Biden ups Ukraine aid as war with Russia enters new phase, but will it be enough?

- Share via

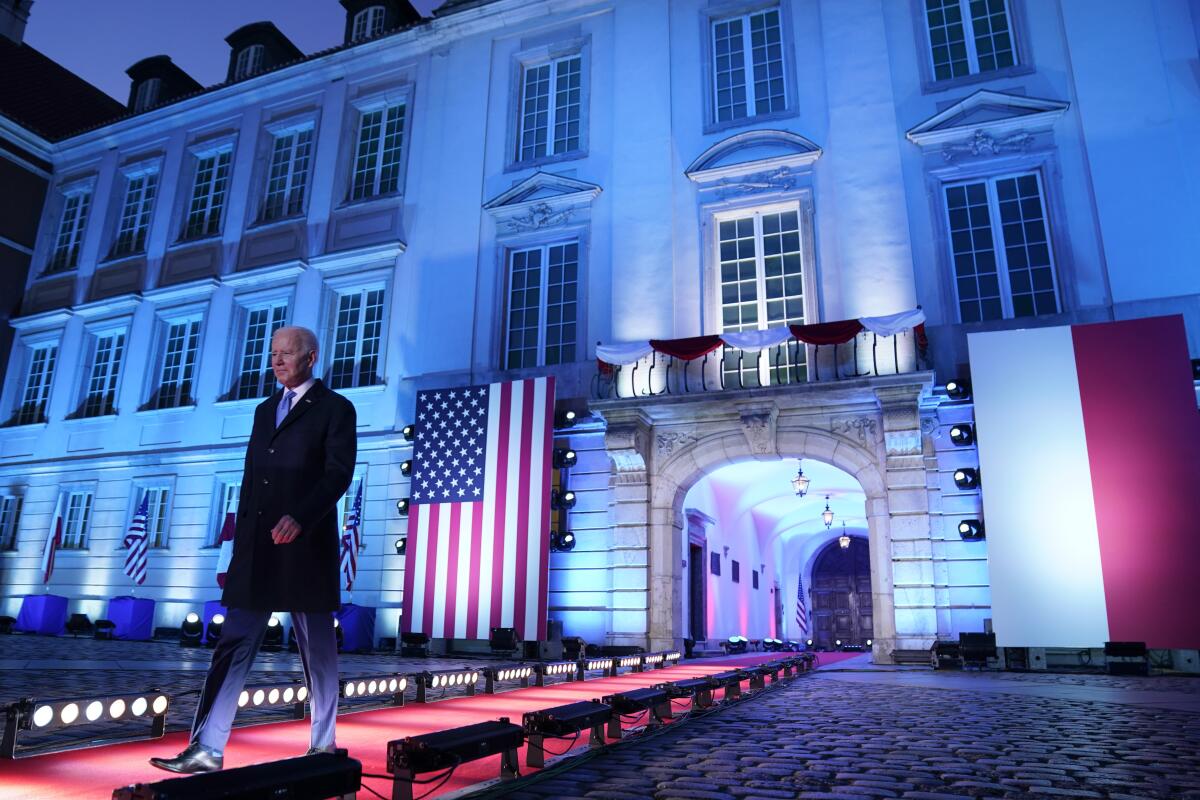

WASHINGTON — With a war many thought would be over in days bogging down into a protracted conflict, the U.S. and its NATO allies are recalibrating their response, scaling up defense aid for Ukraine as it digs in for a longer fight with Russian forces.

But even as President Biden has vowed not to let Russia win, it’s not at all clear an enhanced response will help Ukraine win the war or avoid a years-long conflict that is likely to strain the transatlantic alliance, cost billions in additional aid, further disrupt global economic markets and lead to more bloodshed on the front lines.

“It’s going to be a different kind of war, and there has to be a greater urgency,” said Eric Edelman, a former undersecretary of defense. “If Russia isn’t successful right away, Ukraine might still hold a strategic advantage in the long term. But that depends on how long they can absorb casualties and maintain a will to fight, and how long the West can keep this up.”

As part of Washington’s continuing efforts to bolster Ukraine’s war-fighting capabilities, Biden announced Tuesday a new tranche of $800 million in defense assistance for Kyiv. It includes advanced weapons and ammunition including artillery systems, armored personnel carriers and the transfer of more helicopters to help Ukraine blunt Moscow’s latest offensive in the eastern Donbas region and the besieged city of Mariupol.

The announcement, following an hour-long call between Biden and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, came as the White House is facing pressure to take stronger actions as the war stretches into its eighth week.

Although the latest aid package increases the U.S. commitment to what administration officials have conceded could be a years-long conflict, the White House remains wary of greater U.S. involvement that might change the trajectory and length of the war — even as Biden has called Russian President Vladimir Putin a “war criminal” and characterized the Russian campaign as “genocide.”

Such presidential rhetoric — which went beyond official White House policy — raises the stakes for U.S. and NATO involvement, according to Ivo Daalder, the president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

“The president needs to signal that we will do whatever it takes for Ukraine to succeed because you can’t call people out for war crimes, let alone genocide, and not do everything possible,” said Daalder, who served as U.S. ambassador to NATO in the Obama administration.

“The more ratcheted up the rhetoric,” he added, “the more incumbent it comes on us to actually fulfill what that means.”

Since Russia’s invasion in February, the White House has tried to strike a balance between backing Ukraine and avoiding direct and potentially escalatory engagement with a nuclear power that could turn a regional war into a global one. Biden has made clear he will not send American troops to Ukraine or establish a no-fly zone, steps officials say could bring the U.S. into conflict with Moscow. So far, the White House has focused on bolstering the NATO alliance, punishing the Kremlin with sanctions and supplying Ukrainians with weapons and intelligence.

The Department of Defense said last week it had delivered thousands of antiarmor and antiaircraft systems, including Stinger and Javelin missiles, laser-guided rocket systems and more than 50 million rounds of ammunition as part of two packages of security assistance the president approved in March.

The latest package expands on the $1.7 billion in security assistance the U.S. has provided Ukraine since Russia launched its invasion on Feb. 24 and the $2.4 billion in aid since Biden took office.

It’s unclear if, or how, the West might send more powerful weapons, such as U.S. military jets and Apache helicopters, that it’s thus far avoided.

The Biden administration has resisted such transfers for logistical reasons — the U.S. would not only have to train Ukraine’s military how to operate, say, an F-16, but also establish supply lines and infrastructure to maintain such equipment. U.S. officials believe that would take too long to be helpful.

Russia’s flagship in the Black Sea has suffered ‘significant damage’ as Ukraine said it attacked the vessel with a shore-to-ship missile.

Ukrainians, meanwhile, are pleading for Washington to ship them advanced arms as they are urging U.S. officials to consider the geopolitical realities of a protracted fight.

“Russia will be here forever as a neighbor of Ukraine,” said Daria Kaleniuk, co-founder of Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Action Center. “We need to get prepared for a sustainable solution with advanced NATO-style weapons.”

Kaleniuk and a delegation of Ukrainian civil society advocates and former government officials met with dozens of U.S. lawmakers last week, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and officials from the State Department and White House.

“There’s still some fear about being too provocative to Russia. There’s fear of nuclear weapons,” she said following her White House meeting. “But deterrence works both ways and Putin uses deterrence.”

Experts have applauded the White House’s efforts to assist Ukraine but say the Biden administration and its allies took too long to act, complicating Ukraine’s ability to fend off the invasion.

“They were always slow and way too cautious about actually implementing it,” said John Herbst, a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine. “They repeatedly refused to take steps in fear of provoking Putin.”

Pressed about whether aid is arriving too late as Russia shifts its focus to an eastern offensive, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said on Tuesday that “we are going to move this as fast as we can,” arguing the assistance the U.S. has already sent is playing a role in Ukraine’s defense.

“We’re aware of the clock and we know time is not our friend,” Kirby told reporters.

The big battle for eastern Ukraine is coming, but in the south, Ukrainian soldiers have pushed back the front lines of Russian forces.

Daalder, the former U.S. ambassador to NATO, said the administration’s challenge on timing is in whether it can quickly acquire the equipment and weapons that Ukrainians are trained to use. Much of it was manufactured by Russia or in countries that were once part of the Soviet Union (Ukraine was a Soviet republic).

“The delay is not really what is the U.S. providing,” Daadler said. “It’s: How do you get the equipment that’s among the former Warsaw Pact countries rapidly to Ukraine and what do you do to backfill those capabilities in order to make sure that NATO is still defended?”

Biden last week announced the U.S. repositioned a Patriot missile system to Slovakia, which borders Ukraine, to backfill its transfer of a Soviet-era S-300 defense system to Kyiv to fend off airstrikes. But in March the administration rejected a three-way deal to transfer MiG 29 fighter jets from Poland, a NATO member and regarded as a former Soviet satellite, to Ukraine after deeming it too “high risk.”

Despite such fissures, NATO has remained mostly unified even if members’ interests aren’t always aligned. Major gulfs could emerge as the conflict drags on, however.

Germany, Europe’s largest economy, has waffled on cutting off imports of Russian oil and gas due to recession fears; the country’s coalition government is split on whether to send German-made tanks to Kyiv.

If far-right candidate and Putin ally Marine Le Pen ousts French President Emmanuel Macron in a run-off election later this month, it would immediately puncture NATO’s newfound solidarity. That unity may deepen this summer if Finland and Sweden end decades of neutrality and join the alliance, as is expected. But even if bonds among democratic leaders hold, the threat of Putin in Ukraine and to the rest of Europe could only grow.

Constanze Stelzenmüller, a Germany expert at Washington’s Brookings Institution, said NATO’s response to Putin in Ukraine has been “the most considered, forceful and effective Western response to any crisis that I’ve seen. But events on the ground may still show that what we’re doing is not enough, because Putin is clearly determined to test us. And we may have to change our definition of what we can do.”

The U.S. almost certainly will have to play a big role in providing security guarantees and aid to a postwar Ukraine.

As the grisly nature of past Russian atrocities is uncovered and as Ukrainian losses mount during what’s expected to be heavy fighting in the Donbas, the political pressure for the West to do more is likely to grow. But the cold, hard reality, many experts believe, is that the war quickly becomes a frozen conflict.

“Putin is not going to capitulate,” said Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group, a global risk assessment firm. “The reason why the administration believes this is likely to be a stalemate is that, in some ways, that is the least worst plausible outcome that we are headed towards.”

Dan Baer, former U.S. ambassador to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe during the Obama administration, said that “the scenarios by which it ends tomorrow are not necessarily ones that are satisfactory for the long-term stability of the region or the world.”

“If it’s going to be protracted, what you want is a slower and lower burn so there’s less human cost. Because faster could mean Ukrainian defeat,” he said. “Of course I don’t want it to drag out, but if you take all of the possibilities for a fast [resolution], there are fewer of them that look good for the Ukrainians.”

“This is a Russian novel and we’re in Chapter 3, and the bad news is that there are 57 chapters,” he added.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.