Africa’s baobab trees can live for more than 1,000 years, but many of the oldest and largest are dying

- Share via

The oldest and biggest angiosperm trees in the world, the African baobabs, are dying or already dead, an international team of scientists has found.

The scientists added that the spate of deaths, described in the journal Nature Plants, might be the result of a changing climate – though they say that research needs to be done to confirm or deny that idea.

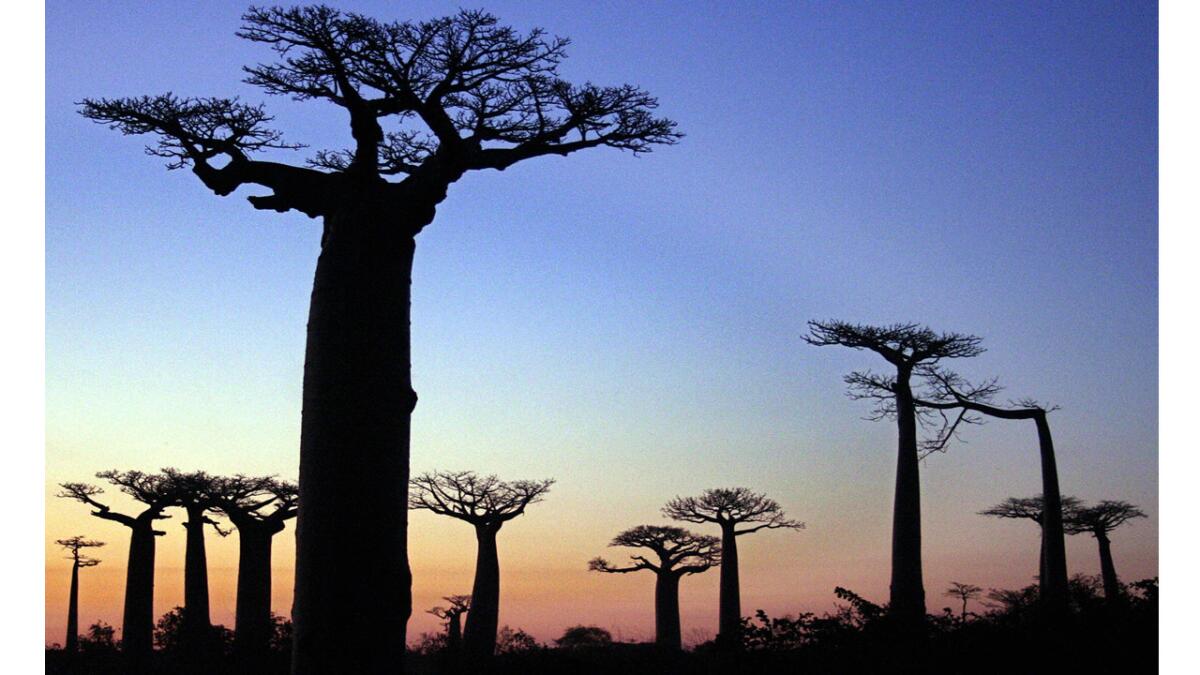

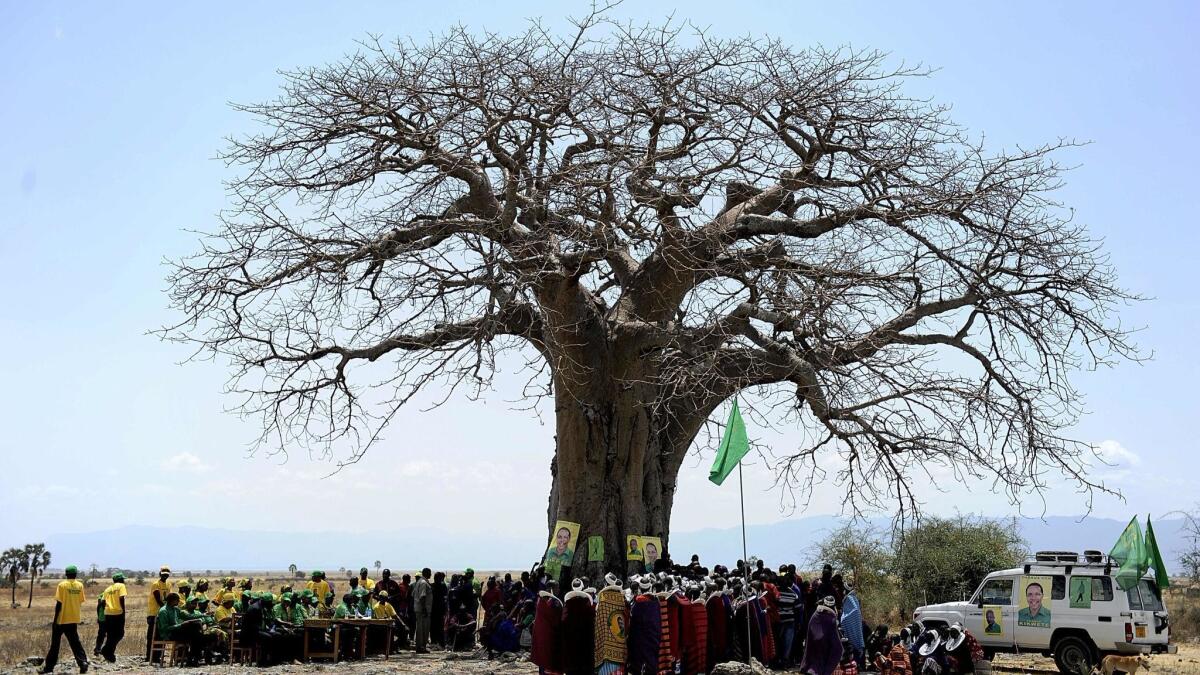

The baobab known as Adansonia digitata L. is an icon of the African savannah. With wide, cylindrical trunks and gnarled branches, the trees appear to have been yanked out of the ground, flipped over and shoved back in, roots in the air. These giant plants are the largest and longest-living angiosperm (or flowering) trees today, with some individuals surviving for close to 2,000 years.

Baobab trees have been nicknamed the “tree of life,” but they could just as well be called the giving tree: The leaves and fruit of many species also provide nutritious food, their bark can be made into rope and cloth, their wood can be harvested for hunting and fishing tools, the seeds hold an oil that’s used in cosmetics, and their broad, occasionally hollowed-out trunks can be used for shelter.

“Baobabs are particular trees, with unique architectures, remarkable regeneration properties and high cultural and historic value,” lead author Adrian Patrut, a chemist at Babes-Bolyai University in Romania, said in an email. In addition, “they play an important role in carbon sequestration and create a distinct microenvironment. Baobabs are the oldest and largest angiosperms and the impact of their loss would have profound consequences.”

But until recently, he said, much about these trees was not known with confidence — which is why in 2005 an international team of researchers embarked on a project to study their structure, growth and age.

Patrut and his colleagues argue that big African baobab specimens always have multiple stems. Although baobabs typically begin growing as single-stemmed trees, they produce new ones over time, developing increasingly complex structures, the scientists say. These multiple stems can start to trace out a ring-shaped architecture, containing an empty space.

These structures defy ring-counting, the traditional method of age-dating trees, Patrut said. So the scientists instead used accelerator mass spectrometry to perform radiocarbon dating on samples from some of the largest, oldest trees in southern Africa.

The researchers found that since 2005 eight of the 13 oldest, and five of the six largest, African baobab trees have either died or had their oldest parts or stems die. This includes Panke, a sacred baobab in Zimbabwe that was estimated to be about 2,450 years old, with a 25.5-meter-wide trunk and a height of 15.5 meters. In 2010, its branches started to fall off; then its multiple stems began to split and topple over; and by 2011 it was dead.

A similar fate befell the Platland tree in South Africa, which the authors call “probably the most promoted and visited African baobab,” perhaps because its owners built a cocktail bar inside it. Known also as the Sunland baobab, it was the biggest known individual, with a 34.11-meter-wide trunk and a height of 18.9 meters. It had lived for an estimated 1,110 years until its largest stem unit split four times in 2016 and 2017 and all five stems fell and died.

“The deaths of the majority of the oldest and largest African baobabs over the past 12 years is an event of an unprecedented magnitude,” the scientists wrote. “These deaths were not caused by an epidemic, and there has also been a rapid increase in the apparently natural deaths of many other mature baobabs.”

But the findings came under fire from other researchers who study baobabs. David Baum, a botanist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, disagreed with Patrut’s interpretation of how baobabs grow, pointing out that it was essentially based on his experience with few examples.

The baobab’s apparently unusual growth pattern, Baum added, could in fact be explained by its remarkable ability to grow more wood-generating tissue, such as when it has been wounded by a hungry elephant looking for food.

“I think he’s incorrect in his assessment of how baobab trees grow,” Baum said, referring to Patrut’s argument that baobabs grow into a ring-shaped structure. “I think he’s been misled by the way baobabs generate their bark and their wood into thinking that’s how they grow.”

And if Patrut is indeed misinterpreting the growth pattern of these plants, Baum said, this means the ages of the trees that Patrut extrapolated from his radiocarbon dating results could be very off. Trees could potentially be many hundreds of years older than the study’s estimates, he added.

On top of that, Baum said, the study does not present an actual rate of death for baobab trees, so it can’t actually quantify whether the rate of death for large baobab trees has actually increased in the past decade or so.

For his part, Baum said he suspected that the mortality rate was going up, pointing to his personal experience studying baobab trees in Madagascar.

“It’s just tragic to imagine that these gorgeous trees that have been around for millennia should die,” Baum said.

One way scientists could get a handle on the rate would be to use historical records that go to the Victorian era to quantify the death rates for documented baobabs over time, he pointed out.

As for accurate ages, he said, perhaps the best method would be to take a core sample all the way through a large tree, not just through a few tens of centimeters. But Baum said there’s a small risk of introducing fungal infections by doing so, and it would probably be a hard sell for government agencies and private owners who had large baobabs on their land.

The scientists did not study what was causing the deaths of these arboreal behemoths, though they pointed to a possible suspect: climate change in the region.

“There has been a rapid increase in baobab deaths all across their range in southern Africa over a very short time span,” Patrut wrote in an email.

Southern Africa, he added, is one of the fastest warming areas due to climate change.

“Paleoclimate evidence suggests that baobabs are adapted to wetter, drier and colder conditions, but possibly not to hotter conditions,” he wrote. “We suspect that an unprecedented combination of temperature increase and extreme drought stress were responsible for these demises.”

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Suicides have increased by more than 30% since 1999 in half the states, CDC says

Hurricanes and typhoons are slowing down, which means more time to do damage

UPDATES:

3:15 p.m. June 12: This story has been updated with additional comment from Adrian Patrut and David Baum.

9:50 a.m. June 12: This story has been updated with comments from Adrian Patrut and David Baum.

This story was originally published June 10 at 2:05 p.m.