Half its original size, Biden’s big domestic policy plan is in a race to the finish

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Half its original size, President Biden’s big domestic policy plan is being pulled apart and reconfigured as Democrats edge closer to satisfying their most reluctant colleagues and finishing what’s now about a $1.75-trillion package.

How to pay for it all remained deeply in flux Tuesday, with a proposed billionaires’ tax running into criticism as cumbersome or worse. The uncertain funding is forcing difficult reductions, if not the outright elimination, of several priorities — including paid family leave, child care, and dental, vision and hearing aid benefits for seniors.

The once hefty climate change strategies are losing some punch, too, shifting away from punitive measures against polluters in favor of incentives to reward clean energy.

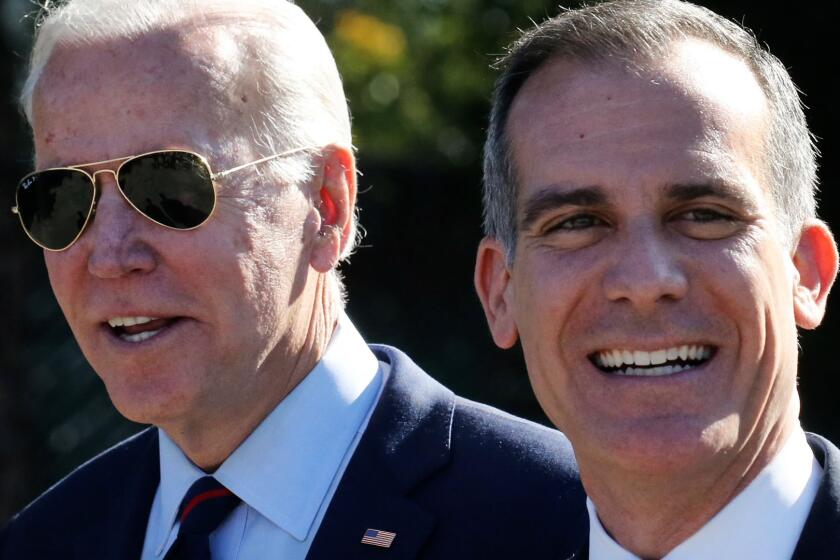

With pressure mounting, Biden met Tuesday evening with two holdout Democratic centrists — Sens. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, according to a person who requested anonymity to discuss the private meeting. The president is pushing for an agreement before he departs for global summits later this week.

All told, Biden’s package remains a substantial undertaking — and could still top $2 trillion in perhaps the largest effort of its kind from Congress in decades. But it’s far slimmer than the president and his party first envisioned.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) told lawmakers they were on the verge of “something major, transformative, historic and bigger than anything else” ever attempted in Congress, according to another person, who requested anonymity to share remarks Pelosi had made to her caucus in private.

Means-testing social programs can doom them to failure. Here’s why.

“We know that we are close,” said Rep. Joyce Beatty (D-Ohio), chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, after a meeting with Biden at the White House. “And let me be explicitly clear: Our footprints and fingerprints are on this.”

However, vast differences remain among Democrats over the basic contours of the sweeping proposal and the tax revenue to pay for it.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Biden still hoped to have a deal in hand this week to show foreign leaders the U.S. government is performing effectively on climate change and other major issues. But she acknowledged that might not happen, which would force the president to keep working on the package from afar.

She warned about the risk of failure without a compromise.

“The alternative to what is being negotiated is not the original package,” she said. “It is nothing.”

More lawmakers journeyed to the White House for negotiations on Tuesday and emerged upbeat that the end product would be substantial, despite the changes and reductions being forced on them by Manchin and Sinema.

Because of differences in the way low-income housing is addressed state by state, proposed cuts have set off a West Coast-East Coast tug of war.

Together the two centrists have packed a one-two punch — Manchin forcing supporters to pare back healthcare, child care and other spending, and Sinema causing Democrats to reconsider their plans to reverse the Trump-era tax cuts on corporations and the wealthy.

Resolving the revenue side is key as Biden insists that all of the new spending will be fully paid for and not piled onto the national debt. He vows any new taxes will hit only the wealthy — those earning more than $400,000 a year, or $450,000 for couples — and says corporations must quit skipping out on taxes and start paying their “fair share.”

But the White House had to rethink its tax strategy after Sinema objected to her party’s initial proposal to raise tax rates on corporations and the wealthy. With a Senate divided 50-50, Biden has no votes to spare in his party.

Instead, to win over Sinema and others, Democrats were preparing to unveil a new plan for taxing the assets of billionaires. And on Tuesday they unveiled a proposal to require corporations with more than $1 billion in income to pay a 15% minimum tax, which Sinema supported.

“Here’s the heart of it: Americans read over the last few months that billionaires were paying little or no taxes for years on end,” said Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), who is leading the effort as chair of the Senate Finance Committee.

Under Wyden’s emerging plan, a billionaires’ tax would hit the wealthiest Americans, fewer than 1,000 people total. It would require those with assets of more than $1 billion, or three years of consecutive income of $100 million, to pay taxes on the gains of stocks and other tradeable assets, rather than waiting until holdings are sold.

President Biden’s proposals for new taxes on billionaires and companies to help fund his domestic agenda has the apparent backing of Sen. Joe Manchin but has been criticized by other lawmakers.

A similar billionaire’s tax would be applied to nontradeable assets, including real estate, but it would be deferred, with the tax not assessed until the asset was sold.

The overall billionaires’ tax rate was not set, but it was expected to be at least the capital gains rate of 20%. Democrats have said the tax could raise $200 billion in revenue to help fund Biden’s package over 10 years.

Republicans deride the billionaires’ tax, and some have suggested it would face a legal challenge.

Key Democrats were also raising concerns about the tax, saying the idea of simply undoing the 2017 tax cuts by hiking top rates was more straightforward and transparent.

Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), chair of the Ways and Means Committee, said, “Our plan looks better every day.”

Under the bill approved by Neal’s panel, the top individual income tax rate would rise from 37% to 39.6% on those earning more than $400,000, or $450,000 for couples. The corporate rate would increase from 21% to 26.5%. The bill also proposes a 3% surtax on the wealthiest Americans with adjusted income beyond $5 million a year.

The $2.8-trillion U.S. budget deficit for 2021 is an improvement from the record high of $3.1 trillion in 2020.

Manchin, who is less concerned about the new taxes, is forcing his party to reconsider the expansion of healthcare, child care and climate change programs he views as costly or unnecessary.

Still being debated: plans to expand Medicare coverage with dental, vision and hearing aid benefits for seniors; child-care assistance; free prekindergarten; a new program with four weeks of paid family leave; and a more limited plan than envisioned to lower prescription drug costs.

On climate change, Manchin, a coal state lawmaker, rejected Biden’s earlier clean energy strategy as too punitive on producers that rely on fossil fuels. The White House has floated an idea in its place to beef up grants and loans to create incentives for clean energy sources.

Manchin’s resistance may scuttle one other tax proposal: a plan to give the Internal Revenue Service more resources to go after tax scofflaws. He said he told Biden during their weekend meeting at the president’s home in Delaware that that plan was “messed up” and would allow the government to monitor bank accounts.

Democrats are hoping to reach an agreement by week’s end, paving the way for a House vote on a related $1-trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill before routine transportation funds expire Sunday. The roads-and-bridges bill stalled when progressive lawmakers refused to support it until deliberations on Biden’s social and climate package were complete.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.