Column: Amid tribalism and polarization, an unpredictable election underscores the country’s jittery mood

- Share via

America has known hard times. War. Depression.

How today’s anxieties compare is, for most people, irrelevant. All that matters is we’re living in these fraught times, and if history shows the country has weathered far worse, it’s little solace.

Inflation gnaws at our paychecks. Fear of crime fills many with foreboding. The right to abortion once guaranteed under the Constitution has suddenly vanished and other rights, like same-sex marriage, appear newly open to interpretation.

Under the weight of those worries, our political system quavers.

Candidates focus less on broadening their support than urging their most rabid followers to the polls. Tribalism has grown so deep that, however flawed a candidate, some would sooner lose a limb than cross over and support a member of the opposite party.

Obscene sums of money finance a ceaseless barrage of advertisements that rake our senses raw. What passes for debate is shot through with gleeful malice; for some on the right, the attempted assassination of the Democratic House speaker and the brutal assault of her husband were not horrifying but the butt of a joke.

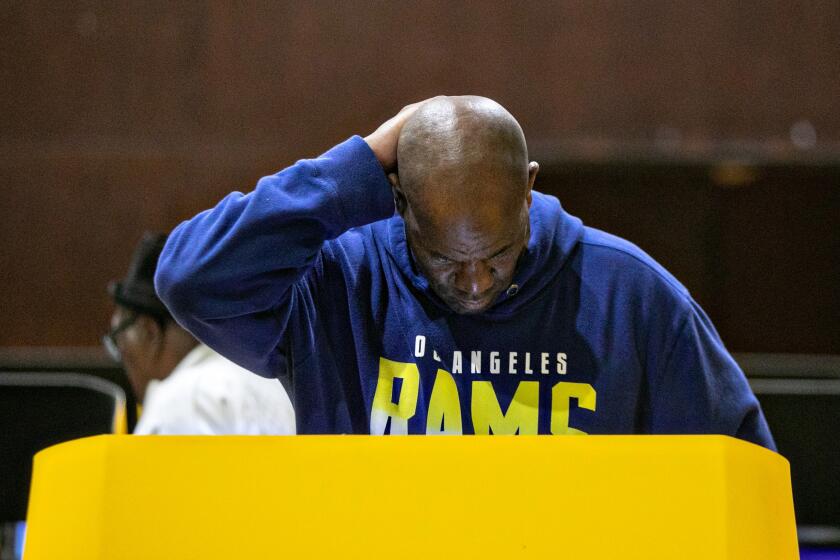

Voters across Southern California braved the rain Tuesday to cast their ballots

Most troubling, the very foundation of our democratic republic — the conduct of free and fair elections and a willingness to adhere to the result — can no longer be taken for granted, as a goodly portion of Republicans willfully refuse to recognize the president’s clear-cut 2020 victory. Some of the loudest voices in the party — echoing the party’s mendacious leader-in-exile — recklessly persist in sowing unfounded doubts about our voting system.

In a deeply divided nation, the one thing unifying Americans is a shared sense of unease. Vast majorities feel the country is heading in the wrong direction, but fewer agree on why that is -- and which political party is to blame. This occasional series examines the complicated reasons behind voters’ decisions in this momentous and unpredictable midterm election.

David Kennedy, a Stanford historian, has written masterful works on some of the country’s worst hard times, including the Great Depression. In some ways, he said, what is happening today is even more unsettling.

The Depression, he said, was an abrupt shock that emboldened the country’s leaders and fostered creative and lasting change that improved the lives of countless millions. “What we face today is not so much a shock as a culmination of a lot of things that have been festering and building and gathering momentum and strength for at least a generation, if not a little bit longer,” Kennedy said.

Among them, he cited globalization, which has economically displaced huge numbers of Americans, and the failure of a polarized, fratricidal political system to adequately respond to the loss of livelihoods and what, for many, was a reassuring way of life.

The result of Tuesday’s election seems unlikely to produce the changes — more cooperation, greater compromise, a less toxic political atmosphere — that many voters profess to want.

“We’re dug in,” Kennedy said. “Polarization means paralysis. Paralysis means you don’t go forward.”

::

If history is a guide, Democrats’ nominal control of Congress is about to end.

Republicans need to pick up just five seats to gain a majority in the House. In all but three midterm elections since the start of the Civil War, the president’s party has lost seats. The average over the last century is 28.

That’s because midterms are almost always a referendum on the incumbent, with the likeliest voters being those who are discontented with the status quo.

In Arizona, the bedrock issue of free and fair elections is on the ballot as Trump acolytes vie to seize the state’s election machinery.

With inflation gone wild and fears of a recession growing, President Biden’s approval ratings are mired in the mid-to-low 40% range. That suggests plenty of unhappiness looking for an outlet.

The fight for the Senate, which is split 50-50, appears less certain. The party in the White House has lost Senate seats in 19 of 26 midterms since the direct election of senators began in 1914. The average loss over the last century is four seats.

Because they run statewide, and not in districts larded with voters of one party or another, Senate candidates have typically been judged more on individual merit and through the quality of their campaigns. But that may be changing.

“Democrats are all motivated to vote for the Democrat and Republicans to vote for the Republican,” said Charlie Cook, who has spent decades handicapping elections for his eponymous and nonpartisan campaign guide. “I expect very few defections.”

With the two parties nearly evenly matched, that means several contests could go either way and, with them, control of the Senate. Whether Democrats or Republicans are in charge, neither party is likely to command an overwhelming majority when the next Congress is sworn in.

As 2022 midterm election comes to a close, Republicans project optimism, as Democrats are hurt by voter dissatisfaction over Biden and the economy.

Political professionals have a term for the dynamic that drives elections in today’s pungent climate. It’s called negative partisanship. Simply put, many voters may not be particularly thrilled with the choices offered by their party, but they fear or loathe the candidates running on the other side even more.

Thus, as thoroughly incompetent and truth-challenged as Herschel Walker appears to be, the overwhelming majority of his fellow Georgia Republicans will probably vote to elect him rather than support incumbent Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock. As worrisome as the health of John Fetterman appears — the lingering effects of a stroke he suffered in May being painfully manifest in a debate last month — the overwhelming majority of his fellow Pennsylvania Democrats are virtually certain to back him for the Senate over Republican Mehmet Oz.

Opting for what seems the least-bad choice — a default that has become familiar to many voters — has spawned a persistent lack of faith in our elected leaders, a sentiment that has steadily grown since the Vietnam War era.

In the 2022 midterm election, control of Congress is at stake, as well as key gubernatorial and statewide races. Here’s what to know.

A recent NBC poll found that fewer than half of those surveyed said they always or mostly trust their governor and only a little over a third said they trust the president or their representative in Congress.

That contemptuous attitude is hardly surprising when so many voters cast their ballot with one hand while holding their nose with the other.

::

If, as seems likely, the House flips, it will continue a pattern of political volatility that has been a hallmark of this still-young century.

Starting in 1960, there were three elections in 18 years in which control of the White House, Senate or House switched parties. There were four over the next 18 years. Since 2000, there have been nine elections in which power shifted. Tuesday’s balloting could mark the 10th.

There are several reasons for the accelerated turnover.

The internet makes fundraising easier than ever, producing more viable candidates.

The two major parties tend to overreach once they gain power, inviting a backlash from remorseful voters.

Not least is the rough parity between the parties and the ideological sorting — bluer blues, redder reds — that have driven Democrats and Republicans further apart and made their respective partisans increasingly vote in lockstep.

Democrats are on defense as Republicans try to wrest control of the House and Senate in the Nov. 8 midterm elections. Here’s what you need to know.

Lynn Vavreck, a UCLA political science professor, has co-written a new book in which she describes the “calcification” of our politics. Seismic events occur — a once-in-a-century pandemic, a historic reckoning for generations of racial discrimination, an attempted coup aimed at overturning the 2020 election — and they do little to alter the political equilibrium of a split-down-the-middle America.

Given that balance, a small shift in the electorate every two years has resulted in one or the other party gaining power in Washington.

“Calcification doesn’t mean we’re stuck with the same party winning every election,” Vavreck said. “It means we’re stuck on the knife’s edge and we’re just tilting one way, the other way, one way, the other way.”

If change is what voters want — an end to the blood-sport nature of today’s politics, a more reassuring sense of stability in Washington — it doesn’t appear in the offing.

But there is, as Vavreck suggested, one hopeful glimmer as we close this acrid election season.

“Let’s say the candidates who lose, whoever they are, concede their election outcomes. They do what we’re used to candidates doing, which is ... thank their supporters for working hard and say something like, ‘Let’s give the other guy a shot. He won fair and square.’ That’s a huge, huge step in the right direction,” she said.

“If that doesn’t happen,” Vavreck went on, “it’s very bad.”

And, looking back, we may regard these times as good times compared with what follows.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.