Fetterman, Oz vie for Black voters in close Pennsylvania Senate race

- Share via

PHILADELPHIA — As Sheila Armstrong grew emotional in recounting how her brother and nephew were killed in Philadelphia, Dr. Mehmet Oz — sitting next to her inside a Black church, their chairs arranged a bit like his former daytime TV show set — placed a comforting hand on her shoulder.

Later, he gave a hug to Armstrong, who has been an employee of Oz’s campaign for Pennsylvania’s U.S. Senate seat, and said, “How do you cope?”

Two days later, on a stage four miles away, Oz’s Democratic rival, John Fetterman, stood with Lee and Dennis Horton and spoke of his efforts as lieutenant governor to free the two Black men from life sentences.

“Almost 30 years in prison, condemned to die in prison as innocent men, and I fought to make sure they come out to their families,” Fetterman told the crowd.

Black voters are at the center of an increasingly competitive battle in a race that could tilt control of the Senate, as Democrats try to harness outrage over the Supreme Court‘s abortion decision and Republicans tap the national playbook to focus on crime in cities.

They are perhaps the Democratic Party’s most loyal supporters. About nine in 10 Black voters nationally went for Joe Biden in 2020, according to AP VoteCast, an expansive survey of more than 110,000 voters nationwide. In Pennsylvania, the support was similar, at 94%.

Trump-backed Mehmet Oz faces daily trolling on social media; now his campaign is mocking Democrat John Fetterman over his stroke, as key Senate race heats up.

There’s no evidence of a looming mass defection to Republicans like Oz. But if he can peel off even a small share — or a critical mass of Black voters choose not to vote — it might prove consequential in a race that polls show as close.

In Philadelphia, where Black voters are the largest bloc in the swing state’s biggest Democratic bastion, some activists question Democrats’ outreach and fret about turnout.

Charles Ellison, the executive producer and host of Reality Check, a daily public affairs program on Philadelphia’s prominent Black-themed WURD radio, said Democrats lack a unified message tailored for the Black community and didn’t undertake a long-term investment in Black voter outreach.

“There’s just not this realization that’s occurring that Pennsylvania is a national battleground and Philadelphia is the cornerstone in that,” Ellison said. “And the only way you’re going to get Philadelphia and the only way you’re going to get Pennsylvania is through maximum Black voter turnout.”

Fetterman may benefit from this year’s governor’s race.

In it, Democrat Josh Shapiro’s campaign said it is investing $3 million in Black voter outreach while his opponent, Republican Doug Mastriano, has drawn criticism from members of his own party for focusing almost exclusively on his right-wing base.

Shapiro is also making regular visits to Black churches and businesses, has rolled out a platform to expand pathways to jobs and create wealth in Black communities, and endorsed a Black man, Austin Davis, for lieutenant governor.

In the Senate race, millions of dollars in Republican attack ads aired on TV in Philadelphia before Fetterman — who spent much of the summer off the campaign trail recovering from a stroke — held his first public political event there in late September.

For Oz, crime is a primary thrust. He has held two public safety-themed town halls in Black communities, suggesting that Democrats have failed to protect them from violence and drugs.

Republicans frequently point to gun violence in Philadelphia and have sought to undercut one of Fetterman’s avenues of appeal to Black voters: his efforts as lieutenant governor to free the over-incarcerated, rehabilitated or innocent. Republicans cast it as freeing dangerous criminals to roam the streets.

Call it the ‘I don’t know’ election in the fight for Congress. Republicans still have advantages, but Democrats appear energized in the post-Roe environment.

Fetterman and Democrats call that a lie and fearmongering that underestimates support among Black voters for giving second chances. And they say Black voters know they can trust Fetterman to support the things they care about, like voting rights legislation in Congress.

Plus, Oz is former President Trump’s endorsed candidate.

“I think most Black people would say he was one of the worst presidents for Black people in our lifetime,” said Sharif Street, the state Democratic Party chair and the first Black person to hold the position. “I don’t think a TV commercial can override what people know to already be true.”

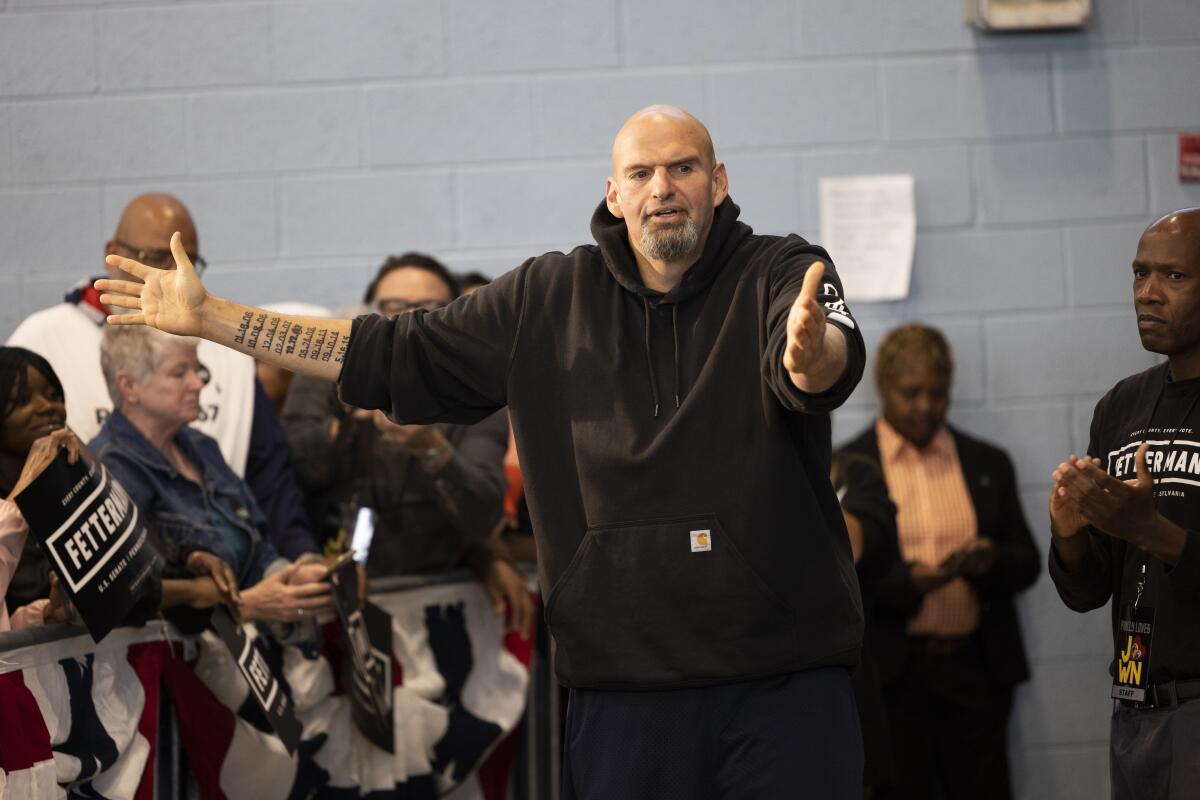

At Fetterman’s rally at a recreation center in northeast Philadelphia, at least a half-dozen Black supporters introduced Fetterman.

One of the speakers, the Rev. Mark Tyler, said Fetterman supports things that Black voters care about, such as bringing jobs to “America’s poorest big city,” ending environmental racism and supporting stronger funding for city schools. Fetterman also supports criminal justice reform and ending gun violence, Tyler said.

“He did it as a mayor in Braddock and understands what it is to have to sit and stand with grieving Black families after such a tragic incident,” Tyler said.

As Fetterman stood onstage with the Hortons — brothers who had their life sentences commuted after nearly 30 years in prison, and now work for Fetterman’s campaign — he took aim at Oz’s attacks for his work to free the men. Oz’s campaign has called the Hortons “convicted murderers” and Fetterman “the most pro-murderer candidate for the Senate in the entire country.”

In the November midterm election, California is one of the battlefields as Democrats and Republicans fight over control of Congress.

The Hortons were convicted of second-degree murder in a fatal shooting during a robbery in a Philadelphia bar — crimes they maintained they didn’t commit. Despite opposition from the victim’s brother, Gov. Tom Wolf freed the men in late 2020, noting they had served 27 years after turning down plea deals for five to 10 years.

“What does it say about a person’s character if they will fight to make sure innocent men will die in prison versus a man that will fight to make sure that they’re able to get back with their families?” Fetterman asked the crowd. “That’s the choice.”

Oz-allied groups have also aired TV ads reviving a 2013 incident in which Fetterman — as Braddock’s mayor — grabbed his shotgun and pursued a jogging Black man whom he suspected had been involved in gunfire nearby. No one was charged in the incident and Fetterman has said he didn’t know the man’s race before he confronted him.

“He didn’t even apologize and now he wants our vote?” says a Black woman speaking on camera in an ad by the Republican Jewish Coalition. “Not a chance.”

Oz’s town halls take a softer tone, where the heart surgeon-turned-TV talk show host says he is there to listen and find solutions to problems that Democrats have let fester.

“The best thing a doctor does is listen. You can’t fix a problem you don’t hear. So I’ve spent a career heeding that and trying to understand what people are trying to say because then you can really get to the answers,” Oz said. He’s also touted his work to raise money for scholarships for Black medical students.

Love Williams, a 25-year-old registered Democrat who came to Oz’s event at the invitation of a friend, said he wasn’t sure he’ll vote this fall after feeling like Biden has underdelivered for Black people.

Asked by Williams what he’d do to help his community, Oz said he’d push for more tax dollars for private schools and to open liquefied natural gas export stations in the city to bring wealth into the community.

Williams said afterward that he wasn’t sold on Oz — or Oz’s ideas, either.

The event, he said, came off as “just a political stop for one politician.”

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.