictions, for instance, or school closures — might be necessary to stop the outbreak?

Two studies published last week in the medical journal Lancet describe efforts to reconstruct those early contacts among infected people, and use them to make inferences about how 2019-nCoV spreads. What’s certainly clear is that the virus was moving from person to person early on. In one family of six that visited Wuhan from the Chinese city of Shenzhen, but didn’t go near the seafood market, five became sick after a grandmother and her adult daughter visited a sick baby at a hospital. And after the six returned home to Shenzhen, another relative who had not traveled with them came down with similar symptoms and was found to have been infected with the virus.

In this family, the first signs of illness appeared three to six days after a person was exposed to someone else who was sick. Respiratory distress set in eight to nine days after exposure.

A second study, which analyzed the progression of disease in the first 41 patients, found that about half developed breathing problems roughly nine days after lesser symptoms first appeared. In addition, a little more than 25% of them experienced acute respiratory distress 10 to 15 days after first feeling sick.

If the coronavirus outbreak in China were a Hollywood movie, now would be time to panic. But in real life, most Americans have no need, experts say.

But knowing that human-to-human transmission is happening doesn’t tell you how, exactly, a virus spreads, or how easily. Do you have to share meals and hotel rooms for several days, like the Shenzhen family did? Does wearing a surgical mask help prevent transmission (as may have been the case for the single uninfected family member, who reportedly wore one for most of her time in Wuhan)? How long can the virus survive on a hard surface, like a doorknob, or in the air?

The arrival of rapid, inexpensive genetic-sequencing capabilities has added a further way to trace a virus’ path and understand what kind of contact is necessary to pass it on. Scientists can isolate the virus in people with similar symptoms, and sometimes in people who have been infected but didn’t get sick. By comparing the genetic makeup of those viruses, they can take advantage of the fact that a virus will genetically “shift” as it travels from person to person and use it to make pretty good guesses about who infected whom.

With that information in hand, public health officials can go back and learn more about the contact that resulted in individual cases of person-to-person transmission. Did these people sit a few rows apart from each other on a plane? Or did they share meals, wipe each others’ noses, or have sex?

Experts also want to know the average number of people who will catch a disease from one infected person, a measure called R0 (or “R-naught”). That number for 2019-nCoV is not yet known with any certainty. One of the Lancet studies reckoned that an infected person might spread it to between 1.5 and 3.5 others — a number that would make it much less contagious than measles, which has an R0 of 12 to 18. But scientists are far from having a clear picture of just how, or how readily, this coronavirus will spread.

Can people with no signs of illness spread the virus even if they don’t look sick?

Health authorities urgently want to know whether people who have been infected with the virus, but who don’t yet show symptoms of being sick, can infect others. They also want to know whether those who become infected but don’t get sick at all can nevertheless transmit to others and make them sick.

Answers to these questions could help them determine how far-flung the virus could already be. They could also offer clues as to how long the most restrictive virus-quashing measures — steps like quarantines or business closures — might need to remain in place to ensure that they work.

The unprecedented lockdown of China’s seventh-largest city to cope with the coronavirus outbreak has turned Wuhan into “a ghost town,” says one American who lives there.

Officials from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said there had been “isolated reports” of so-called asymptomatic infection in China and other countries. But Dr. Robert Redfield, the CDC director, said he would draw no conclusions about 2019-nCoV until his agency had reviewed the basis for such assertions.

Meanwhile, U.S. officials are watchful for the appearance of any coronavirus infections that are unrelated to the five known cases already inside the United States. All five of the U.S. patients had traveled to China shortly before they got sick. The emergence of a patient who never left American soil might lead them to a person who had become infected in China and either wasn’t sick when he arrived in the U.S. or did not become sick at all.

Should Americans be concerned? “It could be a catastrophe” if people who appear healthy can easily spread the coronavirus to others, said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University expert on epidemics. “It’s just very, very hard to bring [an outbreak] under control” under such circumstances, he said.

But Dr. Anthony Fauci, who directs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, called for calm. Historically speaking, he said, asymptomatic infection “has never been the driver of outbreaks.”

Who gets sick from coronavirus, and how sick do they get?

It’s important to know this for several reasons. It’s a first step toward divining how big the “tip of the iceberg” is — in other words, how many people must be infected for one person to get sick? That’s an important measure of a virus’ virulence, and a key guide to which people should be most closely watched and most aggressively treated. If there’s a vaccine or treatment that’s in short supply, it could help dictate who should get it first.

It’s also an important factor in determining what public health officials call the “case fatality rate.” To understand the true virulence of an infectious disease, you compare the size of the population that gets it and survives to the size of the group that gets it and dies.

If 2019-nCoV turns out to be as lethal as SARS or MERS, that would not be reassuring. SARS had a 9.5% case fatality rate before it was quickly stamped out in 2003. And MERS has a case fatality rate of 34.4%. Both viruses were (or still are, in the case of MERS) largely contracted in hospitals, so many of their victims were very sick before they became infected.

Among the first group of 41 Chinese patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection, six died. That’s a case fatality rate of close to 15%.

The arrival of the deadly disease worsens the outlook for Hong Kong’s economy and deepens distrust of the city’s government and its rulers in Beijing.

Sometimes, a germ that wreaks havoc in one country sickens few people in another. Such a disparity could be chalked up to differences in the quality of healthcare or the underlying health of the two populations. But it might also be explained by genetic differences in the populations, or to other protective factors. Sometimes one population has acquired a measure of immunity through exposure to related viruses. So China’s experience with the new coronavirus could be quite different than, say, that of the United States.

Unfortunately, the best way to understand who is most vulnerable to a novel virus, and how deadly it is, is for it to circulate widely and affect a large number of people in a number of different countries. But officials would like to stop the new coronavirus before that even happens.

What’s the best way to treat those infected?

Answers to this question are being generated right now. In China, hospital officials who treated the first group of hospitalized patients tried a lot of things. They gave the antiviral drug oseltamivir (marketed as Tamiflu) to 38 of the 41 patients, and nine got steroids, which can amp up the immune response to infection. Those numbers are far too small for anyone to make judgments about treating whole populations of infected people. But clinical trials in China are already underway to understand what works best beyond the “supportive care” of mechanical breathing assistance, fever-reducing drugs and comfort.

At least one of those trials will test the effectiveness of a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir, which is normally used to treat HIV. Fauci said the drug, marketed as Kaletra, is being used on a “compassionate” basis, meaning that it is considered experimental.

Chinese authorities agreed to allow the World Health Organization to send experts to China to assist with research and containment of the coronavirus outbreak.

Meanwhile, he said, American researchers are eager to get their hands on samples of the 2019-nCoV viruses that have been isolated from patients in China. They’d use them to explore designs for new medications that could home in on the virus and selectively kill it or disrupt its replication.

U.S. officials hinted that such sharing might be difficult since China’s scientific and pharmaceutical communities are fiercely competitive and proprietary. But they said much cooperation has already occurred. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar commended the Chinese government for taking a “completely different” posture than it did when the SARS virus appeared out of nowhere in 2003, and its response was slow and secretive.

“We basically just need the best public health people in the world right now” to be seeking answers, Azar said. “We’re ready.”