Election workers train for battle against conspiracy theories and misinformation before midterms

- Share via

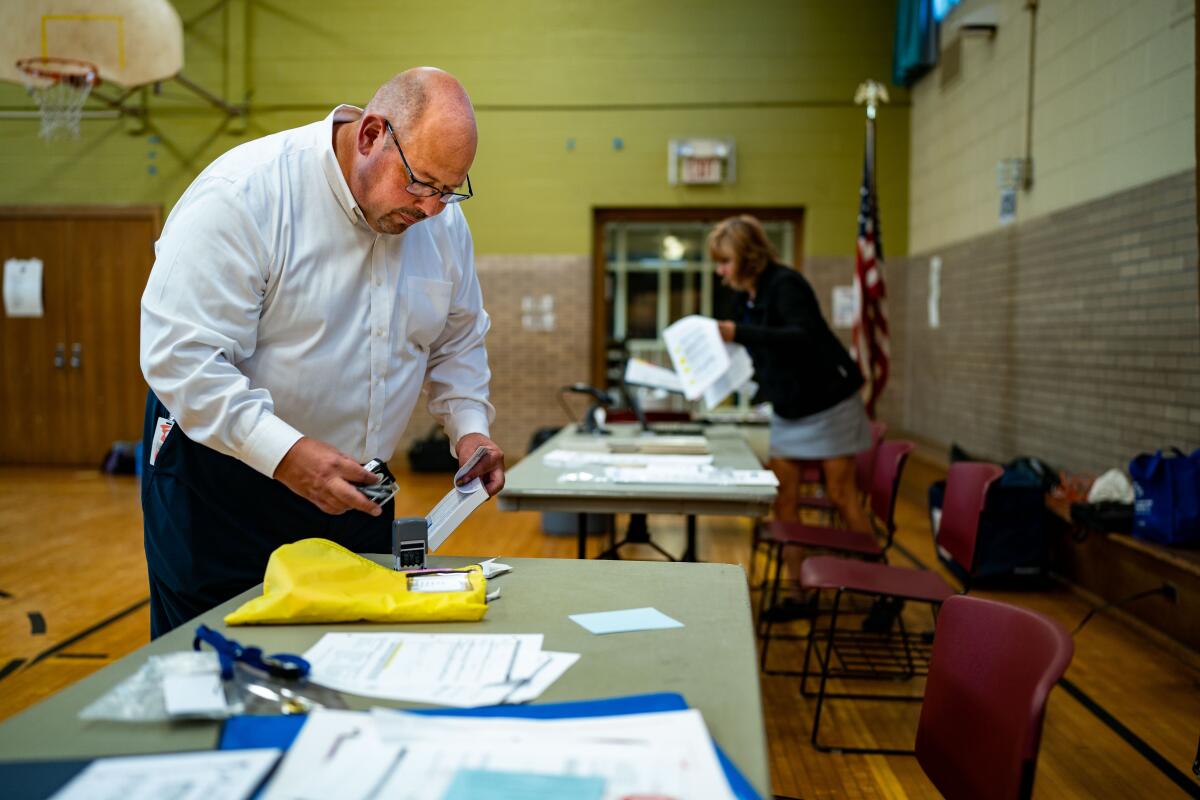

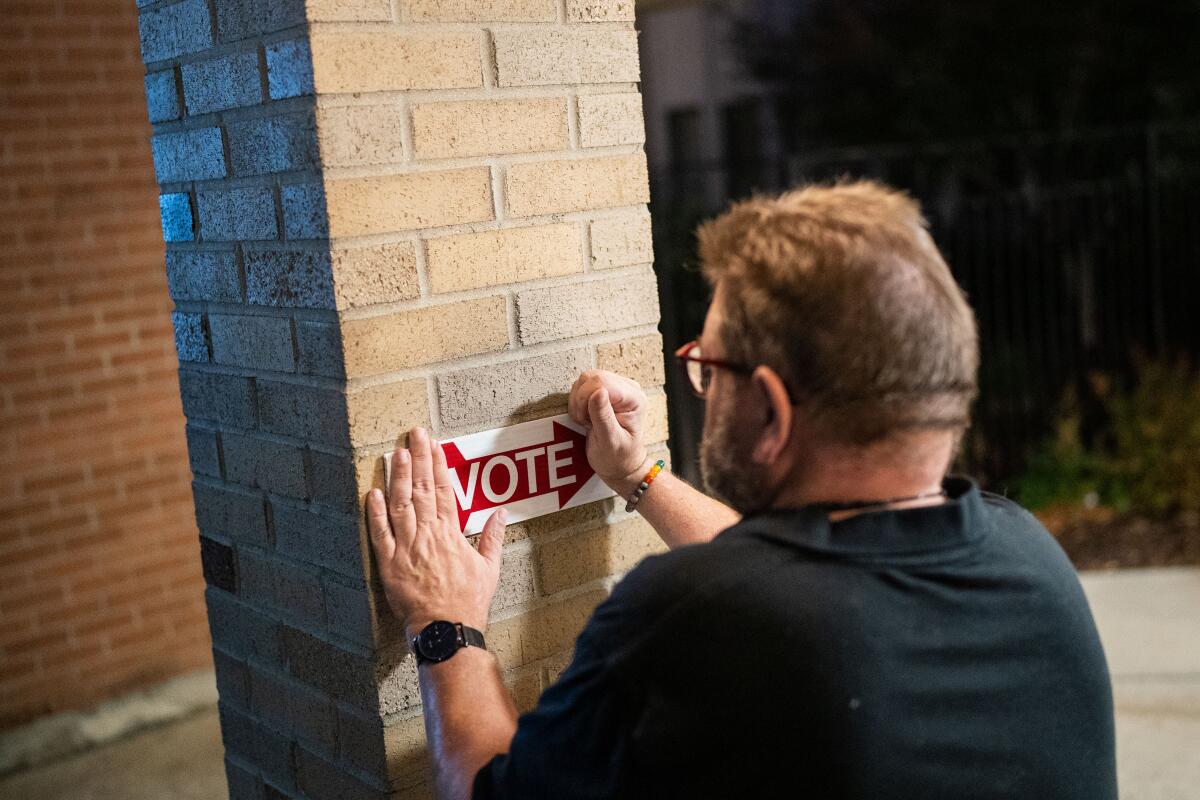

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — From his perch in an elementary school gym during last month’s Michigan primary, Grand Rapids City Clerk Joel Hondorp oversaw the electronic book of eligible voters, while first-time election workers Kimberly and Shayne Becher helped check people in and explain how to fill out ballots.

Kimberly, a 59-year-old counselor from Greenville, said she and her husband wanted to get involved “to learn how this all works,” since neither is convinced that the 2020 presidential election hadn’t been stolen.

“You just go to a Trump rally or go to a Biden rally, that will tell you … who won,” said Shayne, a 53-year-old carpenter.

Hondorp hopes that the Bechers and others trained by his office, with a successful election behind them, will change their minds about the process.

“Hopefully, they’re going to go back and talk to their friends and family … and say: ‘Hey, this is what we observed,’” Hondorp said.

Across the country, election clerks have spent the last two years waging an information and public relations battle to restore faith in elections. They’re doing more TV interviews, giving more office tours and retooling their social media presences. They’re keeping up with legislation to overhaul elections and conspiracy theories spreading online. And they’re redoubling their efforts to explain the exhaustive steps they take to prevent fraud and run secure elections.

But as the 2022 primaries showed, some of the key personnel involved — poll workers and poll challengers — still actively doubt the results of the 2020 presidential race, believing baseless allegations of fraud perpetuated by former President Trump and his allies.

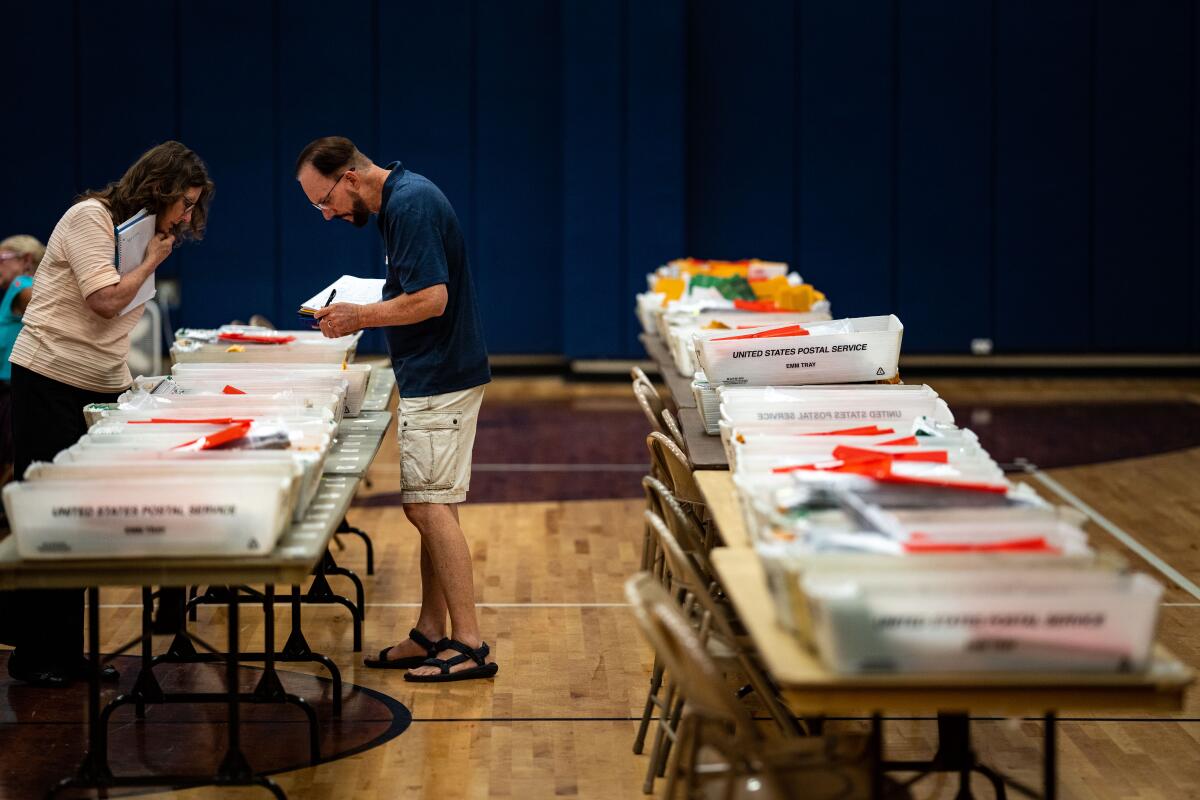

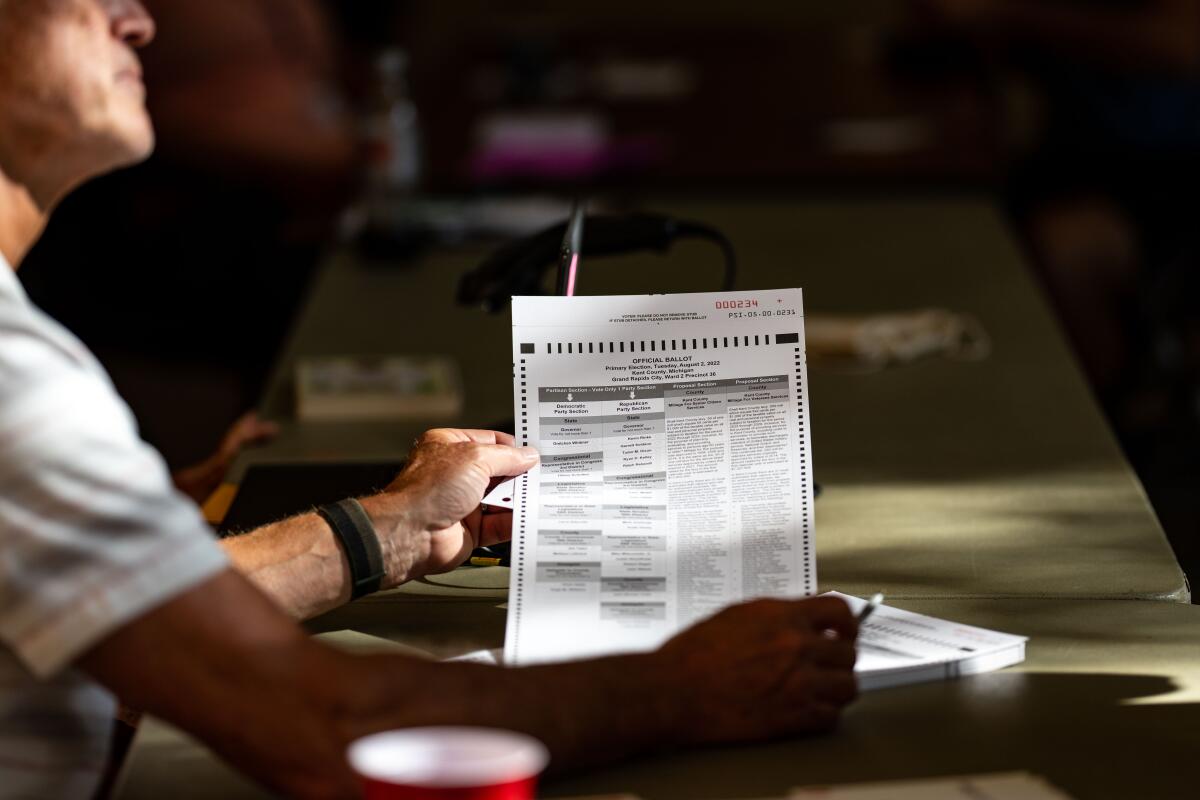

In Michigan, poll workers are hired and trained by local election clerks to help run voting precincts and count mail ballots. They’re affiliated with a political party and often work in bipartisan teams. Poll challengers, meanwhile, are trained by and registered with political parties or interest groups — including both conservative activist organizations and left-leaning voting rights groups — to observe election workers and flag potential misconduct or election law violations by poll workers. They have more rights than Michigan poll watchers, who can merely observe the electoral process.

Before the November midterms and the 2024 presidential election, concerns are growing that conspiracy-minded people in those positions could further corrode trust in the process by spreading misinformation or violating procedures. For example, Kristina Karamo, Michigan’s Republican nominee for secretary of state, rose to prominence in conservative circles after making baseless claims of voter fraud while serving as a poll challenger in Detroit in 2020. Trump has endorsed Karamo for the office, which as in other states has become increasingly visible and politicized since the 2020 election.

The Republican National Committee has continued to build up its recruitment of poll workers and challengers in states such as Michigan after being freed of a decades-long consent decree that barred it from such activities. The RNC has hired state directors and attorneys to work in 16 states — including California, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, Florida, Wisconsin and Michigan — with a goal of recruiting 5,000 poll workers in each state.

Last July, Vice President Kamala Harris announced that the Democratic National Committee would spend $25 million on its “I Will Vote” efforts, which includes recruiting poll challengers. While Republicans frame their recruitment efforts around the idea of “election integrity,” Democrats have called the work “voter protection” and sought to avoid the negative association behind terms such as poll challenger.

“Election Day Poll Challengers serve as our team’s eyes and ears on the ground at polling locations on Election Day,” according to the Michigan Democratic Party’s website. “Our Challengers do NOT challenge voters; rather, they advocate for voters.”

In Michigan, a coalition of county, state and national Republican groups led by the state GOP has spearheaded the effort to recruit thousands of poll workers in the state. One of those organizations is Stand Up Michigan, a conservative activist group that grew out of opposition to Michigan’s COVID-19 policies.

“We’ve got to basically let them know … that we are going to be monitoring and watching every step of the way, and we need to be a part of all the process,” Ron Armstrong, president of Stand Up Michigan, said during a June podcast interview with Cleta Mitchell, a lawyer who sought to help Trump overturn the results of the 2020 election.

In some cases, such groups have encouraged poll workers to break the rules. Before the August primary in Michigan, Wayne County GOP chairwoman Cheryl Costantino told poll workers to sneak in phones and pens to take notes on alleged fraud, according to a CNN report.

“They are actively trying to encourage people to not comply with their employers directions, and that is extraordinarily concerning,” said Barb Byrum, the clerk for Michigan’s Ingham County, home to the state capital of Lansing.

An election worker or challenger who subscribes to conspiracy theories could jeopardize the secrecy of ballots by bringing a phone into the absentee voter ballot counting board, or slow down the process, Byrum said.

“It’s designed to create havoc. And make no mistake about it, I believe that this is merely a trial run for 2024,” she said.

Local conservative groups, such as Michigan’s Election Integrity Force, have recruited and trained election challengers to observe the process across the state. The group’s website claims there was “a massive amount of evidence of rampant, systemic election fraud” in 2020 and notes that it is working to build “mass awareness on systemic election fraud” and drive forward “the process of decertification of fraudulent elections.”

The Election Integrity Force is also part of a lawsuit filed this month seeking to decertify the results of the 2020 election in Michigan and hold a new election, arguing without evidence that the voting machines used in the 2020 election weren’t certified.

In a training for challengers before the Aug. 2 primary, the organization recommended calling 911 and involving law enforcement to maintain a record of any issues, according to a recording of a Zoom meeting obtained by Politico.

Poll challengers also have become more aggressive in their approach to dealing with election officials and poll workers.

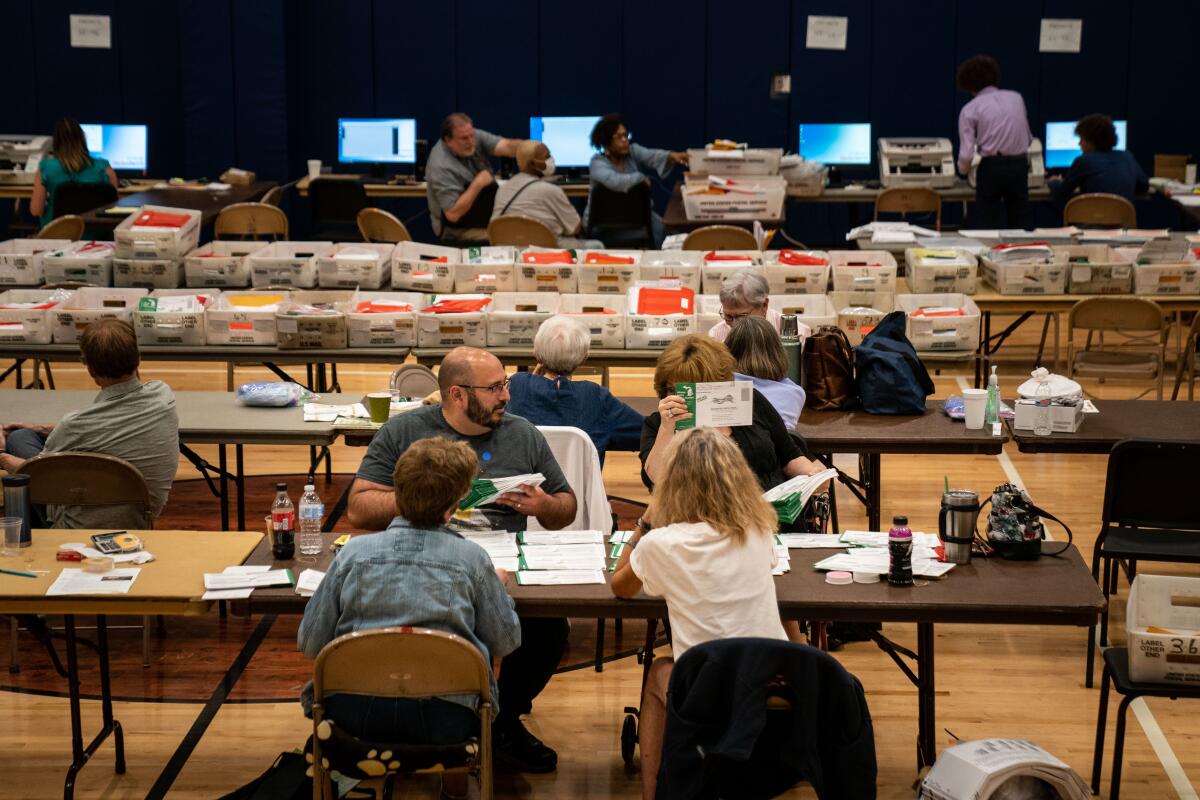

Nicholas and Harrison DeChant, 24-year-old twin brothers from Grand Rapids who volunteered to help count absentee ballots in the 2020 general election and the 2022 primary as Democrats, said they felt the increased scrutiny.

“The way that they interacted with the workers, we thought, was much closer than we had experienced in 2020,” Harrison said.

Half a dozen challengers peppered them with questions while they opened ballots. As they ran the ballots through vote tabulators it was “question after question after question,” they both said. There were queries about where the data go and what purpose a particular computer served. When one of them put a box on the ground because there wasn’t room on the table, a challenger asked why he was “hiding” ballots.

In spite of the distractions, the DeChants said, they were able to answer most questions or refer the poll challengers to a member of the clerk’s office.

Hondorp said he sensed that some people came into his office’s election worker training with preconceived notions, but his hope was that the two-hour session and hands-on experience dispelled some misconceptions about the process.

“Some of them are still not gonna believe it, because they just don’t trust the system, and there’s nothing that I can do,” he said. “I’ve done all I can do to give the information and provide it in the right context.”

Late into the afternoon on election day, the Bechers had no complaints. Shayne said “nothing fishy” seemed to be going on, while Kimberly said it was a good experience.

“We’ll definitely keep involved,” she said.

Mark Laws, a Republican poll worker who spent election day processing mail ballots at the absent voter counting board, also had a good experience.

“I don’t have any problem with everything that’s here,” said Laws, a 62-year-old semi-retired operations management professional. “My concern would be what happens before here and what happens after here.”

Hondorp said he doesn’t see challengers as an adversary. He noted that his background — a mix of political work for the Michigan Republican Party and decades of nonpartisan election work — has prepared him for the newly polarized landscape of election administration.

“If I did my training properly for my election workers and gave them good instructions on what the law was and what they’re supposed to do, it shouldn’t be an issue,” he said.

Still, he plans to focus more on the role that poll challengers play in future election worker trainings.

And on separating facts from social media rumors.

“My whole mindset now has changed from trying to just run an election in Grand Rapids, Mich., to now trying to explain how we do things in light of what’s happening in [other states],” he said.

That’s factored into how he trains election workers. During the 2020 election, a YouTube video of an Arizona woman claiming election officials tried to invalidate her vote by giving her a Sharpie to fill out her ballot went viral. Maricopa County election officials explained that the bleeding from the ink wouldn’t affect the ballot because the columns on the front and back are offset, but the rumor still spread to the rest of the country.

“That surprised us all,” Hondorp said. “All of a sudden we’re getting phone calls, blowing up our phones in Grand Rapids about what kind of pens we’re using.”

This year, as he was training poll workers for the primary, he anticipated the question and had an answer at the ready: They use PaperMate Flairs with felt tips.

Voter ID laws have also been in the spotlight. Under current Michigan law, voters who don’t have a photo ID are allowed to sign an affidavit attesting to their identity. About 0.2% of voters, 11,400 of nearly 5.6 million, filled out affidavits in the state’s 2020 general election.

A Republican-backed ballot initiative from Secure MI Vote would have made voter IDs mandatory. That initiative missed the deadline to be on the general election ballot. Promote the Vote’s Proposition 2, which will be on the ballot, would affirm the right to sign an affidavit.

Secure MI Vote’s initiative is part of a broader effort to make voter ID laws more restrictive across the country, including laws passed recently in states such as Missouri and New Hampshire to remove the option to fill out an affidavit. Instead voters must fill out provisional ballots that must go through extra steps to be counted.

For Hondorp and other election clerks, the challenge has been to clarify what the current law is, determine the status of ballot initiatives and address concerns about affidavits. In training sessions, he’s focused on clarifying that voter ID laws have not changed in the state, and that the current laws are sufficient to secure the vote.

“The advice I give — and what I give myself as well — is make sure you know your laws, rules, processes. And when you know them, be confident in them,” he said. “Don’t let someone sway you based on what they’ve heard … be firm in upholding what election law says.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.