Star-shaped drug dispenser stays in gut to deliver medication for weeks

- Share via

Wrought in metal and wielded by a ninja, one star-shaped device can deliver swift, silent death. Now, researchers have unveiled a star-shaped device designed to deliver health for weeks at a time.

A team of Boston-based engineers and physicians on Wednesday demonstrated a first: a multi-pronged drug-delivery mechanism capable of withstanding the tumultuous and corrosive forces that prevail in the human gut for as long as two weeks.

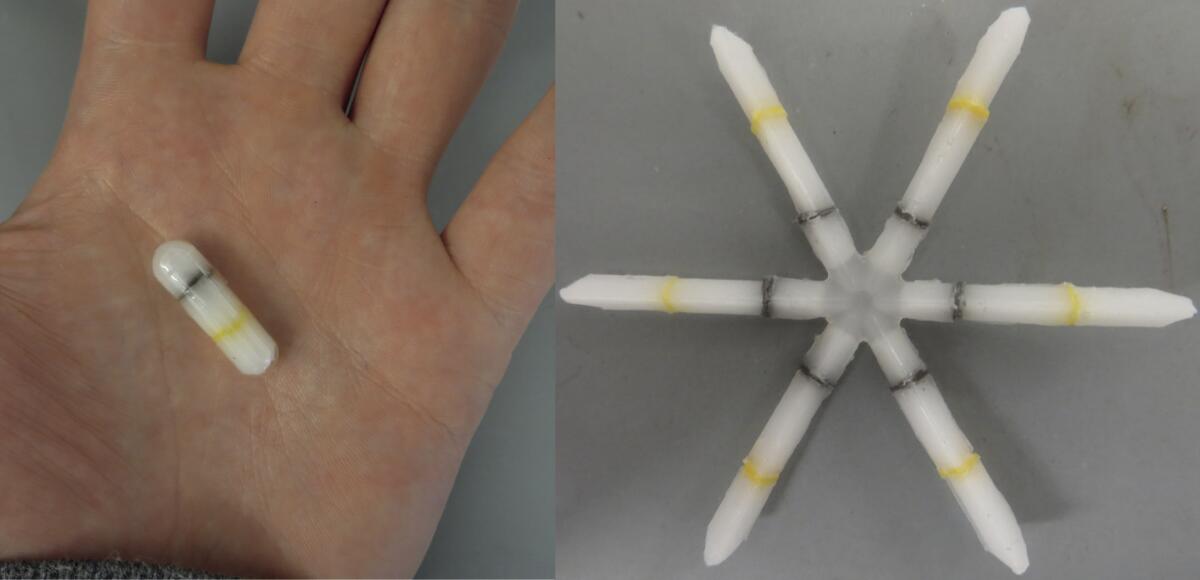

Wrought in polymer materials and packed into a gelatin capsule, the device unfurls its six arms once it has made its way to the stomach. And then, remarkably, it sits there, without impeding the forward progress of other comestibles. While food and drink moves on, the drug-delivering star stays put and continues to release steady doses of medication.

As reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the device safely delivered the antiparasitic drug ivermectin for ten days in the bellies of Yorkshire pigs, whose stomachs and intestinal tracts look and behave very much like those of humans. Dogs, too, were used to test the safety and effectiveness of the new device.

And human trials are to begin next year, according to the inventors of the device.

The device is the easy-to-swallow answer to a long-standing problem: While many drugs must be taken daily (or more often) to be effective, humans are notoriously poor at taking such medications as directed on schedule.

In developed countries such as the United States, half of patients don’t adhere to medication regimens that must be kept up for more than a couple of days. Despite the availability of effective drugs, people get and stay sick and develop complications that can kill.

Each year in the United States, this problem, called treatment non-adherence, is responsible for $100 billion in health care costs.

In rich countries, injections, pumps and implanted devices can deliver drugs continuously, but they can be expensive and intrusive. In developing countries, the cost and complexity of such drug-delivery mechanisms can put them out of reach.

Pills deliver medicine the cheap and easy way. But for medication that must be taken daily, pills face a problem: The human gut is made to move things along quickly. To ensure nothing stays in the stomach for longer than a day, gastric acids break down anything swallowed, and powerful muscular contractions move the result through the digestive tract.

Medication designed to dissolve slowly in the stomach won’t stick around around long enough to deliver its healing payload for more than a day.

In the team’s early tests, pigs and dogs easily swallowed the device bound up in a gelatin capsule. Once in the stomach, the six arms of the device deployed, and the polymer matrix in which the medication was embedded ensured that medication was released slowly and evenly. The device’s prongs helped to keep it from passing onward for ten days. And once the medication was released, the device dissolved and was passed out of the animals’ digestive systems easily.

“This really opens up a new way for patients to start taking their medicine, and to think about taking their medicine and treating their disease,” said Dr. Andrew M. Bellinger, a researcher at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and a developer of the star-shaped device.

Ivermectin, the medication dispensed by the device in the first round of tests, is an antiparasitic drug used by humans the world over to combat both river blindness and malaria.

When a malarial patient takes 24 tablets of ivermectin over three days, it’s highly effective at killing the Plasmodium parasite transmitted in the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito. But like many medications that must be taken over several days, ivermectin is often ineffective because humans miss doses and don’t get enough of the drug to kill the parasites.

Missed medication is a problem not only in the treatment of malaria, which threatens nearly half the world’s population in any given year. Bellinger and his collaborator, Dr. Giovanni Traverso, worked with chemical and mechanical engineers, as well as pharmaceutical researchers and physicians, to devise a system that could be taken by mouth and would withstand the gut’s powerful forces while letting other food pass through normally, deliver medication evenly over several days, then dissolve and disappear without incident.

Traverso, a gastroenterologist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, underscored that the device’s ability to stay put while letting food and liquid pass through the stomach was a key challenge. The device’s six-pointed shape was an important design innovation in keeping it in place, Traverso said. And to ensure that the device would not dump medication too quickly if it passed prematurely into the small intestine, researchers had to design an “abort” mechanism into the device.

“People have been trying to develop this for decades,” said Bellinger. To test its feasibility, the team tried it in 300 experiments involving Yorkshire pigs and in experiments involving 100 dogs.

If the drug-delivery device proves safe and effective in humans, Bellinger and Traverso expect it could be useful in delivering a wide range of medications for diseases in which patient non-adherence is a problem. He said the device might keep patients on track who take medication to suppress or rev up their immune systems, and for neuropsychiatric conditions, cardiovascular diseases and addiction.

It also could dramatically improve treatment of diseases that plague the developing world, such as malaria and tuberculosis. The development of the device was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE