For high school football players, just a season of play brings brain changes

- Share via

Without sustaining a single concussion, a North Carolina high school football team showed worrisome brain changes after a single season of play, a new study has shown.

A detailed effort to capture the on-field experiences of 24 high school football players showed that, at the end of a single season of play, teammates whose heads sustained the most frequent contact with other moving bodies had the most pronounced changes in several measures of brain health.

The new research findings, presented Monday at a meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, are a key first step in discovering how the developing brain responds to the repeated blows that come with youth football. Researchers underscored that they don’t know yet whether the young brains they studied might recover completely in the off-season, or whether their expected developmental trajectory might be knocked off-course by the impacts.

Only more long-term research on a broader swath of players will tell, said the new study’s authors, who come from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Those studies are already underway. Across the country, neuroscientists and sports-injury experts have lashed together their efforts to conduct brain-imaging research on participants in youth contact sports. In the course of the high school football season just completed, the resulting consortium conducted studies that will supplement the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center findings.

“It’s important to understand the potential changes occurring in the brain related to youth contact sports,” said Elizabeth Moody Davenport, a postdoctoral researcher at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who led the latest study.

“We know that some professional football players suffer from a serious condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE,” said Davenport. “We are attempting to find out when and how that process starts, so that we can keep sports a healthy activity for millions of children and adolescents,” she added.

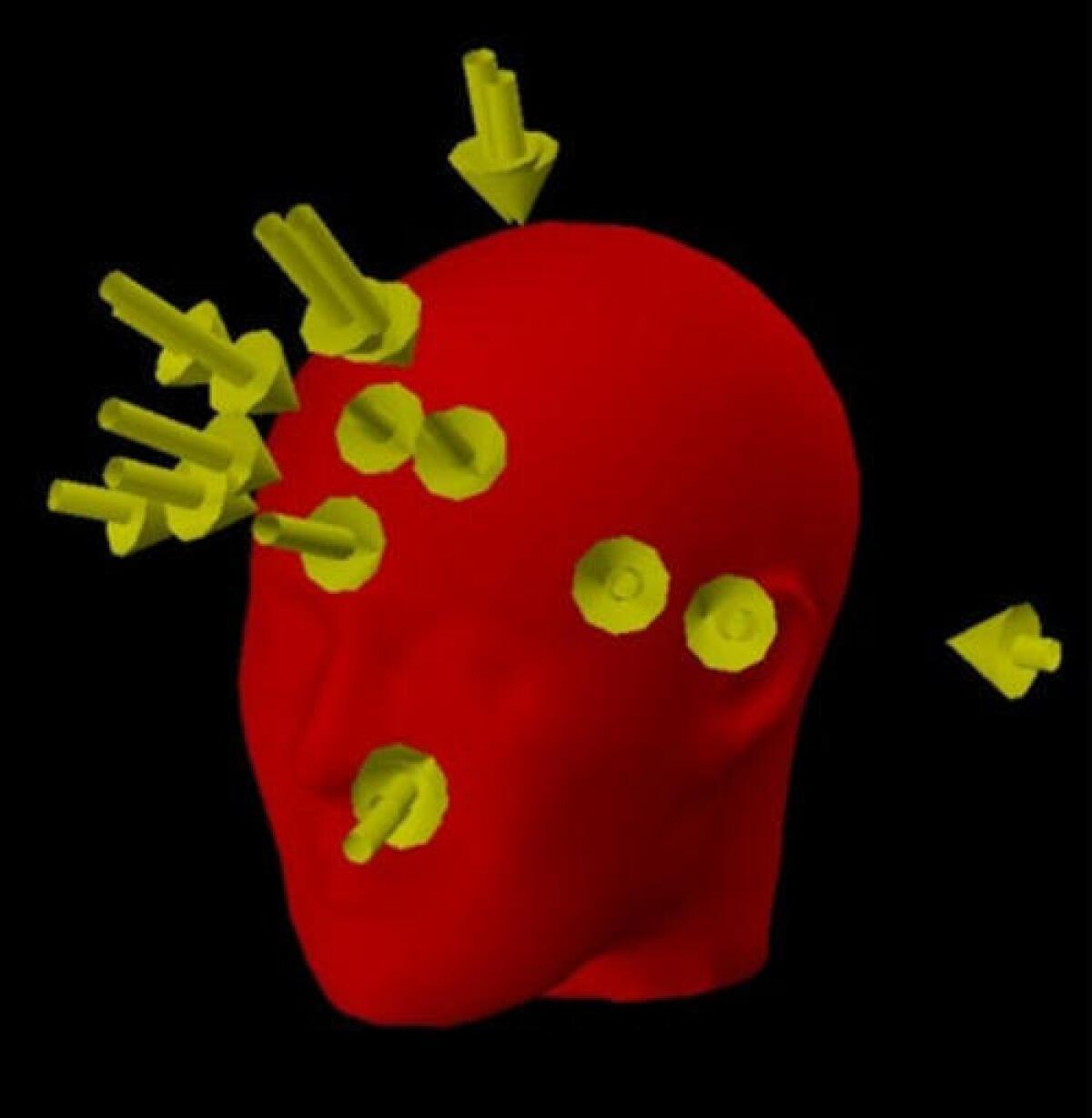

In the study presented Monday, researchers focused on 24 members of a single high school football squad, wiring up each player’s helmet with six accelerometers. During practices as well as play, those sensors gathered detailed data on the location, strength of impact and direction of any blows to a player’s head.

Called the Head Impact Telemetry System, or HITS, this suite of sensors allowed researchers to record exactly how many and what types of blows to the head a given player had over the course of a season, as well as how forceful they were. Data from the helmets were uploaded to a computer for analysis.

The study’s 24 subjects were 17 years old on average. None had ever had a diagnosed concussion, and no concussions were seen in the course of the team’s season.

When they have detailed before-and-after brain imaging studies, researchers can use the HITS results to infer links between certain kinds of brain impacts and observed brain changes.

Before the season began as well as after it ended, the North Carolina players underwent brain-imaging scans that measured the density of key brain structures and analyzed certain patterns of electrical activity generated by their working brain cells.

In two different kinds of specialized MRI scans, scientists sought to measure the integrity of the brain’s “white matter” — the bundles of insulated wiring that carry electrical signals both among cells and between groups of cells on either side of the brain’s two hemispheres. Earlier research has suggested that blows to the head that cause the brain to move side-to-side in its skeletal casing — such as those sustained by boxers — can twist and shear these bundles of connective tissue and disrupt their ability to conduct electrical signals efficiently.

A second type of scan, a magnetoencephalography (MEG) scan, recorded and analyzed the magnetic fields produced by brain waves. Among the many patterns they might listen for, researchers were attuned to Delta waves, a form of slow-wave activity described by Davenport as “a type of distress signal” emitted by the injured brain.

The scans showed that the condition of the brain’s white matter was most affected in players whose helmets had recorded the most linear acceleration — the kind of direct frontal hit a receiver might get when returning a kick, or that a lineman might sustain repeatedly when lunging forward on every play.

Changes on the MEG scan were most often seen in players whose helmets showed they had sustained the most rotational impact. In rotational impact, the brain twists within the skull, usually in response to a sideways impact.

Boxers, who receive punches to the side of the head, often show the effects of rotational impacts. In football, the brain of a quarterback or ball-runner who is tackled laterally will likely withstand strong rotational forces.

Davenport said such results “demonstrate that you need both” brain imaging that measures changes in the brain’s structure and imaging that detects changes in its workings. Different kinds of brain changes are linked to “very different” kinds of impacts, she noted. And as researchers begin to recognize whether long-term behavioral effects — say, depression, memory loss or movement disturbances — come with certain brain changes, they can begin to protect players accordingly.

As important, given the North Carolina team’s concussion-free season, is that it might be important to have both types of brain imaging to discern what effects repeated sub-concussive blows to the head might have, Davenport and her colleagues said.

Mounting evidence already suggests that sustaining multiple concussions puts a person at higher risk of later depression, memory loss and other neuropsychiatric problems. But researchers suspect that even when they don’t result in a concussion diagnosis, repeated blows to the head may be harmful as well. More, and more sensitive, tests will help reveal whether that is so.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.