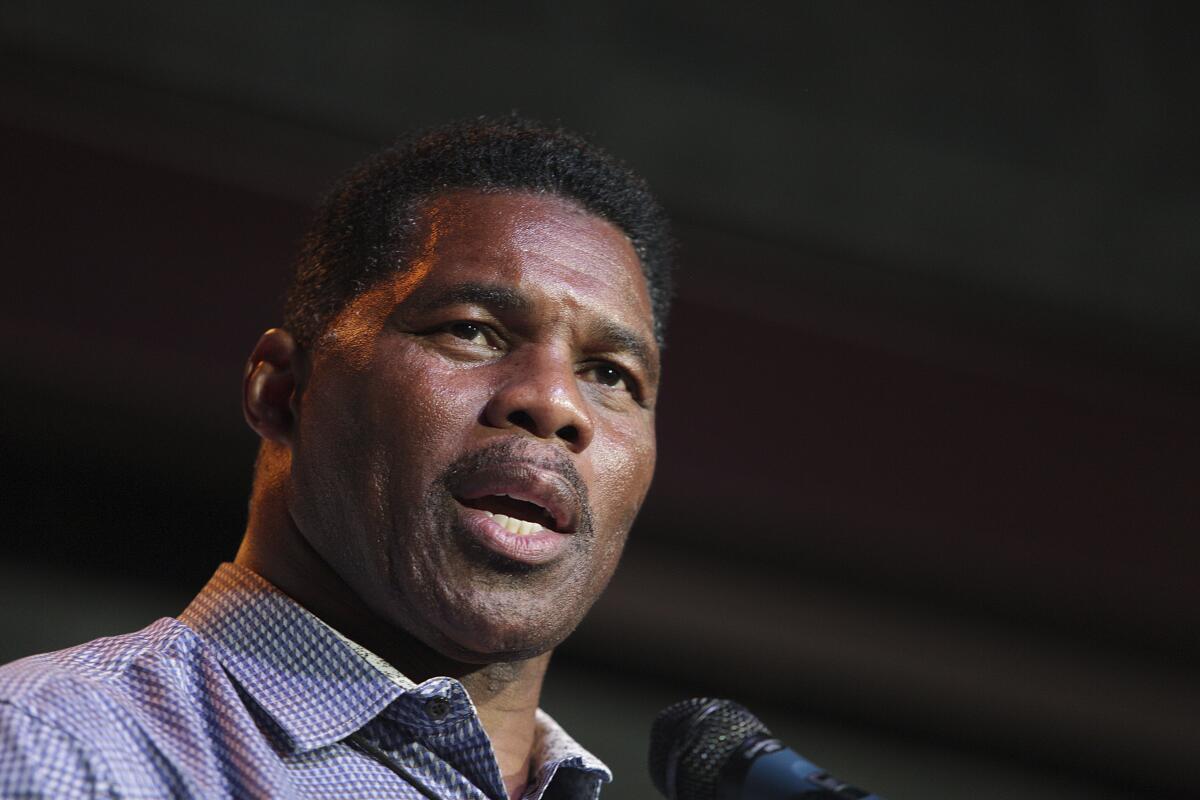

Herschel Walker and Raphael Warnock head to runoff in Georgia Senate election rife with controversy

In Georgia, Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and his Republican challenger, Herschel Walker, are headed for a Senate runoff election next month.

- Share via

ATLANTA — The Southern battleground state of Georgia is headed, once again, for a bitterly contested Senate runoff election as results show Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock narrowly leading his Republican challenger, Herschel Walker, according to state election officials. Neither candidate is on track to secure 50% of the overall vote in the election that included Libertarian Chase Oliver.

Warnock and Walker are now set to face off in a Dec. 6 runoff, less than two years after Warnock became the first Black senator from Georgia in an intense and nationally followed runoff that was one of two races that determined control of the Senate. Back then, Warnock was part of a historic blue wave that saw voters in this traditionally conservative stronghold elect President Biden and two Democratic senators.

Now, as then, political control of the Senate hangs in the balance. Republicans on Wednesday held a 49-48 lead in the battle to control the Senate, with races in Arizona and Nevada also yet to be decided.

In a brief speech to supporters Tuesday night at a hotel in Atlanta’s northern suburbs, Walker referenced “Talladega Nights,” the movie starring Will Ferrell: “I’m like Ricky Bobby: I don’t come to lose.”

Just before midnight, Warnock told supporters gathered in a downtown Atlanta hotel ballroom that the race was too close to call and asked them to hang on a little longer.

“We know how much is at stake in this election,” he said. “I’m going to say to you what I say to my church every Sunday: Keep the faith and keep looking up.”

Not only did Trump-backed candidates lose key races, but his biggest GOP rival, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, won handily. It was a bad night for the former president.

Before 2 a.m., Warnock reemerged to tell a smaller crowd that he was still not sure when the journey would end.

“I understand that at this late hour you may be tired. I may be a little tired,” he said. “But whether it’s later tonight, or tomorrow, or four weeks from now, we will hear from the people of Georgia.”

On Wednesday, managers for the two campaigns lost little time in taking to social media to snipe at their opponents’ shortcomings.

Warnock campaign manager Quentin Folks noted on Twitter that Walker “significantly underperformed,” earning 200,000 fewer votes than Gov. Brian Kemp and less than every other statewide Republican on the ballot.

Former President Trump’s dominant role may have cost the Republican Party in the midterm elections, but he’s unlikely to walk away quietly.

His counterpart, Walker’s campaign manager Scott Paradise, suggested in turn that Warnock had failed to make the most of his advantages: “More than 50% of Georgians voted against the incumbent that spent more than $100 million.”

This year, the Georgia Senate race tested Republican loyalty to a problematic candidate — Walker, a former football star, has a history of lying and embellishing — amid preelection signs of voter disillusionment with Biden and the Democratic Party.

Throughout the campaign, Democrats had hoped Walker’s political inexperience, along with his propensity for gaffes and false claims, made him a liability that would block Republicans from reclaiming this pivotal battleground seat. The campaign by the Heisman Trophy-winning University of Georgia running back, NFL star and multimillionaire businessman was rocked by multiple scandals and allegations that he encouraged and paid for multiple women to terminate their pregnancies, despite his support for a national ban on abortion.

Voters in Michigan have enshrined abortion rights in the state’s constitution, matching the success of similar measures in California and Vermont.

Walker, who was backed by former President Trump, also embellished and lied about his record, falsely claiming he worked for law enforcement and bragging that he was “in the top 1%” of his college graduating class though he did not graduate.

In the closing days of the campaign, Warnock, who continues to serve as senior pastor at the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s former church, Ebenezer Baptist, assailed Walker as a “pathological liar.”

“This is a man who lies about the most basic facts of his life,” Warnock said at a rally with former President Obama. “Walker is not ready. … Not only is he not ready. He’s not fit.”

Polls showed Walker trailing in the months ahead of election day, but then closing the gap in the final stretch of the race. His performance in his only debate with Warnock, in mid-October, passed without any major mistake. Walker repeatedly linked Warnock with Biden and played up the issues of inflation, immigration and crime.

In one of Walker’s final TV ads, his campaign accused Biden and Warnock of “radically changing America,” steering the country into recession, opening its borders, defunding the police and teaching children to hate America. “Not on my watch,” Walker said.

In an age of tribalization, are there limits to party loyalty? Could Herschel Walker, urged to run by Trump, cost Republicans control of the Senate?

Warnock and Walker worked to drive turnout among their base and appeal to more moderate voters in the suburbs who leaned Republican but were turned off by Trump and voted Democratic in the last election cycle. They also worked to court Black men, a traditional segment of the Democratic voting bloc with whom Republicans have made gradual inroads in Georgia in recent years. In recent months, Walker’s campaign played up culture war issues, airing radio ads and sending out mailers that targeted Black men with accusations that Warnock and Democrats wanted to let boys play girls’ sports.

More than 2.5 million Georgia voters voted early, a record-breaking turnout for a midterm.

The tightness of the race was not so much a sign of the weakness of Warnock’s campaign as an indication that Georgia still leaned red, said Fredrick Hicks, a Democratic political strategist based in Atlanta.

“Historically speaking, it’s a minor miracle that a Black Democrat beat a white Republican last year and that he was close to ahead this year,” Hicks said. “This is still Georgia.”

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.