Scientists identify potential birth control ‘pill’ for men

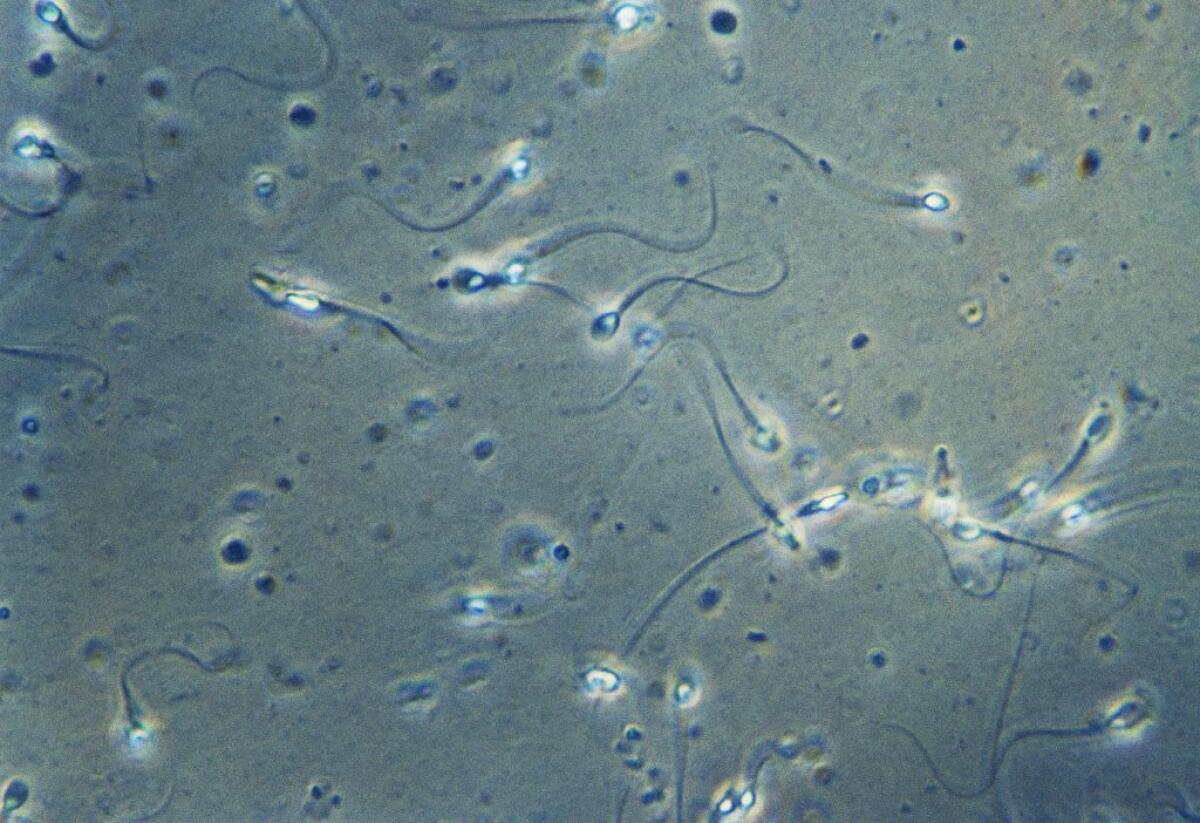

Sperm have a protein that no other cells have. Scientists say its discovery could help them develop a male contraceptive.

- Share via

Two drugs that help suppress the immune system in organ transplant patients may have a future as the long-sought birth control “pill” for men, new research suggests.

The drugs – cyclosporine A (also known as CsA) and FK506 (also known as tacrolimus) – are given to transplant recipients to reduce the risk that the patient’s body will reject its new organ. They work by preventing the immune system from making a protein that would otherwise mobilize T-cells to attack. Specifically, they do this by inhibiting an enzyme called calcineurin.

By studying mice, researchers in Japan identified a version of calcineurin that is found only in sperm. This particular version contains a pair of proteins, called PPP3CC and PPP3R2.

To figure out what these proteins do, the researchers created male mice that were unable to make the PPP3CC protein (and thus produced less of the PPP3R2 protein). Then they studied the “knockout” animals to see how they were different from regular mice.

The knockout mice still had sex with female mice, but the females didn’t become pregnant. The absence of PPP3CC must be making the males infertile, the researchers figured. So they set about figuring out why.

They found that sperm from the knockout mice were able to reach the part of the ovary where eggs are usually fertilized. Although the number of sperm that completed the journey was lower than in regular mice, it wasn’t low enough to explain the infertility.

So they performed in vitro fertilization using sperm from the knockout mice. The sperm were unable to fertilize an egg as long as the egg was covered by its usual layer of cumulus cells.

But it wasn’t the cumulus cells that were the problem. In further tests, the researchers found that the sperm could make their way through these cells and bind to the zona pellucida, or ZP, the membrane that surrounds the egg. But that was as far as they could go.

What kept the sperm from getting through the ZP? The knockout sperm were able to move at the about same velocity as the regular sperm, the researchers found. However, the knockout sperm were deficient at something called “hyperactivation.” This is a particular type of movement that requires the sperm’s whip-like tail to beat back and forth with extra force.

Still, the Japanese researchers wanted to know more. They determined that the tails of the knockout sperm moved with the same “beat frequencies” as regular sperm. The problem was that the part of the sperm that connects the head to the tail was too rigid. That made the entire sperm cell too inflexible to move with enough force to penetrate the ZP, the researchers concluded.

To make sure this was the true bottleneck, they used IVF to see whether knockout sperm could fertilize eggs once the ZP was gone. They could, and the fertilized eggs developed all the way to term.

Finally, the research team gave the immunosuppressant drugs to regular mice, to see whether their sperm would turn out like the sperm of the knockout mice.

The drugs had no effect on mature sperm cells, which were just as flexible as ever, but worked better on sperm that were still developing.

Regular male mice that got either CsA or FK506 for two weeks became infertile, because the middle part of their sperm was rigid. Further tests showed that it took only four days for FK506 to render the mice infertile, and five days for CsA to do the same.

When the mice stopped taking the drugs, their fertility returned after one week.

“Considering these results in mice, sperm calcineurin may be a target for reversible and rapidly acting human male contraceptives,” they concluded.

The study, led by Haruhiko Miyata of Osaka University’s Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, was published Thursday in Science.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

ALSO:

Wealthy L.A. areas use far more energy than poor ones

Salton sea faces catastrophic future, toxic dust storms, officials say

Asteroid that killed the dinosaurs had help from volcanoes, study says