How plants can provide clues about the spread of ancient civilizations

- Share via

Indiana Jones may have found a few more lost temples if he’d known a thing or two about plants. By mapping the distribution of tree species with known archaeological sites in the Amazon basin, scientists have discovered that humans shaped the makeup of the Amazon forests over thousands of years.

The findings, described in the journal Science, highlight the complex relationship between pre-industrial humans and the ecology of the environments they lived in — and may offer archaeologists a new tool with which to look for undiscovered human settlements.

The rainforests of the Amazon — those that have not been chopped or burned down to make use of lumber or clear land for crops — are largely seen as “pristine” terrain, largely untouched by humans. But before Europeans arrived in the Americas, indigenous peoples had been domesticating (or partly domesticating) species that were useful for food or other resources for thousands of years. Surely they had left some mark on the makeup of their environments, even if their settlements were hidden from sight.

“I was wondering if we can detect in the forest effects of past societies — and how we can use the species in the forest to really see these effects,” said lead author Carolina Levis, a PhD student in ecology at Brazil’s National Institute for Amazonian Research and Wageningen University and Research Center in the Netherlands.

Using 1,170 forest plots in the Amazon Tree Diversity Network, a data-sharing collaboration between more than 180 researchers to track tree diversity in the Amazon Basin and the Guyana Shield, the scientists identified 4,962 species, of which 227 were “hyperdominant,” or extremely abundant.

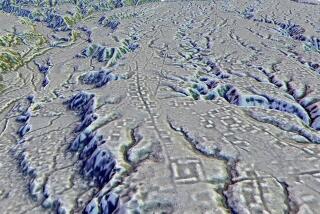

They then took 1,091 of those forest plots in nonflooded lowland Amazonian forests and layered them on top of a map of more than 3,000 archaeological sites in the region. These sites include pre-Colombian settlements; earthworks such as mounds, causeways, raised fields and terraces; and rock art, including paintings and petroglyphs.

The researchers focused on 85 tree species that Amazonian people are known to have cultivated over several thousand years, including Brazil nut, cacao and acai. Twenty of those species were “hyperdominants” — which was about five times higher than would be expected by chance. And the closer these cultivated plants were to an archaeological site, the more abundant and more diverse they were.

These forests, then, are not just an ecological resource to be treasured and preserved — they’re also a part of cultural heritage, Levis said. In fact, following the domesticated plants might allow scientists to find undiscovered archaeological sites.

“It would be very cool to use the plants to detect new sites because archaeological sites are sometimes difficult to find in the forest,” she said. After all, she added, “many of these groups are not there anymore to tell their story.”

That’s all the more reason to preserve these ecosystems, many of which are under threat from deforestation for lumber or to make way for plantations of exotic crops such as soybeans, she added.

Many of the trees being chopped or burned down have been useful to humans for thousands of years, and are still in use by local populations. And those pre-Columbian peoples managed to cultivate these plants within the forest ecosystems, rather than completely destroying them.

“We should learn more from this type of food production that people used in the past that didn’t lead to widespread deforestation,” she said.

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Even bumblebees can learn to use tools, scientists show

Are restrictions on the ‘abortion pill’ politics or science?

Scientists study ways to preserve world heritage sites damaged in armed conflicts