- Share via

HEMET, Calif. — Douglas Frank grinned as a high-pitched whine filled the sanctuary of a small Hemet church.

Holding an aluminum rod he said represented America, Frank quickly passed his fingertips over the metal, causing it to vibrate and build resonance.

The whine grew into a howl.

“There are lots of us patriots going around the country spreading truth in America. And while we’re spreading the truth ... it’s resonating,” said Frank, who left his job as an Ohio high school teacher to make scores of presentations across the country falsely claiming the 2020 election was rigged. “And it’s getting louder, county by county, state by state around the country.”

Frank’s demonstration followed a frenetic speech filled with baseless claims about suspicious voting trends and secret algorithms used to steal elections. He proposed a strategy for pressuring elected officials through protests and packed public meetings to abandon the use of election machines or resign.

“Problem with the truth is it’s annoying,” Frank said above the din, his audience of about 75 predominantly white, elderly attendees flinching from the noise made by his prop. “I can make this thing scream. I can make it unbearably loud. And you need to make the truth unbearably loud.”

Frank is convinced that American elections need saving and believes that to do so, people must take back the ballot box one county at a time. And though his allegations have been disproved and dismissed by election experts and fact checkers, he hasn’t been deterred from spending the last 2½ years on the road, spreading his message to any group that will host him.

“I’m fighting for the country that I grew up in that’s no longer here,” Frank said in an interview with The Times.

Breaking the Ballot

A Times series on how election misinformation spreads in America.

His more than 50 speeches in California and hundreds more across the country are part of a multi-pronged effort by the election denial movement to make a significant impact on future elections by changing state laws, training candidates and — in Frank’s case — organizing volunteers to challenge local results and voter rolls.

Paul Gronke, director of the Elections & Voting Information Center at Reed College in Portland, Ore., called Frank’s theories “fiction.”

“He’s a compelling presenter, but that doesn’t change the fact that what he’s saying are not facts,” Gronke said.

The morning of the Hemet event, Frank was hours away in Orange County, training activists how to uncover alleged election fraud. He spoke at a barbecue there the night before.

The next day, he held several events in the Central Valley and met with local officials. The day after that, he received a progress report from one of his local teams and gave a nearly two-hour talk to about 70 San Joaquin County residents at an Acampo Moose Lodge.

Frank’s decision to focus on deep-blue California may seem illogical. But when Shasta County, a conservative stronghold of 180,000 people, decided to stop using election machines, it drew national attention — and, Frank says, interest from activists who believe in his cause.

“People that I work with around the country were saying, ‘Well, gee, why are you spending all that time in California? You’re never going to be able to get anything to happen there,’” Frank said. “Now California is maybe one of the most important states and now they’re all saying, ‘Gee, when’s the next time you’re going to be out there?’”

How a team of cyber experts and lawyers came together in the days after the 2020 election to try to find information suggesting fraud, in an attempt to keep Trump in office despite his defeat.

Frank said he got involved in Shasta County’s efforts last fall. Local activists had already been knocking on doors to conduct their own election audit and were pressuring county supervisors to stop using Dominion Voting Systems machines. Sympathetic county supervisors were elected to the board in November and Frank visited the county several times to present his election fraud theories.

He said he “coached” some of the supervisors on strategy in daily phone calls and private meetings. The Shasta County Board of Supervisors ended its contract with Dominion in January and went a step further in March when it voted to stop using electronic machines to tabulate ballots. Only a small number of the roughly 10,000 election jurisdictions in the U.S. have stopped using electronic voting machines since 2020.

Frank speaks of Shasta County in biblical terms, holding it up to audiences as an inspiration and template.

“Once David slew Goliath, then the Hebrew children, the Israelites, chased the Philistines out of the land. ... They suddenly all got brave, right? Shasta just slew Goliath. Now you all need to get brave,” he said in Hemet.

Election officials are worried Frank’s claims are being embraced by people who feel disenfranchised and oppose efforts to expand voter registration and voting by mail.

“Doug’s got the ability to persuade people to believe in the philosophy he’s trying to share,” Kings County Registrar of Voters Lupe Villa said. “There’s going to be people that are going to believe in that, and that can be very dangerous for a lot of us. It can be very dangerous to our democracy.”

An outsize amount of Frank’s travel has been to California.

Social media posts by Frank and associated so-called election integrity groups indicate he has made about 50 presentations at churches, bars, libraries and civic organizations in the state over the last year. Frank also holds private training sessions to teach local teams how to canvass and look for fraud, and presents his theories to sheriffs, registrars of voters and county supervisors when possible.

He made a 12-day swing through California in May. The next month, he appeared at an election reform conference in Rossmoor and spoke in Laguna Hills to a San Clemente Republican women’s group. Groups in the state have booked him multiple times over the next several months, including a Friday event in Lodi headlined by Donald Trump’s ally Kari Lake, who ran an unsuccessful campaign for Arizona governor last year.

Life on the road gave rise to a new nickname, Frank said: the “Johnny Appleseed of election fraud.”

“Instead of planting apple seeds, I think I’m going around starting little fires everywhere,” Frank said. “And then I come back and I throw gasoline on those fires.”

——

Frank is among a loosely linked network of people and organizations whose unfounded belief that fraud cost former President Trump the 2020 election has fueled a mission to disrupt how Americans vote.

Known as “Dr. Frank” to his supporters, he was born and raised in Sonoma County, studied chemistry at Westmont College in Santa Barbara and earned a doctorate in surface analytical chemistry from University of Cincinnati. Before transitioning full time to giving election fraud speeches, Frank served as chair of the math and science department at a Cincinnati private school.

Frank first got involved in trying to find fraud after the 2020 election, when he said he was among a handful of people asked by Trump supporters to look at Pennsylvania’s results. His work drew the attention of MyPillow Chief Executive Mike Lindell, who helped raise Frank’s profile. Since then, Frank has appeared in Lindell’s election conspiracy films, is a frequent guest on Lindell’s streaming show and has emceed Lindell’s election denial conferences. In June 2021, Frank spoke at a televised rally for Trump in Ohio.

Frank has said that, like Lindell, he had his phone taken by the FBI. He said it happened in September 2022 as he stepped off a plane in Denver, and attributed it to his involvement in persuading former Mesa County, Colo., clerk Tina Peters to allow election deniers to copy restricted election information that was later widely shared online. (The agency has confirmed that a warrant was served in the Denver area, but typically does not provide further information unless charges are filed.) Peters was indicted last year on state charges of election tampering and official misconduct. Her trial is scheduled for October. Frank has not been charged in that ongoing case.

Federal law enforcement doesn’t appear to be investigating the former president’s allies’ attempts, some successful, to access election machines. Experts are alarmed.

Frank spent 2021 trying to convince state lawmakers and secretaries of state that he had evidence of fraud. When officials dismissed or ignored his claims, he began building a network of self-styled election integrity teams in an attempt to find evidence of fraud across the country, including in several California counties.

In addition to pushing counties to stop using election machines, which he believes are susceptible to manipulation, Frank wants to end vote by mail in most circumstances and supports hand-counting all ballots, something states haven’t done on a large scale in at least 50 years. Many states, including California, perform partial audits or recount close races by hand. But Shasta is the only county in the state that has opted to count all ballots by hand.

Frank’s intensive travel schedule distinguishes him from election conspiracy theorists who primarily deliver their message online. Unlike those evangelizing keyboard warriors, he proselytizes in person to relatively modest crowds at community and civic centers, and is directly involved in setting up local teams of activists to investigate alleged voter fraud.

Stanford University political science professor Justin Grimmer, whose work debunking Frank’s claims has made him the election denier’s primary foil, said he has focused on Frank in part because he doesn’t fit the expected mold.

“He is going place to place, small town to small town, giving the same talk, organizing people in the same way, applying pressure to these local officials who are then feeling the pressure in a way that other folks working in this space, who are advancing these sorts of fraud conspiracies, just either don’t have the resources or time to do,” Grimmer said.

In May, Frank took his presentation to a dive bar in Sherman Oaks, a church in Rancho Cucamonga, a public library in Palos Verdes and a theater in Ramona. Previous California speech venues included a Sizzler in Fullerton, a Mentone steakhouse, an El Segundo public library, a Laguna Niguel shooting range, the Clovis Memorial Hall and the Sunset Hills Country Club in Thousand Oaks.

At the end of his events, organizers ask for donations to help pay for his travel costs. Frank said that he does not charge for his appearances and that he covers some of the cost out of pocket, but it is unclear whether he receives other help covering his expenses.

Frank explains his California focus by saying that conservatives in the state already know something is off and are open to his message. He told The Times that his audiences are shocked that the effort to recall Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom failed and are unhappy with the policies coming out of Sacramento.

“You’re already awake because you have your state government kicking your beehive every day, right?” Frank said to an assembled group in Hemet, who erupted in peals of laughter.

Also key, he said, is the sheer population of California counties. Swaying a single California county to stop using machines or to clean its voter rolls affects more people than implementing those changes in some states.

“The counties here are as big as the states. L.A. is bigger than most states in the country,” he said.

His first invitation to speak in California came in July 2022 from a group that aims to split the Democratic stronghold into multiple states.

Attendees of Frank’s first speeches in California formed groups that now assist him. One of them, God, Guns, Government, books his appearances and handles his public relations in the state. Patriot Force CA President Urson Russell drives Frank around when he visits, and his group trains local teams how to canvass and implement Frank’s playbook.

“He’s putting his heart into this because the people are waking up and asking for some direction,” Russell said.

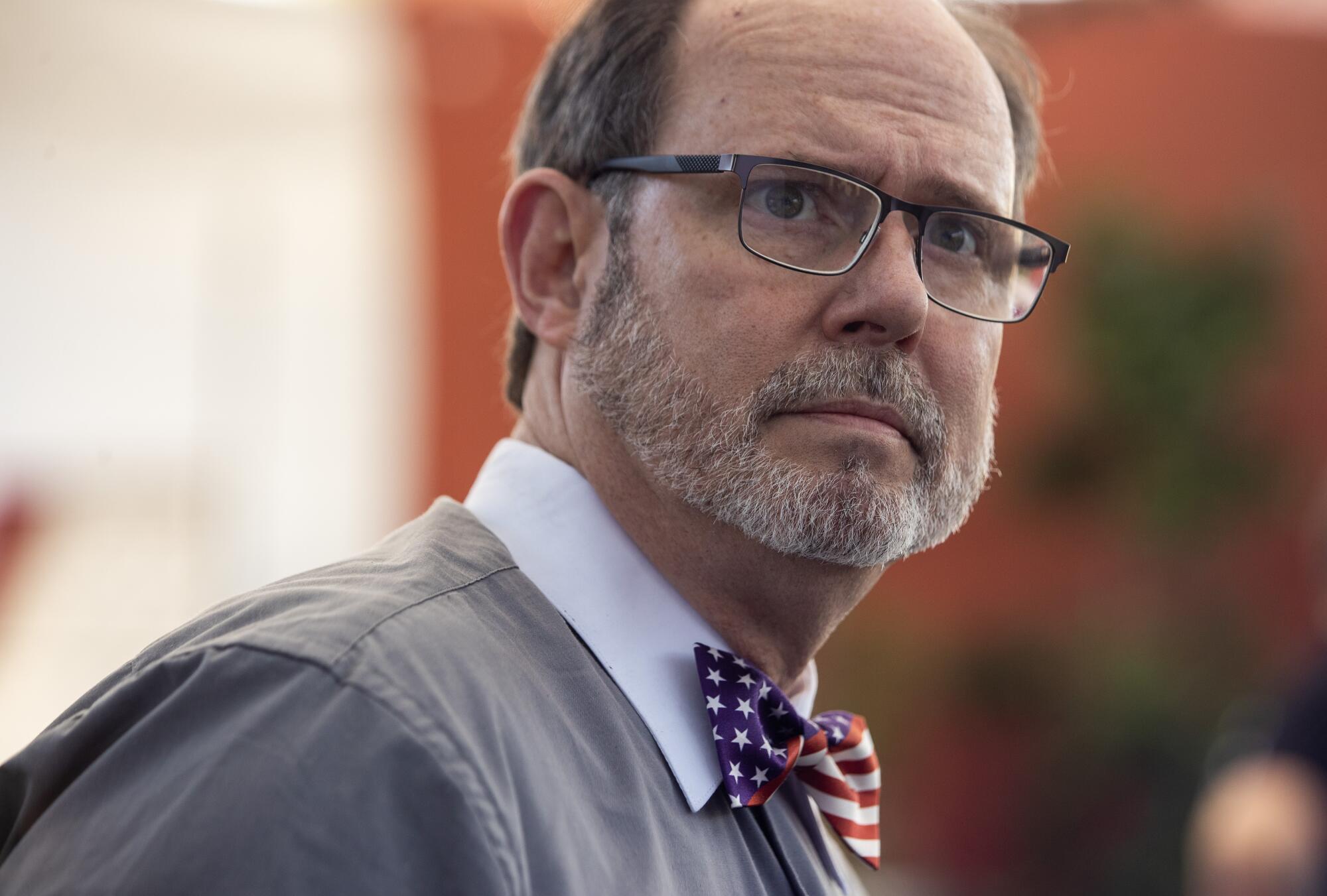

Frank’s presentation consists of lengthy stories about his background, his work in other states and with prominent right-wing figures. Always wearing a bow tie, he peppers his presentation with jokes, pop culture references and MAGA terms. He tells people to stop watching Fox News and rely on One America News Network and Lindell’s show.

His speeches assume his audience is steeped in false conspiracy theories, including that local sheriffs have more power than the state or federal government, a key component of his plan to stop counting ballots electronically.

Pinning alleged election fraud on an unnamed “they,” Frank dances around identifying who he thinks is manipulating elections. When pressed, he names a national nonprofit organization that provided election administration grants to thousands of local governments during the COVID-19 pandemic, and people who worked for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

“Until you take back the ballot box, your liberty is at risk,” Frank said.

It’s harmful for Frank to link taking action on his theories to protecting liberty, said Gowri Ramachandran, senior counsel in the Brennan Center’s Elections & Government Program.

Frank and his contemporaries have achieved less than they claim, she said. County officials often abandon plans to stop using election machines when they learn how much it will cost or that their actions would violate state law.

“There’s a lot of ... touting of success. And, you know, trying to try to build momentum to do something that is, it turns out, really, really just impractical to try to implement,” she said.

——

Frank’s hourlong to two-hour presentations dedicate little time to explaining where his data come from or how he reached his conclusions. The explanation of his analysis of election and voter data from California and Riverside County made up about 10 minutes of the nearly two hours he spoke in Hemet.

The speed at which Frank whips through his slideshow makes it nearly impossible to absorb the information.

He claims estimates of how many people will vote by age bracket constitute evidence of widespread fraud. He alleges that voter rolls are inflated because registration has outpaced estimated population growth. And he rattles off mathematical terms such as “correlation coefficient” and “sixth order polynomial” that might not be familiar to his audience. He repeatedly skips details that would explain how he reached his conclusion, instead telling attendees that what he found simply “ain’t natural, buddy.”

Frank told The Times that the data he used are publicly available and came from the U.S. Census Bureau, the California secretary of state’s office and various county registrars of voters, but he wouldn’t name the data sets for verification.

Grimmer, the Stanford professor who has studied and published papers about mathematical flaws in election denial theories, said Frank uses faulty equations and common statistical tricks in his analysis to present misleading conclusions.

“He dresses it up in a variety of ways. Some of those are red herrings. Some of that’s for the audience. Some of it is perhaps I don’t know if he knows what he’s quite doing,” Grimmer said.

Local officials have regularly asked Grimmer to counter Frank’s presentations, including in Shasta and Placer counties. That prompted him to build a website compiling data for 2,800 counties across the country to help them respond to Frank’s claims.

Grimmer said he watched videos of 10 Frank presentations before he was able to piece together where the data come from and how Frank reached his conclusions.

“Like a lot of people who are advancing these election fraud claims … [Frank didn’t] write up a nice academic paper that says, here’s where we got the data, here’s our statistical methodology, here’s our replication code,” Grimmer said.

Grimmer and his colleagues have submitted an article on flaws in Frank’s methodology and reasoning to Election Law Journal for peer review. Grimmer invited Frank to respond to their findings in December, sending him multiple requests. Frank told The Times in May that he would post a public response to Grimmer within a few days, but has not.

Frank mentions Grimmer in his presentations, calling him “this guy who’s never even left his stupid cubicle at Stanford.” He recounts the snarky comments he made about Grimmer’s statistical methodology when Grimmer testified about whether Frank was qualified to serve as an expert witness in an Oregon lawsuit.

What Frank doesn’t tell audiences is that the judge ruled he did not qualify.

Frank told The Times that Grimmer is too focused on the numbers and doesn’t address the alleged fraud that local teams find.

“I use the statistics that he’s talking about not as proof, I use the statistics as a smoke to find the fire. [Grimmer is] all hung up on the statistics, but he’s missing the whole point,” Frank said.

Placer County Registrar Ryan Ronco, who leads the California Assn. of Clerks and Election Officials, brought Grimmer and Frank together after learning that Frank made a presentation at a Lindell event that cited an analysis of Placer County’s elections and voter registration.

Ronco said anyone with concerns over election accuracy — including Frank — deserves an explanation of how the process works and why their information is wrong.

“At the end of the day, if your concerns are not valid, then you probably need to at least admit that the concerns were not founded,” Ronco said. “I don’t think that Dr. Frank is there yet.”

——

Frank warns his audiences against running to local elected officials in response to his presentation, saying they’ll be blown off as “conspiracy wingnuts.”

Instead, he encourages them to first follow the methods he’s outlined to find fraud so they can’t be dismissed. But, he reminds them, “it’s your fight, not mine.”

“I’m the arms dealer. And I’m coaching you and I’m helping you and I’m happy to fight alongside you when you need me,” Frank said at a Utah team planning meeting that was posted to his Telegram account and to Rumble, a video-sharing website popular with election deniers.

In meetings that aren’t publicly advertised, Frank lays out a multi-step plan to build a local team. He encourages attendees to connect with groups that push disinformation about election fraud for coaching and resources used by professional political campaigns, such as the national change of address registry, the local death master file and voter registration rolls.

Frank instructs the teams to study state laws and regulations to tailor plans to their locality. He tells them which county officials to build relationships with, how to analyze voter data to identify alleged fraud — he cites as examples ballots returned for people who have died or moved out of state — and how to organize teams to knock on doors and ask questions. He details how to collect affidavits attesting to claims of fraud and prepare supporting documentation.

The next step for the team is to ask the local sheriff to open a case and investigate what they’ve found. Then, with a case number in hand, they begin putting pressure on county supervisors, Frank said.

“You go in there and you say, ‘I found fraud with my own hands and feet,’” Frank said to the Hemet audience. “You see how that works? See the difference between screaming bloody murder about fraud and having it in your hand? It’s a tremendous, empowering thing.”

Frank said five California teams have case numbers from local sheriffs and are preparing to demand that elected officials stop using election machines, but he would not identify them.

At his Acampo Moose Lodge presentation, Frank told attendees that San Joaquin County is poised to follow Shasta’s lead.

In February, Lodi City Councilmember Shakir Khan was arrested and accused of multiple felonies after the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office alleged that 41 mail-in ballots were found during a search of his home and about 70 names were registered to Khan’s home, his email or phone number. Khan’s first pretrial conference is in September, according to court records.

Frank told the audience the arrest came in part because the local team identified potential fraud and notified the sheriff.

As his speech wound down, Frank pulled out the aluminum rod. A familiar metallic wail enveloped the room.

“We have to stop being sweet, polite Republicans and we have to say we’re not going to tolerate our elections getting stolen from us anymore,” Frank said as applause began to drown him out. “You got to make [it] loud. You got to make it unbearable.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.