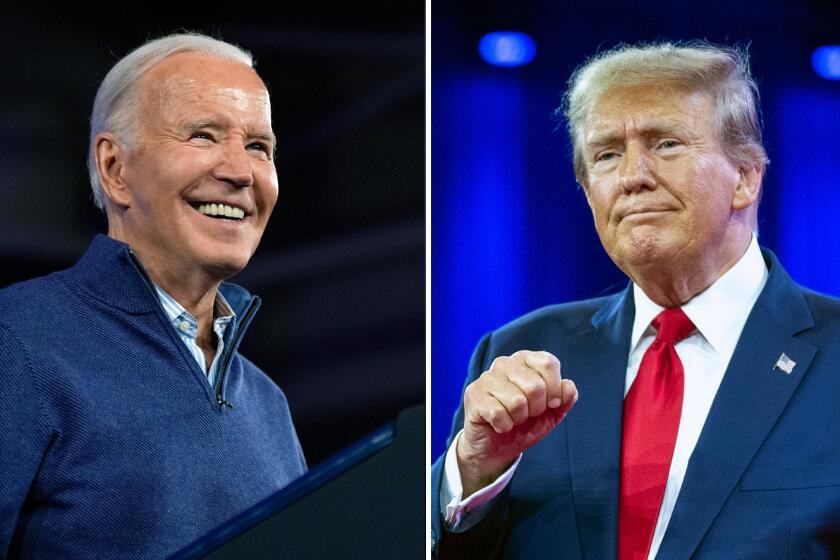

Column: Biden is old. Trump is too. But only one of them would trash the Constitution

- Share via

WASHINGTON — President Biden’s age was back in the news last week, thanks mostly to a front-page article in the Wall Street Journal announcing: “Behind closed doors, Biden shows signs of slipping.”

The story was less sensational than the headline. It quoted Republican Kevin McCarthy, the former House speaker from Bakersfield, as saying the president “is not the same person” that he was a decade ago. It quoted the current speaker, Mike Johnson (R-La.), as saying that Biden, in a meeting, “appeared to misunderstand” his own policy on natural gas.

But here’s a Washington secret you already knew: McCarthy and Johnson, bitter opponents of the Democratic president, aren’t reliable narrators here.

The real story is both obvious and elusive. At 81, the president is showing signs of his age. He walks unsteadily thanks to spinal arthritis. Once voluble, he now sometimes gets words tangled when he speaks. He often gets names and details wrong, although he’s done that for years.

“What you see on TV is what you get,” Republican Sen. Jim Risch of Idaho told the Journal. “These people who keep talking about what a dynamo he is behind closed doors? They need to get him out from behind closed doors, because I don’t see it.”

Freed of responsibilities as speaker, the Bakersfield Republican can devote himself to what’s long been his forte: campaigns and elections. Payback is part of his agenda.

That sounds about right. Democrats in Congress say things like that, too, just not for quotation.

But none of that quite proves that he’s no longer up to the job — and that’s the important question.

In a long interview with Time Magazine published last week, Biden sounded, again, pretty much as he does on television. At one point, he said “Putin,” the name of Russia’s president, when he appeared to mean China’s Xi Jinping. At three points, the transcript says the president’s words were “unintelligible.”

Yet on matters of substance, he was entirely cogent, often at a detailed level, explaining his policies on Russia and Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, and China and Taiwan.

Immigration order provides further evidence that the president is willing to risk significant dissent within his party to woo back moderates.

Asked whether he thinks he’ll be able to do the job at 85, he bristled combatively, just like the young Biden. “I can do it better than anybody you know,” he said.

It has become a recurring cycle. In February, special counsel Robert Hur described the president as “a well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” Biden erupted with fury. “I know what the hell I’m doing,” he said.

A few weeks later, he delivered a feisty State of the Union speech, and the “age issue” seemed to ebb — for a while.

It’s as if he’s trapped in an election-year version of the myth of Sisyphus, condemned to push the boulder of his years up a hill only to watch it roll down again.

There’s a simple reason the issue won’t go away: Biden is the oldest man ever to serve as U.S. president, and the oldest to seek a second term. That guarantees that voters will have qualms.

A New York Times/Siena College poll in April reported that 69% of voters think Biden is too old to be an effective president.

Column: Trump and Biden both think they can land a knockout in the debates. They can’t both be right

President Biden and Donald Trump both think they can win debates, and the 2024 election, by spotlighting each other’s flaws. They can’t both be right.

His Republican opponent, Donald Trump, did considerably better; only 41% said they think Trump is too old.

Trump is three and a half years younger than Biden. The former president turns 78 on Friday.

And Trump’s flaws are at least as numerous as Biden’s.

He, too, mixes up names and places. In recent months, he has frequently said “Obama” when he meant “Biden.” He repeatedly confused Nikki Haley with Nancy Pelosi.

He has a hard time pronouncing multisyllabic words (“anonymous,” “infrastructure,” “origins”). His speeches ramble from one seemingly disjointed thought to another.

And he often says things that are either wildly false, like his claim that he created the strongest economy in American history (not even close) — or nonsensical, like his warning that if Biden wins, “they’re going to change the name of Pennsylvania.”

Donald Trump isn’t telling you what he thinks about abortion, Obamacare and the federal budget. Why? Because it won’t help him beat Biden in the election.

So why does Trump benefit from what looks, at least to Democrats, like a double standard?

For one thing, he’s steadier on his feet than Biden, and some voters seem to use that as a measure of overall fitness.

But physical agility isn’t essential to presidential success. Franklin D. Roosevelt did the job from a wheelchair.

Biden’s stiff gait is visible every time he walks across a stage or a parade ground. Trump appears more vigorous, at least at first glance. But we don’t actually know which of them is in better physical condition. Biden’s medical report, which pronounces him “fit for duty,” is six pages long and includes his weight, his blood pressure, his medications and details of his conditions. Trump’s report is one page long and includes none of that information.

A second explanation: low expectations. Voters have grown accustomed to Trump’s zaniness.

When a reporter recently asked Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) to explain some of the former president’s oddball statements, Graham offered an all-purpose explanation: “Give me a break. I mean, it’s Trump.”

Biden and Trump offer converging narratives about the country: one optimistic, one apocalyptic. That collision is the core of the 2024 election.

A related theory: brand consistency.

“Biden ran for president on a platform of stability and competence, and that image is undermined by suggestions of mental decline,” McKay Coppins of the Atlantic wrote recently. “Accusing Trump of going crazy doesn’t work because, well, he has sounded crazy for a long time.”

The sobering fact is that we don’t have a reliable way to gauge the mental acuity of either candidate.

Biden and his aides argue that he ought to be judged by the results of his first term: the bills he has passed, the alliances he has maintained, and the strong economy he has produced (even though it has come with chronically high prices).

That’s a reasonable measure, except it gauges the last three years, not the next five.

Trump was asked whether the election would end in political violence if he lost. “It depends,” the former president said. Here’s what he meant by that.

A better solution might be the one Haley, the former South Carolina governor, proposed when she ran against Trump in the GOP primaries: Subject both candidates to a cognitive test.

“They should both take the test, along with every other politician over the age of 75,” Haley said. “Voters deserve to know whether those who are making major decisions … can pass a very basic mental exam.” (She also said she thought Trump was “diminished” and “not the same person he was in 2016.”)

But neither candidate has embraced that idea. And at least one of them would undoubtedly claim the test was rigged if he flunked.

Trump submitted to a cognitive examination six years ago and bragged that he‘d “aced” it, although he did not release the actual results. The test, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, is widely used to screen patients for symptoms of dementia.

The media have a part to play by taking more hard looks at both candidates — beginning, perhaps, with a Wall Street Journal story on Trump.

The problem is not that we have an elderly president who’s less crisp and coherent than he used to be. It’s that we have two elderly candidates, both of whom are less crisp and coherent than they used to be.

One is unsteady on his feet. The other is a serial liar who thinks the Constitution allows him to overthrow elections and jail his opponents.

No wonder voters are dissatisfied.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.