Triclosan could be really harmful to your gut, and it’s probably in your toothpaste

- Share via

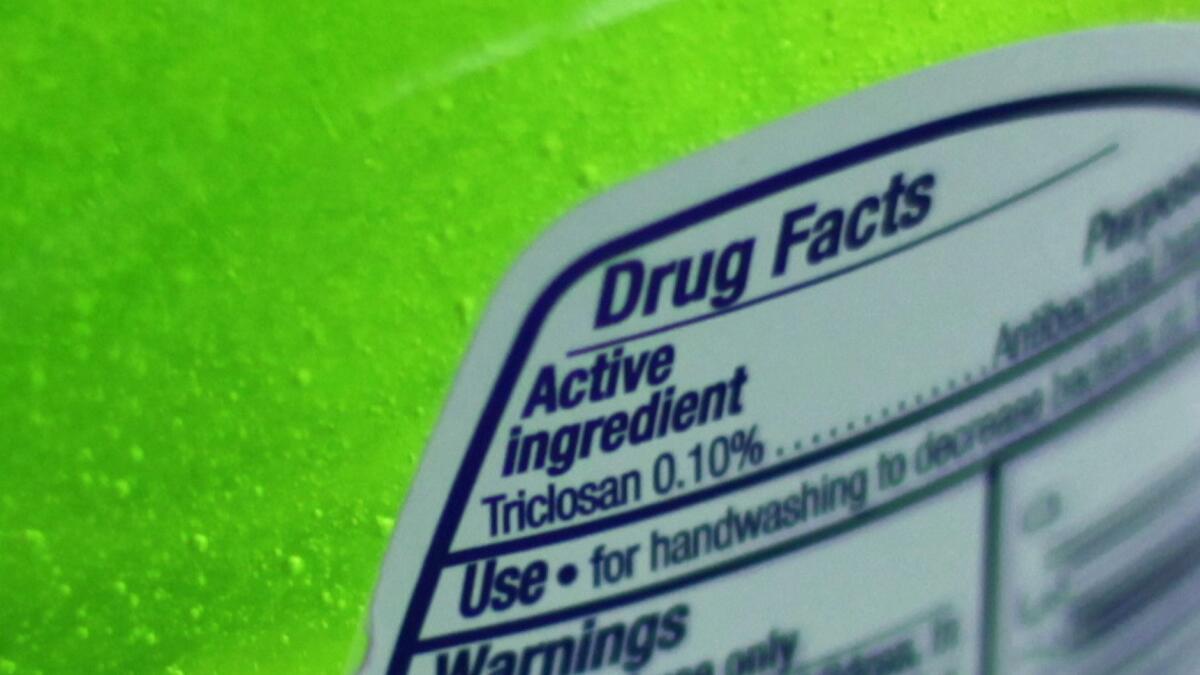

Triclosan, an antimicrobial agent found in toys, toothpaste, cosmetics and more than 2,000 other consumer products, has been found to wreak havoc on the guts of mice whose blood concentrations of the compound are roughly equivalent to a typical level for humans.

One group of mice who were fed a diet laced with triclosan for three weeks ended up with low-grade inflammation of the colon and saw their garden of gut microbes become notably depleted. When researchers chemically induced inflammatory bowel disease in another group of mice, those exposed to real-world levels of triclosan suffered increased damage to the colon and more severe symptoms of colitis than did mice who weren’t fed the chemical.

Finally, in mice made to develop colon cancer, those exposed to triclosan at normal human levels developed more and larger tumors, fueled by the activation of genes known to drive the cancer’s growth. In addition, these mice were slightly more likely to die of colon cancer than their counterparts whose diets and environments were triclosan-free. However, the difference was too small for scientists to say it was more than a statistical fluke.

The findings were published this week in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The study authors, led by Haixia Yang, a postdoctoral food science researcher at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, discovered that the guts of triclosan-fed mice were particularly depleted of Bifidobacterium, a strain that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects.

By changing the gut’s microbiotic population and activating genes that govern inflammation and cancer growth, triclosan “could cause adverse effects on colonic inflammation and colon cancer,” Yang and her colleagues wrote. “Further studies are urgently needed to better characterize the effects of [triclosan] exposure on gut health to establish science-based policies for the regulation of this antimicrobial compound in consumer products.”

Previous research has demonstrated triclosan’s toxicity at doses that would be unusually high for humans, but the new study is among the first to rigorously explore the compound’s safety at more typical levels of exposure.

Triclosan used to be widely used in antibacterial soaps and hand sanitizers marketed to consumers. But the Food & Drug Administration ordered it removed from soaps and hand sanitizers marketed to consumers in 2016. Last December, the FDA declared triclosan and 24 other antimicrobial compounds to be “not generally recognized as safe and effective” for antiseptic products intended for use in healthcare settings as well.

The FDA’s findings gave the makers of antiseptic soaps, rubs and skin preparations until the end of this year to remove triclosan and the other antimicrobial compounds from their products, and most have already done so. But it remains ubiquitous on the U.S. market — an ingredient intended to reduce bacterial contamination of cosmetics, yoga mats and other athletic clothes and gear, children’s toys, kitchenware, and even building materials such as carpeting and paint.

It would fall to the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate the use of triclosan and related antimicrobial agents in consumer goods where no health benefit to the consumer is claimed. Under EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, the agency has been focused on rolling back regulations rather than expanding them.

Meanwhile, triclosan is routinely still used in many toothpastes — with the FDA’s blessing — since it has been found to prevent gingivitis. Researchers have found evidence it settles and accumulates in household dust, extending humans’ exposure.

Triclosan appears to be readily absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. While humans clear most of it quickly, there is growing evidence that traces of the compound accumulate. And its health effects have come under mounting suspicion.

At high doses, triclosan is associated with a decrease in the levels of some thyroid hormones, at least in animals. Other studies have raised concern that exposure to triclosan increases the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance to antibiotics. Researchers are also exploring whether long-term triclosan exposure increases risk for skin cancer.

Last June, 200 scientists and medical professionals signed the Florence statement, calling triclosan and a related agent, triclocarban, “environmentally persistent endocrine disruptors that bioaccumulate in and are toxic to aquatic and other organisms.” The group called for “greater transparency” in their use, adding that “they should only be used when they provide an evidence-based health benefit.”

Northwestern University environmental engineer Erica Marie Hartmann, who was not involved in the new study, said the work was “very thorough.”

“These researchers have drilled down and said, ‘We think this adverse effect is mediated by gut microbiome,’” she said.

Since the FDA has called its routine use into question, conducting trials of long-term human exposure to triclosan might be ethically problematic, Hartmann added.

“But I think it’s fair to say, it’s possible to draw analogies,” she said. “Even at very low levels of exposure, we still see these adverse health outcomes. … This doesn’t make me feel any more comfortable about triclosan in toothpaste.”

MORE IN SCIENCE