Coronavirus Today: The people who face the greatest COVID risk

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Dec. 13. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

For most Americans, the pandemic seems to be getting better (assuming they acknowledge it still exists at all). Sure, COVID-19 cases are rising across the country, but the idea of catching the coronavirus is no longer as daunting as it used to be. Aside from seeing someone with a face mask once in awhile, it might not even occur to you that we’re in the midst of a public health emergency.

Unless you’re immunocompromised, like Louise Lerminiaux.

The Thousand Oaks resident received a kidney transplant 14 years ago, and she’s been taking drugs to suppress her immune system ever since. Those drugs prevent her body from rejecting the donated kidney. They also make her more likely to get COVID-19 and to become severely ill if she does.

Now that communitywide pandemic precautions are a thing of the past, Lerminiaux has to work extra-hard to keep herself safe. Not only does she wear a mask everywhere she goes, she hits the grocery store at 7 a.m., when the aisles are empty, and breaks out the PPE when she travels by plane.

“There is eye-rolling, for sure,” she told my colleague Melissa Healy. But she knows what it’s like to be near death, she said, and “my life is more important.”

Cindi Hilfman, a kidney transplant recipient from Topanga, can relate. She recalls being sneered at for donning a mask when she went to Iowa this summer. Reactions like that are no fun, but they won’t persuade her to drop her guard.

“I do see myself wearing my mask for years,” Hilfman told Healy. “I’m not giving up that mask.”

Nor should she. A study published last month in the journal Transplantation found that people who received transplanted organs were four to seven times more likely to die of COVID-19 than U.S. adults as a whole. As luck would have it, kidney recipients were at the high end of this range.

More than 7 million U.S. adults who take immune-suppressing drugs are in a similar predicament. Not all of them are transplant recipients. Some use the drugs to treat autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis or to prevent inflammation from reaching dangerous levels. Some are preparing their bodies for cancer treatment.

More than half a million more have cancers of the blood or lymph system, responsible for maintaining a robust immune system. When those systems are under attack, they can’t do their job. Another 400,000 or so have advanced or untreated HIV, depleting them of T cells that would help fight infections.

These 8 million or so immunocompromised Americans don’t get as much protection from COVID-19 vaccines as the rest of us because their weakened immune systems don’t produce as many antibodies. Nor do they have as many B cells, which minimize the impact of an infection.

A study of patients from10 states published this summer by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that people with compromised immune systems accounted for 12.7% of adult COVID-19 hospitalizations, even though they made up an estimated 2.7% of the adult population. Even after getting COVID-19 vaccines, those patients were 40% more likely to be admitted to the ICU and 87% more likely to die than patients with healthy immune systems.

They can’t rely on Paxlovid if they get sick because the antiviral isn’t safe with other medications they typically take. As if that weren’t bad enough, the ever-evolving Omicron variant is sapping the potency of drugs immunocompromised people rely upon.

Evusheld, for instance, is a preventive injection that helps make up for patients’ antibody shortfall. It was heralded as a lifesaving drug after it came out a year ago. But now its effectiveness is only 25% “and dropping,” according to Harvard infectious disease specialist Dr. Jacob Lemieux.

The story is similar for bebtelovimab, a monoclonal antibody treatment to help people with mild to moderate cases of COVID-19 avoid becoming severely ill. Newer iterations of the coronavirus have evolved some resistance to the drug, reducing its effectiveness to 35% or less and falling fast, Lemieux said.

“It’s going to be tough times ahead” for immunocompromised people, said Dr. Camille Kotton, who specializes in treating people with immune impairment at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

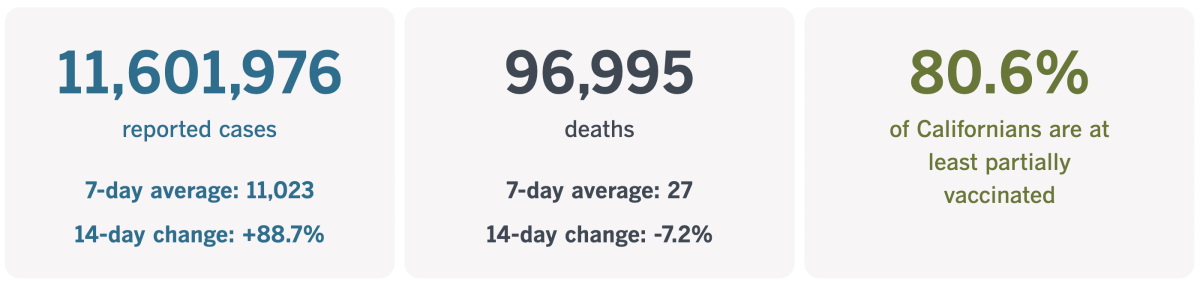

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:45 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The spreading consequences of opposition to COVID-19 vaccines

Tomorrow marks the two-year anniversary of Sandra Lindsay’s historic shot in the arm. It was on Dec. 14, 2020, that the critical care nurse in New York became the first American to receive a dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

“I feel like healing is coming,” she said at the time. And she was right. Researchers estimate that the shots saved 1.9 million lives in the U.S. during the first year alone.

Alas, this isn’t a story with a simple happy ending. More than 784,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 since Lindsay’s first dose. Some of those deaths were surely unavoidable, but hundreds of thousands could have been avoided if the country’s COVID-19 vaccination rate hadn’t stalled out below 70% and if more than one-third of Americans had opted to receive a crucial booster shot.

“The number of Americans who lost their lives because they refused the COVID vaccine is just staggering,” Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, told my colleague Michael Hiltzik. “It’s the greatest self-immolation in American history.”

If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, none of this will come as a surprise. But this might: The anti-vaccine sentiment stirred up during the pandemic is threatening childhood immunizations that have nothing to do with COVID-19.

“Anti-vaccine activism is giving parents second thoughts about giving their kids all vaccines,” Hotez said. He’s not the only one who’s noticed this.

“COVID served as an accelerant for anti-vaccine activists,” Rekha Lakshmanan, strategy director for the Houston-based Immunization Partnership, told Hiltzik.

Her evidence comes from around the country, where legislators tried to water down public health laws related to vaccines.

This year alone, 26 states enacted 51 bills about vaccination mandates, according to the National Council of State Legislatures. Some of those bills were aimed at strengthening requirements in schools and workplaces, but many were passed to make it easier for people to avoid mandates by claiming a religious or other nonmedical exemption — or to do away with the mandates altogether.

Lakshmanan said efforts to weaken COVID-19 vaccine rules were particularly notable in red states, including Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Tennessee and Utah. On their face, the bills appear to focus on COVID-19 shots; in truth, their purpose is broader, she warned.

“Those kinds of bills served as a Trojan horse for what the opposition is really trying to do, which is undermine the public health infrastructure and push vaccines and vaccination into the shadows,” she said. “The ultimate goal is to go after all childhood wellness vaccines.”

Indeed, childhood vaccinations have taken a hit since the arrival of the coronavirus. In part, that reflects the fact that all kinds of routines were disrupted by pandemic lockdowns, and some still haven’t returned to normal.

But that’s not the whole story. Refusing to follow the advice of medical experts regarding vaccination has become a way to show allegiance to a particular brand of Republican partisanship.

(It should be noted, however, that former President Trump was instrumental in the speedy development of the COVID-19 vaccines and even urged his supporters to take them, like he did.)

In a way, the vaccines themselves are to blame. They’ve done such a good job of eradicating scourges like polio and measles that some parents fail to appreciate how dangerous those diseases can be.

They may get a reminder soon. A growing measles outbreak in and around Columbus, Ohio, has spread to 74 children as of Tuesday, according to local health officials. None of the infected children have died, but 26 were admitted to a hospital.

Health officials say 69 of the 74 patients had never received the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, and four others were partially vaccinated. (The vaccination status of the remaining patient was unknown.) Eighteen of the patients were less than a year old — too young to get the first of two recommended doses of the MMR vaccine.

Nationwide, the CDC counted 88 measles cases this year as of Thursday, up from 49 in all of 2021 and 13 in 2020. This despite the fact that MMR shots are 93% effective at preventing the disease that kills more than 140,000 people around the world each year. Most of the victims are under 5 years old.

It’s not hard to imagine the situation getting worse. In 2019, the U.S. recorded a whopping 1,274 measles cases in 31 states.

“What we really need is help from the National Academy of Sciences, scientific and professional societies, university presidents,” Hotez told Hiltzik. “We need voices to say, ‘Enough: We’re a nation built on science and technology, and we’re not going to stand for this anymore.’ ”

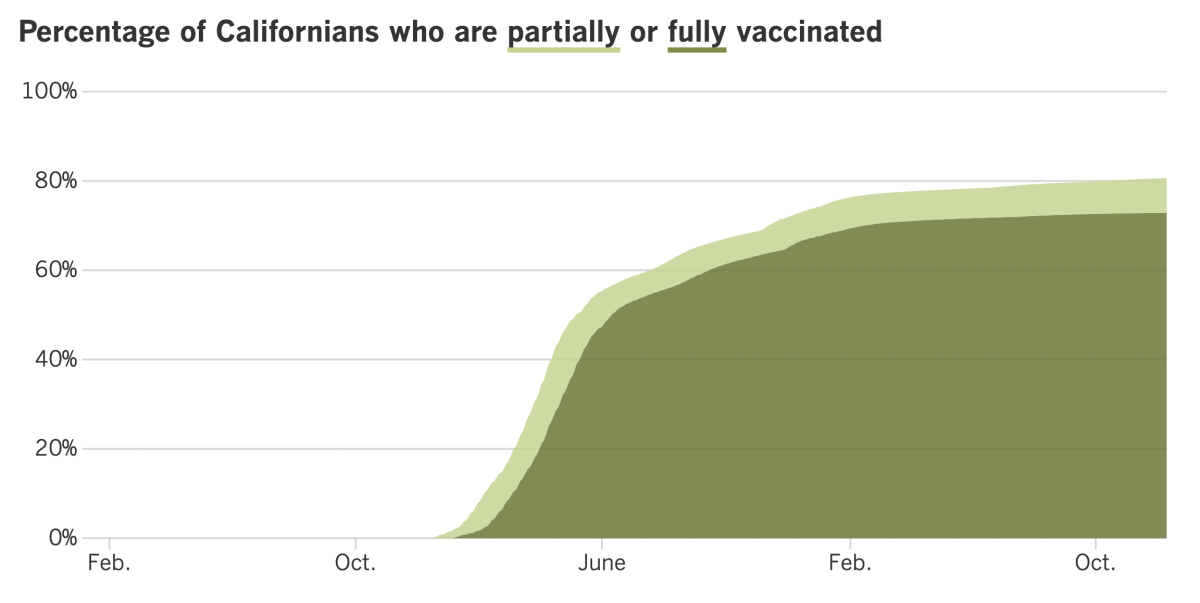

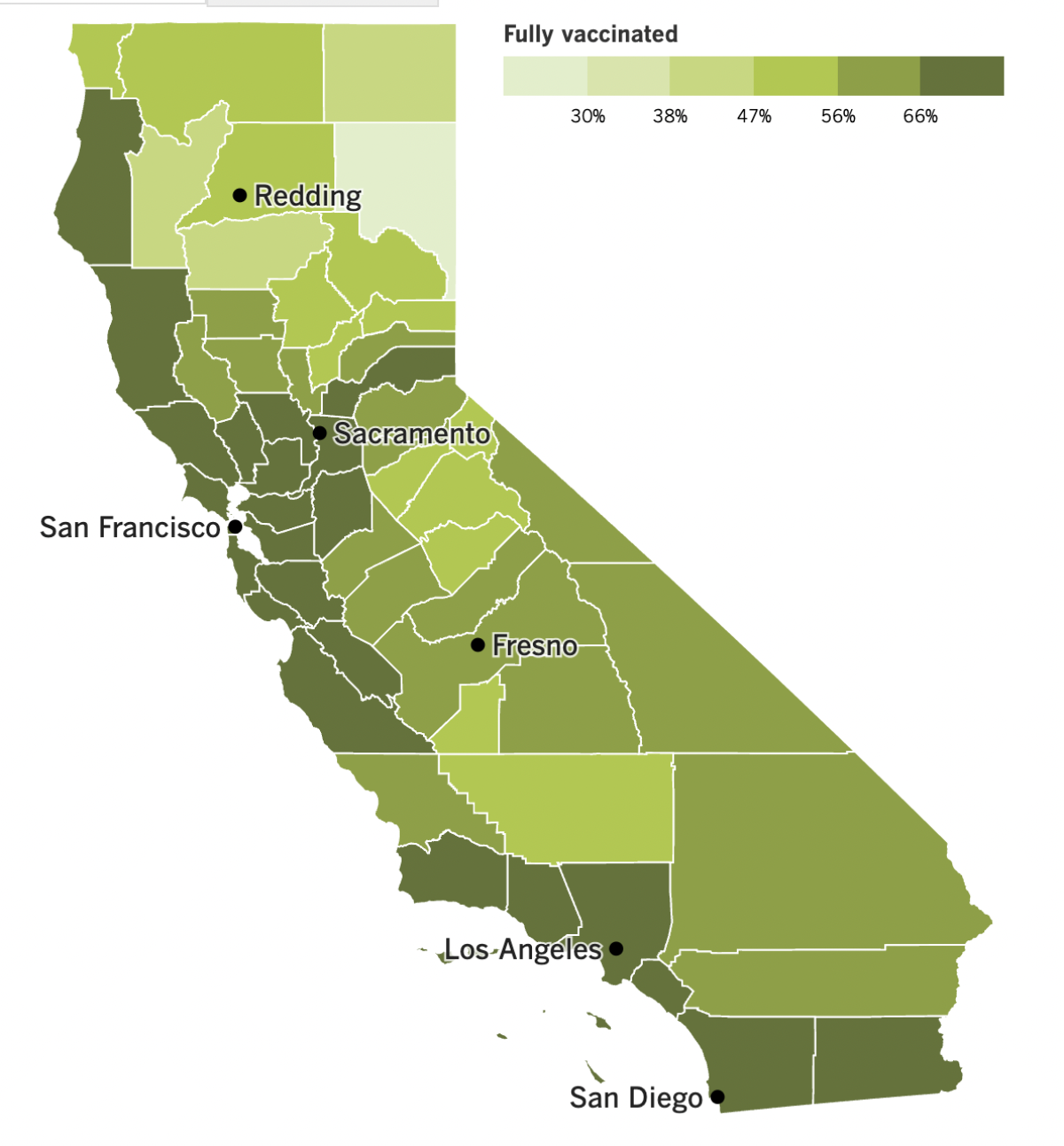

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Let’s start with some hopeful news for a change. It comes from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, where researchers have developed an experimental COVID-19 drug that’s designed to remain effective no matter how much the coronavirus mutates.

To understand how it works, you have to know that when the virus enters a human body, it looks for a certain type of receptor on the surface of cells in order to bind with them. Once joined with that receptor — known as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2 — the virus jabs in its spike protein and initiates an infection.

The new drug, dubbed DF-COV-01, is meant to impersonate the ACE2 receptor so it can lure the virus away from real ACE2 receptors on cells. When it succeeds, the drug permanently disables the virus’s spike protein and renders it harmless. It was described last week in the journal Science Advances.

The shape-shifting coronavirus has a track record of mutating in ways that reduced the effectiveness of vaccines and antibody treatments. But here’s the clever thing about the new decoy: If the virus were to evolve in a way that made it resistant to the drug, it would also become less adept at binding to cells. If it can’t bind, it can’t spread itself inside the body.

The drug has been tested only on animals, and the results in hamsters were promising. Independent researchers said the work was “elegant,” but there was a long way to go to turn DF-COV-01 into a real treatment. “The devil is in the details,” one said.

And now for the bad news. Just last week we were lamenting the fact that Los Angeles County’s “low” COVID-19 community level had been downgraded to “medium.” It was nice while it lasted — as of Thursday, the level in California’s most populous county is considered “high” by the CDC.

L.A. County has company — San Bernardino, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Benito, Imperial, Kings and Tuolumne counties are also in the “high” zone. Orange County still has a “medium” COVID-19 community level, along with San Diego, Riverside and Ventura counties, among many others.

Despite this worsening trajectory, L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said last week that when she looked at all the relevant metrics, she found reason to believe we can turn things around in time to avoid a new indoor mask mandate. “I’m feeling more hopeful that our metrics might improve before they tank,” she said.

Her optimism wasn’t off-base. The county’s case rate over the past week is 18% lower than it was a week earlier. Even better: New hospitalizations of people with coronavirus infections are down 9% week-to-week.

If you want to things to keep moving in the right direction, Ferrer’s advice is simple: Choose to wear a mask indoors even though you don’t have to (yet).

“We all need to wear our mask now,” she said. “There’s just too much transmission, and it’s creating a lot of risk. And the time to mitigate the risk is actually now.”

Remember, it’s not just COVID-19 that is straining the healthcare system right now. The “tripledemic” of COVID-19, flu and RSV is in full swing.

To accommodate the demand, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Westwood is doubling up patients in rooms designed for one. Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center turned its auditorium into a flu clinic. Children’s Health of Orange County has converted playrooms into patient rooms and set up beds in corridors.

At Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, some ER patients have been forced to stick around for hours while doctors wait to discharge patients to skilled nursing facilities.

“We can’t discharge them until we have a place to put them,” said Dr. Kimberly Shriner, medical director of infection prevention at Huntington Health. “And so you can see what happens — it just backs up. And then we don’t have enough beds. And then people sit in the ER for 10 hours.”

You don’t need to go to a hospital to appreciate how much viral activity there is now. Just go to a drug store and try to buy cough syrup or fever-reducing medication.

Johnson & Johnson said its factories are running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to produce Tylenol. Other companies are making cold and flu aids as fast as they can, the Consumer Healthcare Products Assn. assures us. In other words, the trade association says, the problem isn’t too little supply, it’s too much demand.

Shoppers have been snapping up whatever medicines they can find to ensure that they won’t be empty-handed later, exacerbating the problem for others. Antonieta Garcia of East Los Angeles has been buying what she can for the sake of her two kids. (One has asthma; the other is immunocompromised.) “I decided I had to stock up,” she said.

It kind of reminds you of the run on toilet paper in the pandemic’s early days.

The trade association emphasized “the importance of responsible purchasing practices.” Otherwise, fears about shortages will become into a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Let’s turn to a product that has the opposite problem: COVID-19 vaccines. Versions that target the Omicron variant are now available to children as young as 6 months. The Food and Drug Administration authorized tiny bivalent doses from Moderna and Pfizer on Thursday, and the CDC endorsed them on Friday.

The rules for this youngest age group are a little complicated. Children under 6 who’ve had their two primary doses of Moderna’s vaccine can get the company’s bivalent booster if at least two months have passed since their last shot.

But children under 5 who’ve had their three primary doses of the Pfizer vaccine will have to wait at least a month to learn when they can get one of the new boosters. Children who have started — but not yet completed — their three-shot series will get the bivalent formula for their third dose.

It remains to be seen whether the ability to target Omicron will entice more parents to vaccinate their young children. As of last week, only 3% of kids under 2 and about 5% of those 2 to 4 were fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

And finally, we have a big update from China. After months of domestic complaints about the country’s “zero COVID” policy, and two weeks after the deadly apartment fire in Urumqi that sparked the biggest protest in a generation, the government responded by easing some rules around coronavirus testing requirements and isolation procedures for people with active infections.

The rollback was greeted with both relief and apprehension. Almost immediately, people were able to do mundane things like going to the gym without having their smartphones scanned or their whereabouts tracked. Children in areas without outbreaks were able to go back to school.

Some people took advantage of their newfound freedoms to buy medicines they’ll need if fears of a widespread outbreak come to pass. Some pharmacies in Beijing ran out out of cold and fever drugs.

“Every country in experiencing their first wave will face chaos, especially in medical capacity, and a squeeze on medical resources,” said Wang Pi-sheng, who leads Taiwan’s COVID-19 response.

Within days, reports of outbreaks in schools and businesses were cropping up on social media. But they weren’t reflected in the official statistics now that fewer people are required to get to mandatory testing.

“Half of the company’s people are out sick, but they still won’t let us all stay home,” an unnamed person from Beijing said in a post on a Chinese microblogging site.

In Beijing, the number of people visiting hospital fever clinics grew by a factor of 16 in a single week. A waitress in the capital said customer traffic at her restaurant was down because so many were ill. “The first one or two months are definitely going to be serious,” she said. “Nobody’s used to this yet.”

Undaunted, Chinese officials proceeded with more rollbacks on Monday. They disabled the app that tracked people’s travel between cities, instantly reducing the number of people who could be told to quarantine if a new COVID-9 hot spot emerges.

Officially, China is still committed to zero COVID. But the changes suggest a willingness to accept more illnesses in order to get the country moving again. In an ominous sign, the government is opening additional intensive care facilities to tend to severely ill patients.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What would it take for L.A. County to bring back its mask mandate?

The criteria are the same as they were this summer, when officials were on the verge of amending the county health order to require that masks be worn in indoor public spaces. They include:

A lot of infections. Specifically, the county would have to see at least 200 new cases per 100,000 residents per week. (There’s a way to trigger a mask mandate with a lower case rate, but that would require a combination of factors that’s extremely unlikely to occur.) As of Tuesday, the case rate in L.A. County is close to 272 per 100,000 per week.

A lot of infected people being admitted to hospitals. “A lot” means at least 10 new patients per 100,000 residents per week. It’s important to note that the coronavirus doesn’t have to be the thing that sent them to the hospital in order to count toward the total. Even if a patient is admitted because they’re having a baby or got into a car accident, they’ll use up more healthcare resources if they’re infected. As of Tuesday, the new admissions rate for L.A. County is just under 15 per 100,000 per week.

Infected people taking up a significant share of hospital beds. This is a way of measuring the county’s capacity to care for people with serious cases of COVID-19 as well as everyone else who might need an inpatient bed. The threshold for entering mask-mandate territory is having at least 10% of beds being taken up by coronavirus-positive patients. (That 10% figure is measured as a seven-day average.) As of Tuesday, infected patients filled 6.9% of hospital beds in L.A. County.

If the county were to meet all three criteria, the countdown toward a mask mandate would begin. If we remain in the danger zone for the following two weeks, the mandate would go into effect.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The photo above shows members of the Dallas Cowboys taking the field in a game against the Philadelphia Eagles. The fact that the hometown stands are mostly empty should clue you in to the fact that this game was played in 2020, during the NFL’s first pandemic season.

That’s relevant because of a new study that examined the public health implications of that season’s 269 games. Unlike other professional sports leagues that instituted temporary bans on fans in the stands, the NFL allowed home teams to decide for themselves whether to allow spectators to cheer in person. About 43% of the games were played before crowds, which ranged in size from 748 to 31,700. Some of the largest were at the Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium.

Researchers found that bigger crowds were associated with bigger increases in COVID-19 caseloads. In the two to three weeks after a game, those increases were more than twice as high in counties where more than 20,000 fans attended than in counties where attendance was below 5,000.

“Given what we knew about COVID-19 and the way it spreads, we weren’t terribly surprised by our findings,” study co-author Wanda Leal told my colleague David Wharton.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.