From the Archives: DNA testing raises a delicate question: What does it mean to be Native American?

- Share via

Reporting from TAHLEQUAH, Okla. — With the results of Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s DNA test stirring up controversy in the White House and beyond, the definition of what it means to be Native American has come into the spotlight. In this 2005 report, Times staff writer Karen Kaplan explores how the then-new commercial availability of DNA testing can challenge people’s perceptions of race and identity, particularly within native communities. This article originally ran in the The Times on Oct. 30, 2005.

Marilyn Vann can trace her Cherokee roots back more than 200 years through generations of Native Americans and the descendants of black slaves who lived among them.

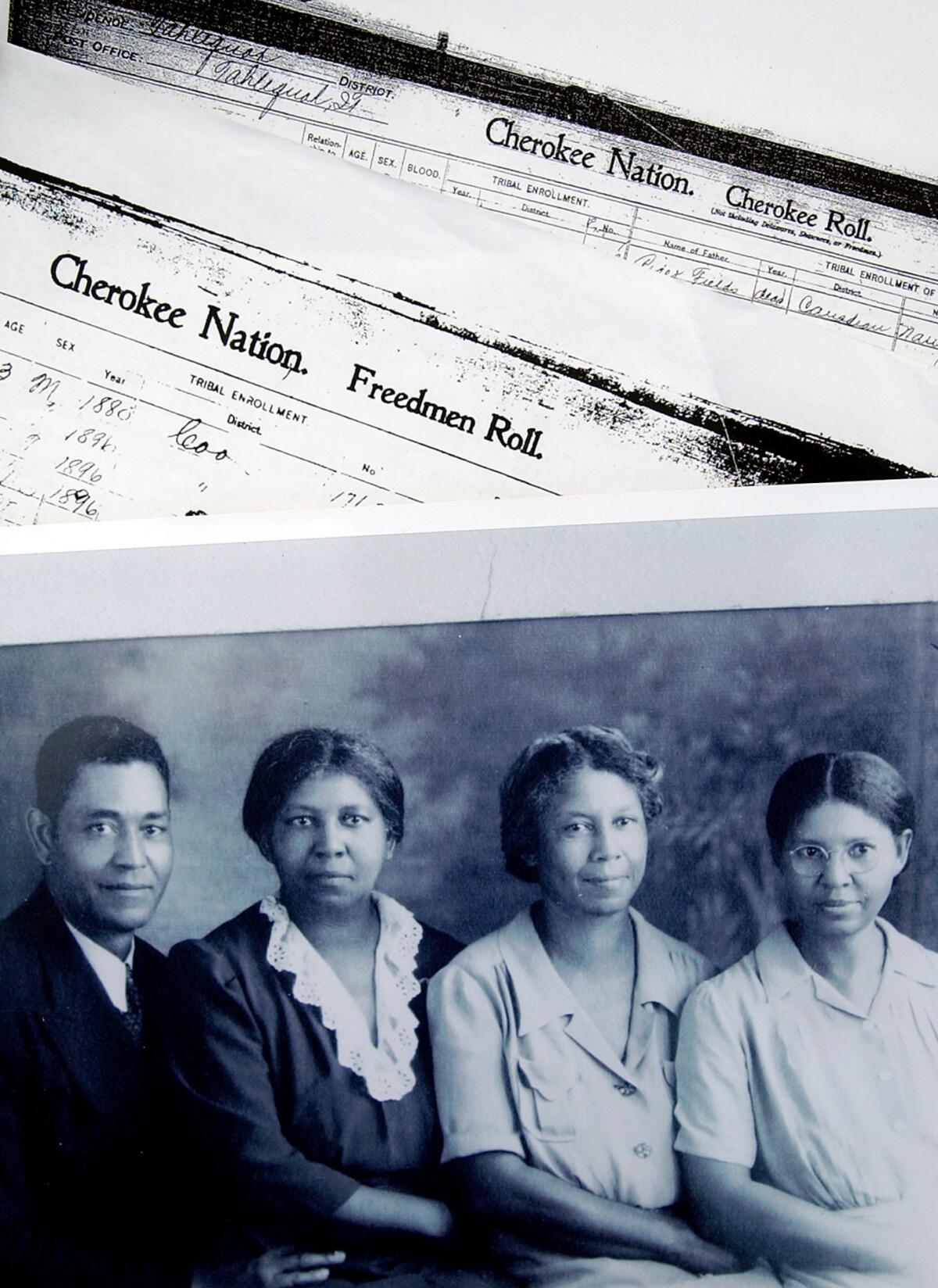

She has mountains of paper -- birth certificates, tribal enrollment cards, land deeds, affidavits, yellowing photographs -- documenting her family’s life within the tribe.

But when the engineer from Oklahoma City asked to join the 250,000-strong Cherokee Nation four years ago, she was rejected by tribal officials here who declared her black, not Indian.

The truth, she believes, is in her blood.

Vann turned to a technology that is roiling Indian tribes nationwide -- DNA testing.

From California to Connecticut, tribes and would-be members are grappling with the ramifications of a science that is able to demystify someone’s genes for as little as a few hundred dollars.

Modern genetic tests can detect traces of ancestors by looking for mutations that pass from generation to generation in specific racial groups.

More than half a dozen companies have sprung up in the last five years. Many report their most eager customers are people seeking to prove Indian heritage.

Some tribes are welcoming the new science.

The Meskwaki Nation in Tama, Iowa, began requiring DNA testing this spring to screen out pretenders seeking to cash in on the tribe’s casino profits.

“It was something we needed to be in place to protect the tribe,” said tribal council member Keith Davenport. “People are looking for an easy ride.”

But the DNA tests have opened fresh wounds throughout Indian country, unmasking complicated family relationships and turning the unspoken bonds of community into impersonal laboratory results.

Inevitably, DNA raises a delicate question: What does it mean to be Indian?

“What is up for grabs is how we define race,” said Jenny Reardon, who studies genome sciences and policy at Duke University in North Carolina. “Tribes are dealing with these issues first, but it doesn’t mean that every American might not have to deal with these issues in one way or another.”

Vann has never been uncertain about who she is.

She spent much of her childhood surrounded by Cherokees in eastern Oklahoma and enrolled in programs for Indian students at school. Her late father, George Musgrove Vann, grew up in Cherokee country attending stomp dances and speaking some Tsalagi, the official Cherokee language. He received 110 acres from the federal government in compensation for lands confiscated from the tribe when it was forcibly relocated to Oklahoma from Georgia on the Trail of Tears in the late 1830s.

It was only later in her adult life, after her daughter was nearly done with school and her career as a petroleum engineer was well established, that she contemplated a way to give back to the tribe that loomed so large when she was a girl.

In 2001, Vann applied for membership.

She got a letter back stating that her father was listed on the crucial 1907 tribal roll not as Cherokee but as Freedmen -- a descendant of the former slaves who came to Oklahoma with the tribe.

Under the rules of the Cherokee Nation, Vann could become a member only if she was directly descended from someone listed on the 1907 rolls with a fraction to denote the proportion of their blood that came from Cherokee ancestors.

According to this racial accounting, Vann’s father was 1/64 Cherokee. But the record-keeping of the time wasn’t terribly precise, and he was listed only as a Freedman.

“My ancestors helped build this tribe,” Vann said. “My father and my grandfather enjoyed Cherokee citizenship. I’ve been kicked out, with no say-so in the matter.”

The rules for tribal membership vary with each of the 562 federally recognized tribes.

In some cases, all it takes is having a parent who is a member of the tribe. Other tribes allow only mothers or fathers to pass down membership to their children. Sometimes applicants must have a full-blood Indian ancestor within four or five generations, but many don’t care if their members are blond and blue-eyed with the tiniest fraction of Indian blood.

Overall tribal enrollment has been rising steadily for at least a decade. In 1995, when the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs began keeping an official tally, tribes had 1.4 million members listed on their rolls. By 2001, the most recent year for which statistics are available, that number had topped 1.8 million.

The growth has prompted some tribes to tighten their membership rules, especially when casino money is at stake.

The Meskwaki Nation has been flooded with applications for tribal enrollment since 1994, the year the casino in Tama began sharing its profits with members, said council member Davenport. Membership swelled from 1,000 to more than 1,300.

The tribe didn’t change its enrollment criteria -- membership is still passed down from father to child. In simpler times, all it took was a signature to vouch for paternity. Now the tribe requires a 16-factor DNA paternity test, Davenport said.

At the Mashantucket Pequot tribe, which operates the lucrative Foxwoods Resort Casino near Norwich, Conn., enrollment clerk Joyce Walker regularly fields inquiries from people who say DNA tests prove they are Native Americans.

“People say, ‘I just found out I’m Indian and I want to know how I can start receiving my profits,’ ” Walker said.

She tells them to take another DNA test to prove they are the offspring of a tribal member. The news is rarely welcome.

Casino profits aren’t the only reason people want to join tribes. Card-carrying members qualify for care from the federal Indian Health Service. Some tribes offer allowances for school clothing, vocational training, aid for the elderly and other services.

Vann neither wants nor needs any of those material things.

“I have a respectable job. I have three homes, and two of them are paid off,” she said in her lakefront house in Oklahoma City. “I did not go to the Cherokees to get anything. I went to offer my services.”

Last year, an opportunity presented itself to prove what Vann thought was obvious -- that after 200 years, Cherokee and Freedmen blood had become inextricably mixed.

Rick Kittles, a genetic anthropologist, was interested in comparing the DNA of African Americans from different parts of the country. He offered to swab cells from inside the cheeks of about 150 Freedmen free of charge and tell them what proportion of their genes came from Indian ancestors.

Such tests are being offered by private companies with names like GeneTree and Family Tree DNA. Their home testing kits promise to reveal the secrets of ancestry for $200 to $400.

The genes can be examined in several ways. The most straightforward tests compare the DNA of a parent and child to confirm a biological link. When the question is racial heritage, other tests can find clues in DNA.

Of the roughly 30,000 genes spelled out in the human genome, ancestry tests focus on about 225 mutations called single nucleotide polymorphisms that arose thousands of years ago and tend to be linked to specific continents.

By examining what kind of mutations a person has, scientists can get an idea of whether one’s ancestors came from Africa, Europe, Asia or North America.

“These sequences provide a record of the history of those populations,” said Kittles, an associate professor at Ohio State University and scientific director of African Ancestry Inc., a Washington, D.C., company. “They run in families, which run in communities, which run in different geographic regions.”

But genetic and genealogical ancestry aren’t in perfect sync. Although every person has four grandparents, their DNA isn’t passed down in equal proportions. As many as 35% of one’s genes can be traced to a maternal grandfather, for example, while as few as 15% may come from the other grandfather, said Tony Frudakis, chief scientific officer of DNAPrint genomics Inc., a Florida company that offers genetic testing products.

Nor are the results foolproof. Some legitimate descendants of Native Americans may not have enough Native American genes to show up on a test, especially if their last Indian ancestor was five or more generations back. On the flip side, some people could acquire a telltale mutation through random chance.

Even those who do have Native American genes can’t tie them to the Sioux, Navajo or any specific tribe, said Ripan Malhi, a molecular anthropologist at UC Davis who specializes in Native American DNA. Tribes haven’t spent enough time in isolation to develop unique mutations.

“We’ve had a couple of tribes come to us and ask if we can come up with a genetic signature of a tribe that they could use for tribal enrollment,” said Malhi, co-founder of Trace Genetics Inc. in Richmond, Calif. “The answer is no, you can’t do that.”

Indians are quick to point out that traditional tribal records are rife with flaws. Government census takers often glanced at a person’s skin tone and guessed whether he was 25%, 50% or 100% Indian. Siblings who shared the same parents were recorded as having different degrees of Indian blood. Indians often told federal officials they were white because they feared their land would be confiscated.

Sometimes, even the unreliable documents are out of reach.

“One of the courthouses burned down, and they had all the records from the 1880s,” said Kenn Davin, a member of the United Eastern Lenape tribe in eastern Tennessee. “A lot of this stuff we can’t check out.”

The search for genetic truth, however, has some Indians worried about the consequences.

“If tribes started accepting DNA, they’d want to DNA test everybody, and everybody with a card is not going to come back positive,” said Vicky Spits Fire Garland, a Cherokee who is vice president of the Tennessee chapter of the Trail of Tears Assn. “Are they going to throw those people out?”

DNA testing could also reveal some unexpected family relationships.

“There’s a huge queasiness ... because of the social structure of Indian country,” said Laura Wass, a member of the Mountain Maidu tribe near Mt. Lassen in Northern California. “It’s going to open a lot of deep closets. A lot of children were raised by other families.... You bring in DNA and now a child finds out, ‘Well, I’m not who I thought I was.’ ”

For some, the idea of analyzing blood to distinguish some Indians from others threatens to undermine the fabric of the community.

“To define someone by blood quantum is the very definition of racism,” said David Cornsilk, a member of the Cherokee Nation.

Among the Mashantucket Pequot in Connecticut, a few tribal members have bristled at the tribe’s required genetic testing of all newborns. “They say, ‘You’ve seen me pregnant, and suddenly I have a baby in my arms. Why should I have to take this test?’ ” said Walker, the enrollment clerk. “We say we’re only trying to be consistent.”

For all the precision of the technology, sometimes it leaves more questions.

Kay Yellow Horse, who was adopted nearly 50 years ago and raised by white parents, ordered a DNA test from Seattle-based Genelex Corp. after seeing an ad at a powwow last year. The Denver writer hoped the results would tell her if there was a genetic basis for her affinity for Native Americans.

Ten weeks later, a fat enveloped arrived in the mail, confirming her Native American heritage. She burst into tears.

“My entire life I had felt like a mutt from the pound,” said Yellow Horse, who changed her last name after a divorce. “After getting those results, now I feel like a pedigreed show dog. It’s given me a feeling of authenticity.”

Though she was grateful to learn something about her roots, the results have left her wondering about her past.

“Do I have my father’s eyes?” she asked. “The hair color from my mom? Am I the product of a rape, the product of an illicit affair, or who knows what?”

Marilyn Vann’s genes told her everything she wanted to know about her ancestors.

It turns out that 3% of her genes come from Native Americans. Another 39% are from Europeans, who likely intermarried with Indians over hundreds of years; 58% of her genes originated in Africa.

The numbers roughly matched the facts in her stacks of paper. An 1835 tribal roll shows that Rider Fields, her great-great-great-grandfather, was 25% Cherokee. Other rolls from the 1800s list her great-great-grandmother and great-grandmother with Cherokee blood.

Vann has made the three-hour drive to the Cherokee Nation headquarters in Tahlequah to argue that if only her father had been properly listed on the key 1907 census, she would have her membership card and the right to vote in tribal elections.

Cherokee spokesman Mike Miller acknowledged the 1907 rolls weren’t perfect, but said it wasn’t practical for the tribe to tinker with it 100 years after the fact. As for her genetic test, Miller said it had nothing to do with the criteria for membership.

Vann has filed a federal lawsuit seeking to compel the U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs to enforce her tribal voting rights.

She remains hurt and indignant that the Cherokee Nation will not acknowledge her roots.

On a recent visit to Tahlequah, she stopped by tribal headquarters, a concrete building emblazoned with the words “Welcome to Your Cherokee Nation” in English and Tsalagi. Although it was closed, she was wary.

“I don’t want to get spotted by the security camera,” she said, shooting glances over her shoulder -- still an outsider in a world she has known all her life.