Coronavirus Today: Just how bad was the latest COVID-19 surge?

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Thuc Nhi Nguyen, and it’s Thursday, Feb. 18. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Yesterday, we noted the good news that new coronavirus cases are down to pre-Thanksgiving levels across California. Gov. Gavin Newsom was optimistic that the economy could continue to reopen now that the worst of the surge is behind us.

But as healthcare workers exhale slightly, officials are trying to assess just how bad things got during the holiday surge that had hospitals turning their gift shops into temporary intensive care units and patients stuck in ambulances waiting hours for an open bed. My colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Soumya Karlamangla have been digging into a big question of their own: Did the unprecedented surge in COVID-19 patients increase the risk of dying in the hospital?

“Frankly, the public deserves an answer to the question,” said Dr. Roger Lewis, director of COVID-19 hospital demand modeling for the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

L.A. County has reported a total of over 19,000 COVID-19 deaths, and more than 12,000 have come since Nov. 1. But that doesn’t necessarily mean a patient who entered the hospital during the most recent surge was more likely to die than if they‘d been hospitalized with the same severity of illness earlier in the pandemic.

With too many patients for too few healthcare workers, it seems like “common sense” that outcomes would have been worse in recent months, said Cathy Chidester, director of the county’s Emergency Medical Services Agency. There are also questions about whether the stress of treating the high number of severely ill COVID-19 patients hurt other patients. For example, people who suffered heart attacks and strokes faced delays in getting treatment, and others may have put off necessary medical care for fear of contracting a coronavirus infection at the hospital.

Despite how bad things got, no hospital in L.A. County formally declared it was operating under “crisis standards of care.”

Though there were certainly examples of poor quality of care, it’s possible these problems did not become widespread. Maybe we stopped just short of overwhelming the county’s hospitals, as Lewis believes. Also, having a surge later in the year when doctors and researchers had learned more about how to treat patients with COVID-19 may have helped avoid the earlier disasters seen in places like Wuhan, China, northern Italy and New York City.

The reports of overworked doctors at a Lynwood hospital arguing about whether an elderly patient should be hooked up to one of the few remaining ventilators or of stroke patients waiting hours for time-sensitive CT scans that would influence their course of treatment were haunting. Reconciling these stories with hard data on whether patients were substantially harmed on a large scale may take months — or even a year.

By the numbers

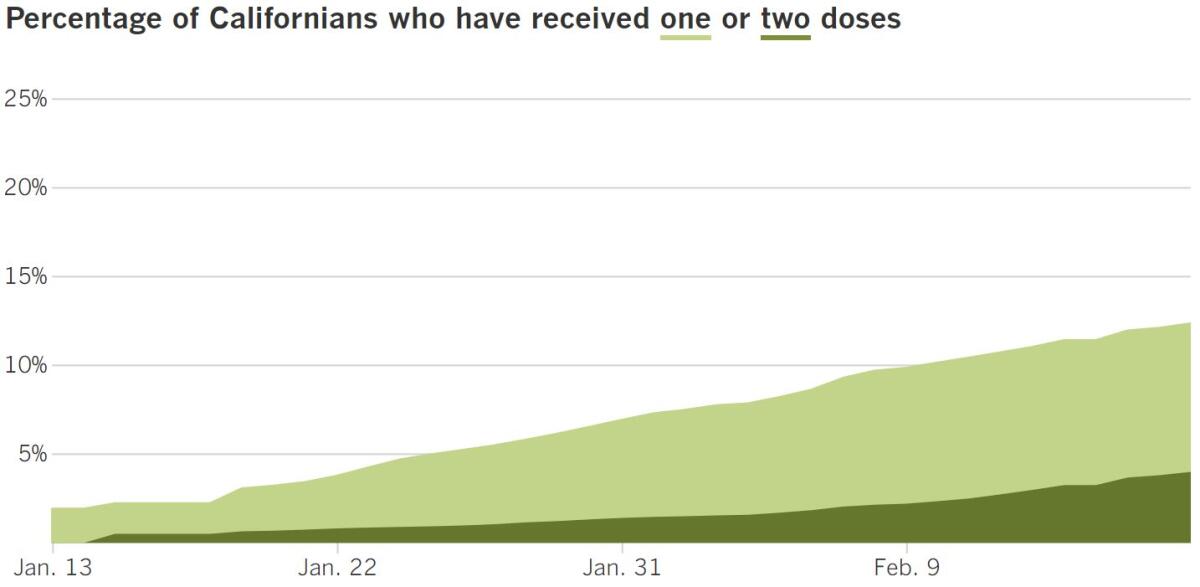

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:39 p.m. on Thursday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

A little-known category of small residential care homes is falling through the cracks of California’s vaccine effort. Unlike larger assisted-living facilities, these so-called board and care homes are usually family-owned and operated. They employ a handful of caregivers instead of nurses and don’t maintain administrative offices to handle paperwork or medical records.

Their small size and independent nature appear to have hindered their access to vaccine doses. Board and care homes can house up to six residents each, and when you add up the nearly 6,000 operating in California, it leaves almost 35,000 older people struggling to access COVID-19 vaccines despite their eligibility as a prioritized group. L.A. County alone has 1,200 board and care homes.

Many board and care home operators expected to hear from CVS or Walgreens, the pharmacies deputized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to distribute vaccines to nursing homes. Instead, they heard nothing. And when the board and care home administrators reached out themselves, they got the runaround. Some were told they must wait until March, even though their clients are in a priority group.

“We are taking care of residents in their 90s,” said Theresa Carr, an administrator at three board and care homes in Santa Clara County. “There should have been a better plan.”

The city of Long Beach is one of several jurisdictions in the state that was forced to arrange its own mobile vaccination campaign to reach people in this overlooked group. Columnist George Skelton writes that California needs to expand a similar program to reach shut-in seniors and people with disabilities.

Home delivery of COVID-19 shots is a goal tucked into the contract announced Monday between the state and Blue Shield of California. The partnership is intended to expand and coordinate vaccinations throughout the state with the help of a Blue Shield algorithm.

Blue Shield wants to administer 3 million shots a week by March 1 and 4 million a week by April 30. But how many of those doses will go to homebound seniors and people with disabilities, when it would be easier to opt for big numbers at mass vaccination sites?

The new contract says Blue Shield must arrange for the delivery of vaccines to “people who are homebound or suffering from illnesses/disabilities that make it unsafe or prohibitively difficult for them to visit a vaccine provider for a vaccination” in all 58 counties. Deciding who qualifies for the service will rest with the state, and Skelton says he’s concerned that could result in “typical, bureaucratic foot-dragging inertia.”

The Blue Shield contract is expected to help solidify the state’s vaccination system, but it won’t solve the state’s continued supply problems. The stream of COVID-19 vaccine is improving, but it’s still a trickle for people trying to get their first dose, officials say. And the winter weather wreaking havoc on much of the country isn’t helping.

In Los Angeles, thousands of vaccine appointments scheduled Friday at sites run by the city will have to be postponed after shipments of doses were delayed by storms. In Orange County, the Disneyland vaccination center closed Thursday after a shipment of the Moderna vaccine did not arrive, the county said.

And on Wednesday, the first vaccination site exclusively for Los Angeles Unified School District employees opened with only 100 doses.

Along with the short supply of shots, the first day of vaccinations at the Roybal Learning Center got off to a rocky start. Raymundo Armagnac, an educational resource aide at Denker Avenue Elementary in Gardena who turned 65 three weeks ago, was mistakenly told to arrive at 4:30 a.m. for an appointment. The start time wasn’t supposed to be until 9 a.m. And the vaccines arrived frozen and didn’t thaw until after 10 a.m.

The school district expected to receive 2,000 doses and hopes to receive the rest by the end of the week, L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner said. But even that number is way short of what’s needed to vaccinate the estimated 25,000 teachers and staff that Beutner says would allow the district to open campuses for some 250,000 elementary school students.

The outlook is better for teachers in Long Beach, which has its own health department, because all public-school employees serving kindergarten through fifth grade will have had access to first doses by week’s end, said Mayor Robert Garcia.

Equitably distributing the vaccine continues to be one of the most pressing issues of the troubled process. As of Sunday, Black residents have received just 2.9% of the doses administered statewide, according to new data from the California Department of Public Health. But as my colleague Erika D. Smith wrote, there is a Black pastor hoping to close the gap.

Noel Jones, the well-known bishop and senior pastor of City of Refuge Church in Gardena, got his COVID-19 shot and is now trying to encourage his congregants to do the same. During services streamed online, he untangles conspiracy theories and puts a trusted face to the message that vaccines are safe.

Jones received his vaccine at the Kedren Health vaccination site in South L.A., a small center that aims to get more doses to the vulnerable Black and Latino residents in the area. People who have received care there are spreading the gospel and building an almost cult-like following. “We need to come,” Jones said, “because the percentages are off.”

Finally, as Congress debates another federal coronavirus relief package, my colleague Patrick McGreevy broke down California’s own pandemic stimulus plan, which will be expedited for legislative approval next week after Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a deal Wednesday. The agreement includes:

- One-time checks for $600 to households that receive the California earned income tax credit for 2020, which is given to people making less than $30,000 a year

- A stimulus check to taxpayers with individual tax identification numbers who did not receive federal stimulus payments and whose income is below $75,000

- $2.1 billion in grants for small businesses

- $100 million in emergency financial aid for certain low-income students enrolled in community colleges

- $35 million for food banks and diapers

These benefits and more would be in addition to any federal relief programs coming out of Washington, including the $600-per-person stimulus checks already approved by Congress and the direct payments of up to $1,400 per person proposed by House Democrats.

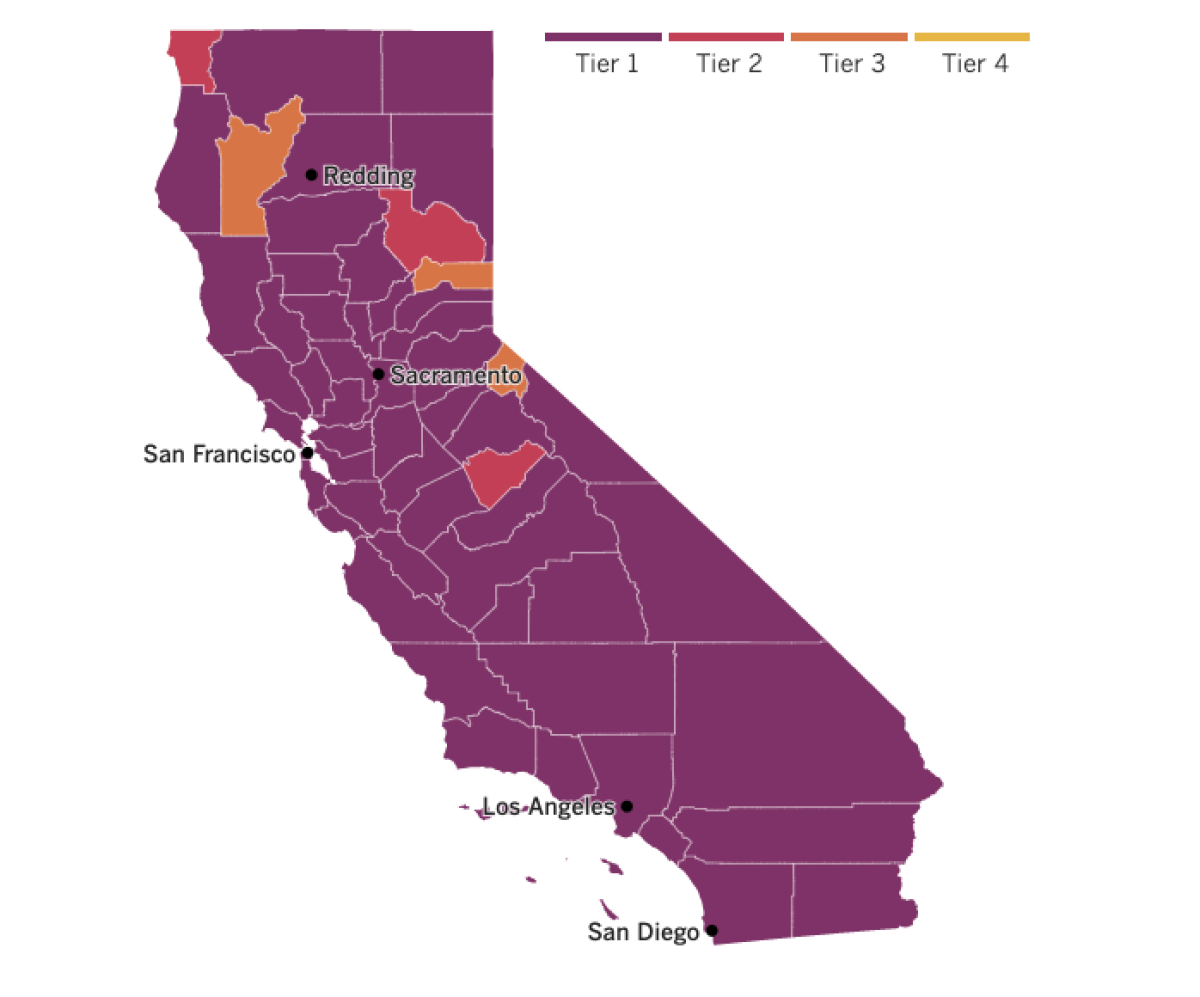

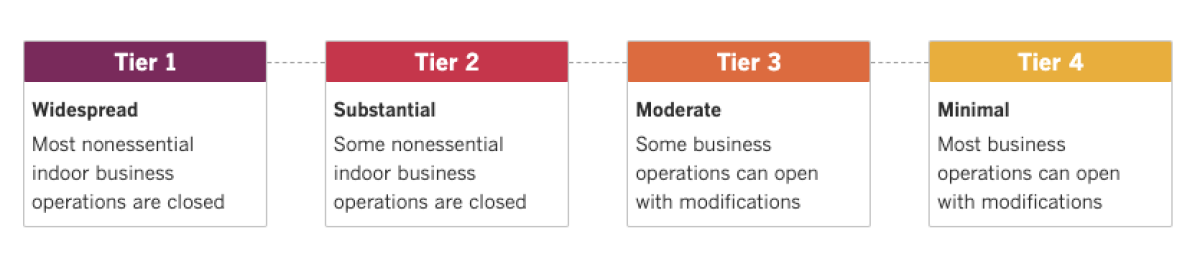

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The United States is back in the global fight against COVID-19 and is spending billions of dollars to make up for lost time.

On Friday, President Biden will announce a plan to contribute $4 billion toward combating COVID-19 around the world, reversing the course set by his predecessor Donald Trump, who withdrew from the World Health Organization.

Under the plan, half of the money, which was approved by Congress in December, will go this month to COVAX, an international partnership for acquiring and distributing vaccines to low-income countries. The remaining $2 billion will be distributed over the next two years contingent on other wealthy nations increasing their contributions. There is hope to pool at least $15 billion altogether.

“Decreasing the burden of disease decreases the risk to everyone in the world, including Americans,” a senior administration official told my colleague Chris Megerian.

The U.S. still plans to have enough vaccines to immunize every American by the end of the summer — but the possibility of new and potentially dangerous variants emerging in countries that may have to wait years to vaccinate their own populations poses a threat to the U.S. too. “This pandemic is not going to end unless we end it globally,” the official added.

Nearly 2.5 million deaths from COVID-19 have been reported worldwide, with almost 500,000 of them in the U.S. alone. American deaths from just the first half of 2020 were enough to help produce a dramatic, one-year drop in life expectancy in the United States, health officials reported Thursday.

Consistent with other aspects of the pandemic, people of color suffered the biggest impact: Black Americans lost nearly three years of life expectancy and Latinos nearly two, according to preliminary estimates from the CDC. “You have to go back to World War II, the 1940s, to find a decline like this,” said Robert Anderson, chief of mortality statistics at the agency’s National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall American life expectancy dropped from 78.8 years in 2019 to 77.8 years in the first half of 2020. The average for Black people fell by 2.7 years, to 72, and the average for Latinos fell by 1.9 years, to 79.9. White people lost an average of 0.8 years, reducing their life expectancy to 78. The preliminary report did not analyze trends for Asian Americans or Native Americans.

Abroad, my colleagues reported on Europe’s uneven vaccine rollout. Some countries such as Germany that handled the pandemic well in its early stages are dealing with frustratingly slow distribution. Residents there are especially peeved considering a German company, BioNTech, helped develop one of the first vaccines in partnership with Pfizer.

Britain, which spurned early lockdowns and paid the price with soaring case rates last spring, has now vaccinated more than 20% of its population. Despite the high vaccination rate, the country is in a third lockdown. More people are hospitalized now than last April, the peak of the first wave. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who was admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 last year, told reporters “we must be both optimistic, but also patient.”

June Ingham, a 73-year-old Londoner who received her first vaccine dose Feb. 1, was full of praise for the “amazing” vaccine rollout but said she longed for a more widespread sense of safety. “What you want is a hug,” she said. “I want one of those.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Why do I still need to wear a mask even after I’ve been vaccinated?

As my colleagues Luke Money and Rong-Gong Lin II learned, the CDC says that continued adherence to public health measures — like wearing face coverings, observing physical distancing, washing hands regularly and avoiding crowds and poorly ventilated areas — is still recommended even for those who received both required vaccine doses.

It’s a frustrating answer though, right? Why did we make such a fuss about vaccines if nothing changes after we get them?

The reason is that we know a COVID-19 vaccine can prevent individuals from getting sick, but we don’t know for sure whether the shot can prevent them from becoming infected in the first place, or from spreading the virus as an asymptomatic carrier. There are still so many people who have not yet been vaccinated and could be at risk, so wearing masks remains necessary even after you’ve been immunized.

According to Our World In Data, a project based at Oxford University, Israel is vaccinating its population faster than any other country. And preliminary research being done there suggests vaccines really do reduce the risk of transmitting the virus. Those results are “promising,” said Shira Shafir, an associate professor of epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health, but they’re not enough to allow everyone to ditch their masks yet.

Universal mask wearing, in particular, is seen as critical in keeping the spread of the coronavirus on a downward trend. A recent CDC report found that states saw meaningful declines in the growth of COVID-19-associated hospitalizations in the weeks after they imposed mask orders.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.