Coronavirus Today: Breakthrough infections break through

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, July 23. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer dropped a big number on us yesterday: Of all the confirmed coronavirus infections reported to the county last month, 20% were in people who had been fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Let’s pause for a moment to let that sink in. In June, one out of every five coronavirus infections here occurred in someone who was fully vaccinated.

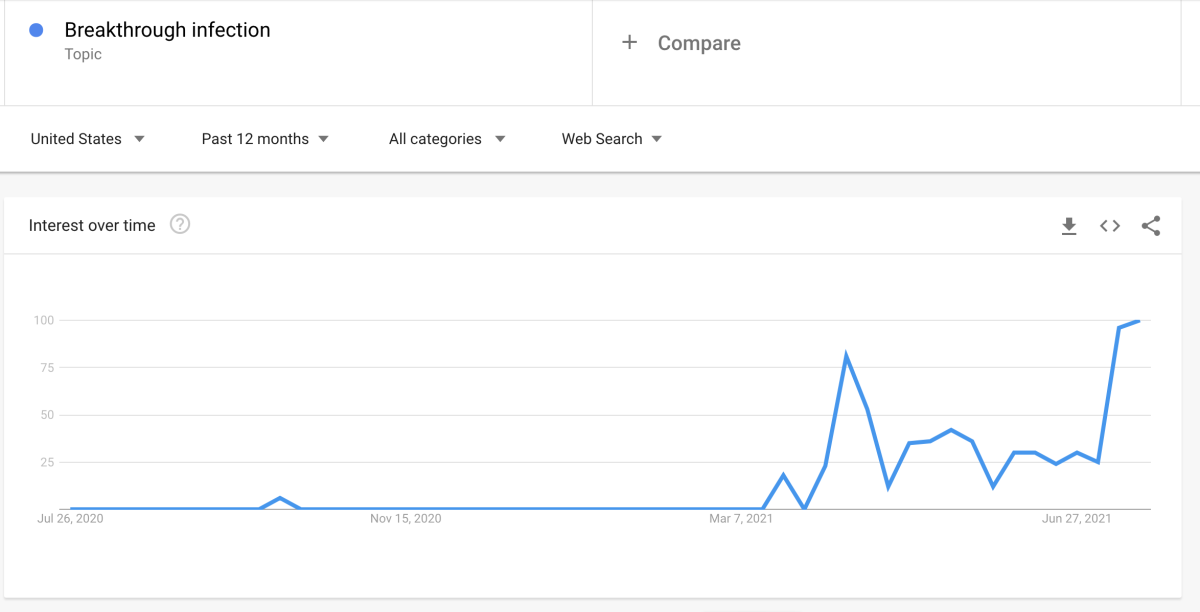

These so-called breakthrough infections are on the rise in places throughout the country. Google Trends indicates that search interest in the topic has never been higher ...

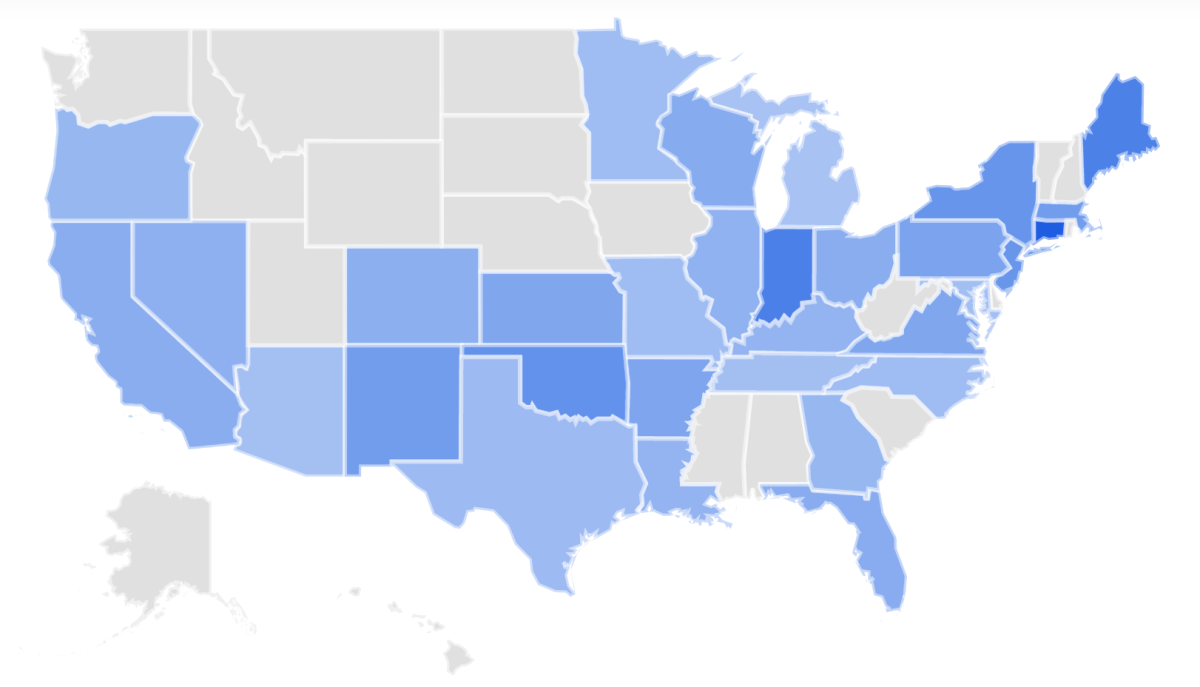

... and is hardly limited to California or the west.

The 20% figure may sound unsettling, especially considering that just last week L.A. County health officials were touting the fact that more than 99% of all COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths were among the unvaccinated. Have vaccines suddenly lost their power to protect us from the coronavirus?

Hardly. If that were the case, we’d be seeing a whole lot more sick people among us.

In L.A. County, the odds of becoming infected are 5.1 times higher for people who are only partially vaccinated or completely unvaccinated than they are for people who are fully vaccinated. But about half of county residents — 53% to be exact — are fully vaccinated. If none of them were vaccinated, the total number of infections would be 67% higher than it actually is.

Here’s how that works:

Let’s say that among partially vaccinated and unvaccinated people, there are 10 new infections per 100,000 people per day. If that’s 5.1 times higher than the rate for fully vaccinated people, there would be 2 new infections per 100,000 people per day in that group.

L.A. County is home to 10 million people. Among the 5 million who are unvaccinated or partially vaccinated, there would be 500 new infections per day, plus another 100 among the 5 million people who are fully vaccinated. That’s a total of 600 new infections per day. But if no one were fully vaccinated, we’d be looking at 1,000 new infections per day countywide — a figure that’s 67% higher.

You can flip this around and say that compared to a scenario where no one was fully vaccinated, having half of the county fully vaccinated reduces the number of infected people by 40%.

The more people we vaccinate, the more infections will decline. If 75% of county residents were fully vaccinated, the total number of infections would fall by 60%. And that doesn’t account for the fact that we’d be pretty close to herd immunity, which would reduce infections even more.

So despite the increase in breakthrough infections, COVID-19 vaccines are doing their job. Plus, on an individual level, they dramatically reduce the likelihood of severe illness or death if someone does become infected. More than 97% of Americans now hospitalized for COVID-19 are unvaccinated, according to Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It’s worth remembering that no vaccine is 100% effective. When the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines were tested in clinical trials before the more transmissible Alpha and Delta variants were on the scene, they had efficacies of 95% and 94%, respectively. Even then, a small percentage of fully vaccinated people were still susceptible to infections.

Ferrer likened the vaccines to seat belts.

“It wouldn’t really make sense to not use a seat belt just because it doesn’t prevent all injuries from car accidents,” she said. By the same token, “rejecting a COVID vaccine because they don’t offer 100% protection really ignores the powerful benefits.”

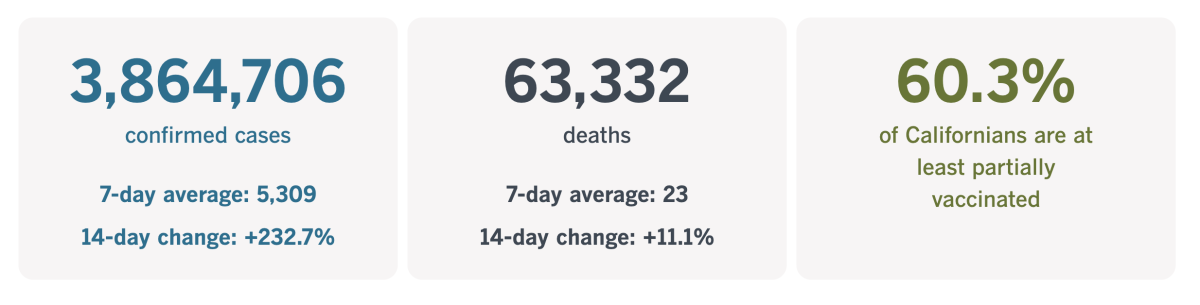

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 3:34 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How to improve quarantine

The pandemic tested Americans’ ability to pull together for the sake of the common good. We earned high marks in some areas — most notably, developing multiple COVID-19 vaccines in a matter of months — but other aspects of our coronavirus response left room for improvement. That includes our willingness and ability to quarantine.

Technically, the term quarantine refers to a period during which a person who has been exposed to an infectious disease is kept away from others until they know they’re in the clear. During the Ebola outbreak of 2014, health workers who treated patients in Africa were asked to keep to themselves for 21 days when they returned to the U.S., until the virus’ incubation period had elapsed.

In 2019, the U.S. government established a National Quarantine Unit at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. It was pressed into service the following year, becoming the temporary home of more than a dozen people who had been exposed to the then-novel coronavirus aboard the ill-fated Diamond Princess cruise ship.

For all its state-of-the-art amenities, the quarantine center has a serious problem: It has room for only 20 people. As we’ve learned the hard way, that’s woefully inadequate for a modern pandemic.

Instead, what passed for a quarantine in the COVID-19 era was the patchwork of “shelter in place” mandates and stay-at-home orders issued by state and local health authorities. But according to a new book on the history of quarantines, what we really needed was a more stringent, broad-based lockdown.

“We just didn’t have the grit for it in the United States,” one expert is quoted as saying. “It’s quite humbling.”

The book is called “Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine,” and it was written by journalists Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley. They began mulling the topic in 2009 when they happened upon an old quarantine station in Australia that had been converted into a hotel and spa. As it happens, they wound up writing most of the book while staying at home themselves last year.

With the economy reopened and society returning to normal — in the United States, at least — you might think Manaugh and Twilley missed the boat. They disagree. Given the way humans are encroaching ever further into wild areas, we’re bound to encounter all sorts of novel pathogens for which our bodies have no natural defense. If a virus can take root anywhere, it will have the potential to spread everywhere. Quarantine will have to be part of the public health response.

“The hope would be that COVID-19 lets us take a moment and think about quarantine and do it better the next time,” Manaugh said.

Not all of the shortcomings in the U.S. were due to poor planning. Manaugh pointed out that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed a detailed strategy for quarantine, testing, contact tracing and isolation — and other countries did an admirable job of implementing parts of that plan. What was missing was a recognition that political partisanship had the potential to undermine everything.

“There isn’t a strong civic culture anymore, and you can’t have public health without a public,” Twilley said. “People conflated liberty with the freedom to move around as they wished. We need to have a more sensible conversation about what we mean by freedom, but that’s a huge topic.”

She added that the more unequal a society, the more difficult it is to implement a quarantine in a way that’s fair to everyone.

Inequality is baked into our country, but that doesn’t mean we’re doomed to repeat our mistakes. We can invest in quarantine preparedness like we do for earthquakes, hurricanes and other natural disasters, Manaugh said. Being up front about it will make it seem like a normal part of life instead of a suspicious government plot.

Twilley offered another way to get the public on board with a quarantine: Present it as a choice instead of a mandate.

“Quarantine will always be a little leaky and never will be perfect,” she said. “But it doesn’t have to be perfect to work in terms of flattening the curve. It does have to get better. The point of our book is that people know how to make it better.”

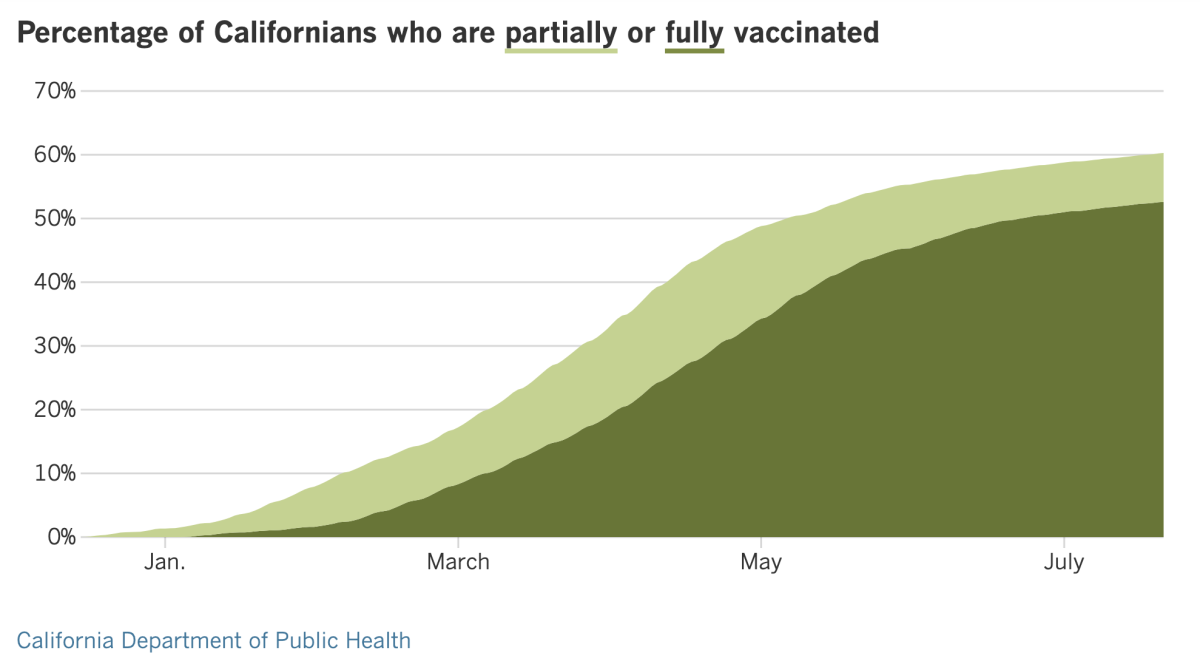

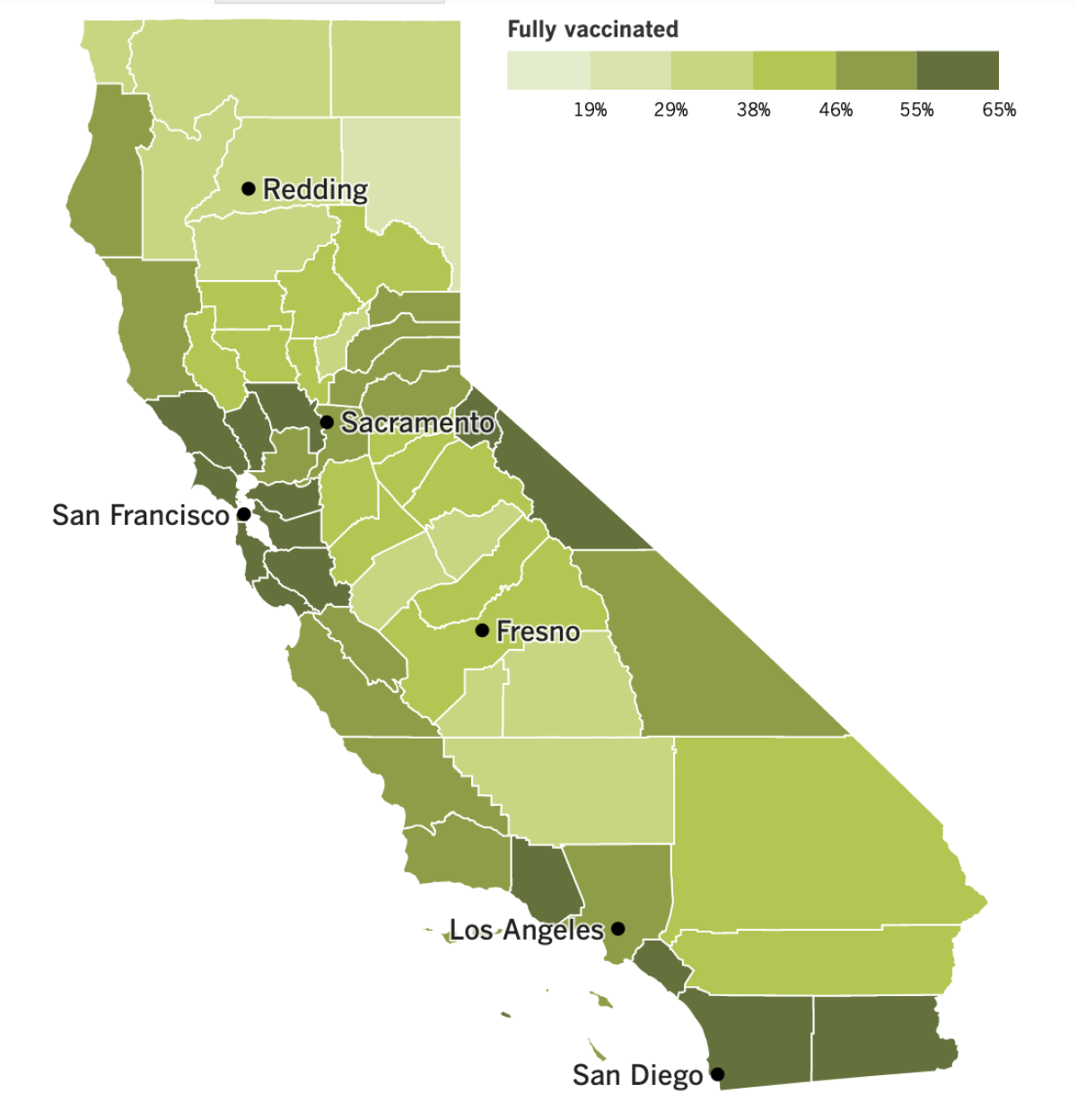

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

Coronavirus cases in L.A. County are reaching levels not seen since the waning days of the winter surge. Health officials reported 2,767 new cases on Thursday, the second day in a row that newly confirmed infections topped 2,000.

The number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is rising too, reaching 688 as of Friday. That number is roughly triple what it was a month ago.

Luckily, death tolls remain relatively low, averaging about four a day in L.A. County and about 22 across the state, according to data compiled by The Times.

Numbers like these are prompting more counties to get tough. Starting Monday, everyone entering a San Mateo County facility will be required to wear a face mask whether they’ve been vaccinated or not. And Santa Clara County plans to require COVID-19 vaccines for all county employees.

Santa Clara County officials joined with their counterparts from San Francisco and Contra Costa to ask private employers in their counties to make vaccination mandatory for their employees too.

“Unvaccinated workers pose a risk not only to themselves but also to their coworkers and the members of the public they interact with,” Contra Costa County Health Officer Dr. Chris Farnitano said Thursday. “Employers have an obligation to provide safe workplaces for their employees.”

Around the country, the fast-spreading Delta variant may be scaring some vaccine-hesitant people enough to make them roll up their sleeves. White House officials said Thursday that vaccination numbers are starting to rise in some states where COVID-19 cases are soaring.

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Missouri and Nevada are among the states where vaccinations are rising in tandem with new infections. In Louisiana, where only 36% of the population is fully vaccinated, there were 5,388 new cases on Wednesday and another 2,843 on Thursday. One health system that serves residents of Louisiana and Mississippi said interest in the vaccines has increased 10% to 15% in the last week or so.

Life expectancy for Americans fell by 1.5 years in 2020, and 74% of that decline was due to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new report from the CDC.

U.S. deaths topped 3.3 million last year — a record high for the country — and about 11% of them were due to COVID-19. More than four in five COVID-19 fatalities involved people ages 65 and up. Had the disease killed more people in the prime of their lives, the impact on life expectancy would have been even greater.

As it was, the drop seen in 2020 was the largest one-year decline since World War II. The toll was even worse for Black and Latino Americans, who saw their life expectancy fall by three years.

Overseas, the Delta variant has propelled the COVID-19 death rates of Indonesia, Malaysia and Myanmar past the peak per-capita death rate seen in India. Low vaccination rates and the public’s weariness of pandemic prevention measures have also contributed to the dire situation, according to Abhishek Rimal, the Asia-Pacific emergency health coordinator for the Red Cross.

India’s seven-day rolling average of COVID-19 deaths per 1 million people peaked at 3.04 in May. On Wednesday, the equivalent figures were 4.37 for Indonesia, 4.29 for Myanmar and 4.14 for Malaysia.

And finally, the effort to figure out how this all started suffered a setback Thursday when Chinese officials rejected the second phase of the World Health Organization’s plan to study the coronavirus’ origins because it includes a deeper look into whether the virus could have leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Zeng Yixin, vice minister of China’s National Health Commission, said he was “rather taken aback” by that provision and dismissed the lab leak theory as a rumor that ran counter to common sense and science.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, said last week that the global health agency’s initial conclusion that a lab leak — either accidental or intentional — was highly unlikely had been “premature.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Who is enforcing L.A. County’s indoor mask mandate?

Just because the L.A. County Department of Public Health requires everyone to wear face coverings when they’re in indoor public places doesn’t mean people will go along with it 100% of the time. And it’s not like the health department has a police force that will round up people who fail to comply.

Technically, those who violate any part of the county’s health officer order can be punished with a citation or a fine. But those are rarely doled out, and it doesn’t look like things will be much different with the face mask mandate, my colleague Luke Money reports.

Instead of giving out punishments, health and law enforcement officials prefer to educate people who violate the rules and urge them to change their ways.

Los Angeles Police Department Chief Michael Moore said this week that his officers and staff would “wear masks in all public settings,” including indoor settings, and he asked civilians to do the same.

“The department continues to ask all Angelenos to abide by the mask mandate, recognizing that the recent resurgence is troubling,” Moore said.

L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva is on record saying his deputies will not enforce the indoor mask mandate, which he said is “not backed by science and contradicts the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines.”

That’s not exactly true. The CDC says it’s safe for people who are fully vaccinated to resume normal activities without wearing masks or practicing physical distancing. But the agency also says that fully vaccinated people should wear masks if they’re “required by federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules and regulations” — as they are in L.A. County.

And as we’ve explained before, the rationale behind the universal indoor mask mandate is that it’s necessary to get people who are not vaccinated to wear face masks indoors. Unvaccinated people are the true target, but since there’s no easy way to tell who’s vaccinated and who’s not, the rule applies to everyone.

Though individuals probably won’t find themselves in legal jeopardy for flouting the mandate, that may not be the case for business. The health department warned that “when compliance is not achieved at worksites and businesses, enforcement may include issuance of a notice of violation or a citation.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

We all knew this was coming, but it’s still jarring to see: The opening ceremony at Olympic Stadium in Tokyo with no one in the stands.

“This feels sort of like taking the tour at Dodger Stadium with the team on the road,” my colleague Dan Woike observed from inside the mostly empty stadium.

By pixelating the seats, it sort of looked like a normal crowd — at least from a distance. But the actual crowd was outside the stadium, protesting the decision to move forward with the Games in the midst of a pandemic that’s far from over.

One part of the ceremony featured the John Lennon song “Imagine,” a choice Woike found ironic. “It’s not hard to imagine how this could’ve been a much better situation,” he wrote.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.