Vaccines and Trump: Will Newsom’s formula for beating the recall work for Democrats in 2022?

- Share via

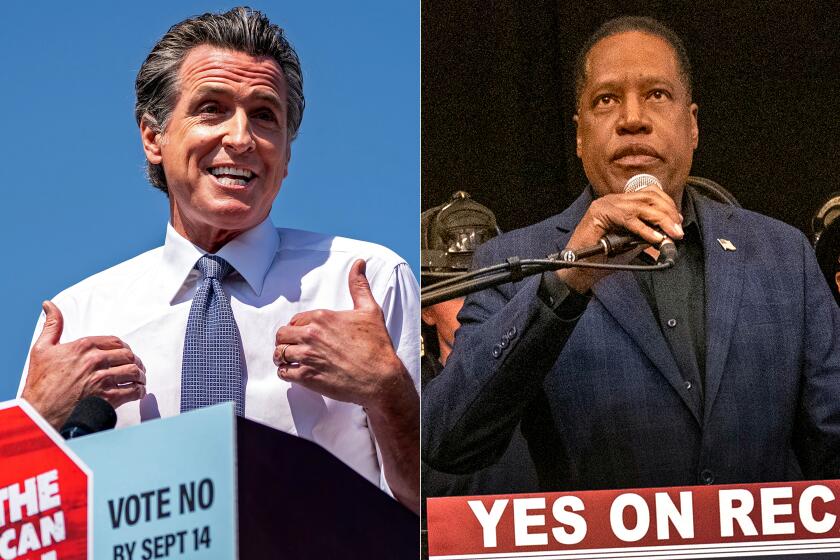

Gov. Gavin Newsom decisively fended off a recall with a two-pronged strategy: nonstop GOP bashing and an unapologetic embrace of vaccine mandates. Now, the architects of his win say Democrats across the country should follow suit in next year’s midterm election.

“Step 1: Name the villains,” said Sean Clegg, a top advisor to the campaign. “Step 2: Describe the stakes” — which Newsom portrayed as a life-or-death choice on ending the pandemic.

For national Democrats facing an uphill battle to keep control of Congress in 2022, those two steps behind Newsom’s overwhelming victory on Tuesday may offer a road map for success — the former rousing otherwise disengaged Democrats and the latter making inroads with independents and even some Republicans.

But prevailing in indigo-blue California is one thing, while eking out wins in swing states and congressional districts is quite another.

“Newsom had plenty of room for error, considering [Joe] Biden won by 29 points [in California] in 2020,” said Nathan Gonzales, editor of Inside Elections, which offers nonpartisan campaign analysis.

Democrats in purple states “essentially have no room for error,” he said. “They can’t afford any slippage in Democratic turnout, they can’t lose any independent voters, and they can’t afford Republican turnout to surge.”

Here’s what we know after the polls closed about the attempt to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom.

There are myriad reasons that Tuesday’s election cannot neatly be seen as a test run for 2022 nationally. A special election governed by California’s quirky recall rules is inherently different than conventional head-to-head matchups during the heat of a national election season. And California’s overwhelming Democratic tilt meant the math was always in Newsom’s favor.

Still, Newsom’s campaign realized early that surplus would do little good if those voters didn’t show up. According to internal campaign polls obtained by The Times, 70% of Republicans in the state had heard quite a bit about the recall in February, when proponents were gathering signatures to get it on the ballot, while just 36% of Democrats said the same.

The asymmetry was especially pronounced in this election off-year; the campaign’s focus groups found that Democrats in particular were eager to disconnect from political news. That dynamic threatens to carry over into the midterm next year, when the party out of power typically makes gains.

The question facing Democrats is, “how do you wake up that base to not fall to historical trends of midterm low performance and turnout?” said Juan Rodriguez, Newsom’s campaign manager. “That is where we could’ve been” in the recall election.

The Newsom campaign’s response was to frame the election as a right-wing power grab, using former President Trump as a bogeyman. The campaign homed in on replacement candidate Larry Elder, the talk radio host, as a stand-in for Trumpism, which amped up Democratic engagement. By the end of summer, Democrats were nearly on par with Republicans in awareness of the recall, according to Newsom’s polls, and the election was presented as a choice, not a referendum on the governor’s performance.

Larry Elder shook up the recall campaign. What will the conservative talk radio host do next?

“When it’s a Democrat versus a Republican, and the Republican is a Republican in the Trump mold ... then you’re looking at numbers that are more like 60-40 instead of 52-48,” said David Binder, a pollster who worked on Newsom’s campaign.

Elder, a first-time candidate with a tendency for provocation, may have been a blessing for Newsom, but the campaign says it wasn’t simply a one-time lucky break.

“The Larry Elder types are going to be on the ballot in other places,” Rodriguez said.

The tactic — using negative campaigning about your opponent to juice turnout among your base — is “a powerful component of our elections,” Gonzales said.

“Democrats have been searching for things to rally against,” he added. “The governor and his team found what they needed to make sure Democrats were sufficiently angry in order to turn out in a weirdly timed election.”

But a strategy that relies on fueling Democrats’ most reliable voters is far more straightforward in a blue state than in most competitive House and Senate races, said Meredith Kelly, a former spokesperson for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

Given the number of Democrats in California, “if you just get them excited enough or concerned enough to vote, you win,” she said. “In swing districts, there just aren’t enough Democrats to win by only turning them out, so everything becomes more nuanced and less partisan. “

Matt Gorman, a veteran GOP political strategist who worked for the National Republican Congressional Committee and the presidential campaigns of Jeb Bush and Mitt Romney, said Democrats risked learning the wrong lessons from Newsom’s win.

California voters overwhelmingly rejected the attempt to remove Gov. Gavin Newsom before the end of his term.

“Gavin has the luxury of going around and saying, ‘Republican, Republican, Republican,’ and having the state revert to the natural mean, in a heavily Democratic state,” Gorman said. “If Democrats try to do that in places like some of the seats in Orange County ... or in places across the country with suburban districts like Pennsylvania, that’s a very different thing. You’re not going to get that same visceral reaction you get statewide in California.”

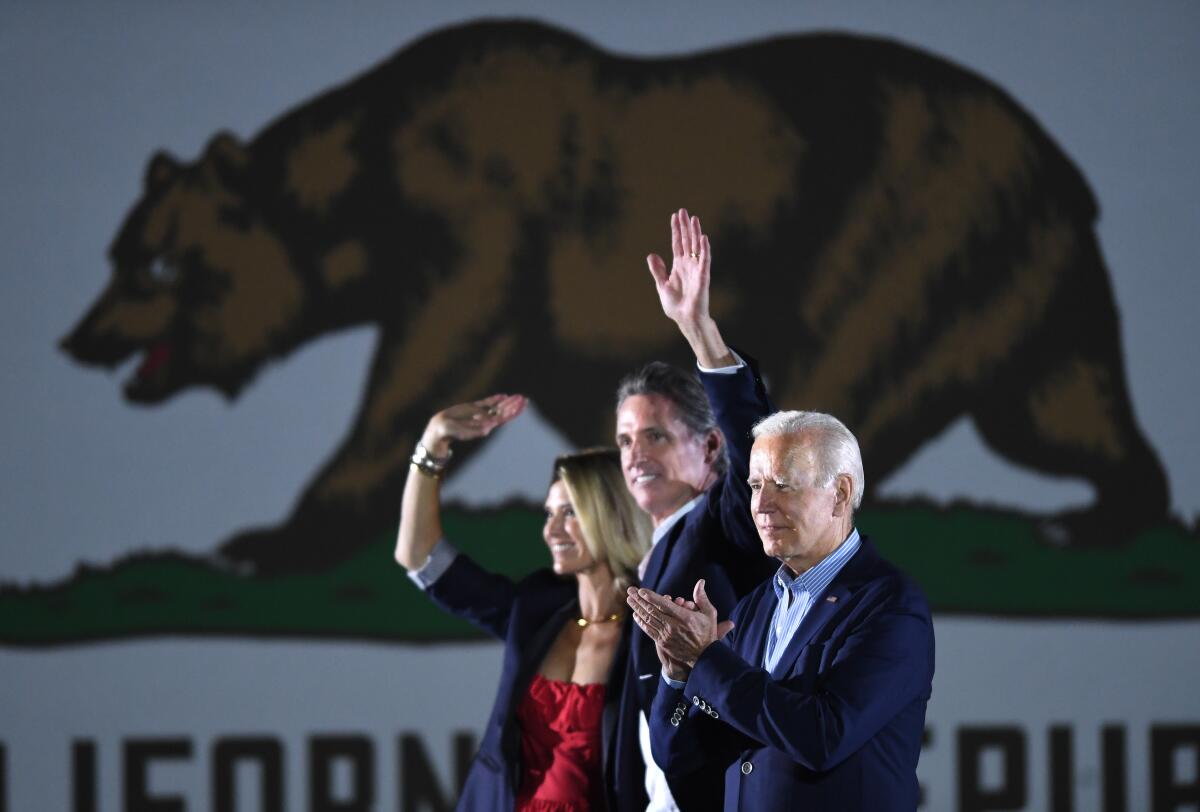

Some national Democrats, including those close to President Biden, have signaled they’d prefer to focus on the party’s accomplishments next year, putting less focus on Republicans and especially Trump. But in gubernatorial races this year — the recall election in California and contests in Virginia and New Jersey — Trump has been a central figure.

In Virginia, Democratic gubernatorial contender Terry McAuliffe has been ceaselessly linking Glenn Youngkin, his Republican opponent, to Trump and the GOP-backed Texas abortion ban.

“After four years of being awake and paying hyper-attention because a madman was in the White House, a lot of Democrats now have sort of burnt out. The challenge for our party is that it is harder now to see the threat because we have a competent, experienced person as president,” said Fred Yang, a Democratic pollster working with McAuliffe. “Midterm elections are about getting out the base. Donald Trump and the Republican Party are still strong motivators for Democrats.”

On Tuesday, the California voters most active leaned toward recalling Newsom, but that was just part of the overall picture.

While the Newsom team had from the outset trained its focus on the conservative opposition, the governor’s closing message — an appeal based on his management of the pandemic — was not in the plan. Until the Delta variant emerged.

The public frustration over new coronavirus concerns offered Newsom opportunity. His campaign polling showed an appetite for vaccine requirements to hasten the end of the pandemic. Of the five different proposals in campaign surveys — including requiring vaccines for teachers and allowing businesses to impose vaccine verification for customers — all got at least 60% approval. Recent national polls from Morning Consult and Axios/Ipsos found similar levels of support for mandates.

Ken Spain, a GOP strategist and former spokesman for the National Republican Congressional Committee, acknowledged that Newsom’s stance may translate well for Democrats throughout the nation next year.

“Voters appear to like the vaccine mandates,” Spain said. Getting more aggressive on anti-COVID policies “helps Democrats close the gap to some degree on an issue that is cutting against them as COVID cases rise and the economic disruption continues.”

It is impossible to predict what the COVID-19 pandemic will look like next year, or whether the issue will remain top of mind for voters.

Binder, the Newsom campaign pollster, said that emphasizing the issue could still pay dividends, helping Democrats paint Republicans as extreme in their opposition to vaccine mandates, and combating the GOP’s relentless claims that Democrats are “socialists” or that they want to “defund the police.”

“The Democratic Party has had branding problems,” Binder said. “The thing that is different now with COVID — and it’s still applicable even if COVID is gone next year — is that Republicans have their own branding problem on par or worse than Democrats.”

The messaging matters beyond the Democratic base. Newsom’s campaign polling found that independent voters, who skew left in California, opposed the recall by 17 points after being presented his stance on mandates in contrast with his opponents’ positions.

Voters’ inoculation status has become a new indicator for how they are likely to vote. Across all parties, vaccinated voters were more likely to oppose the recall than their unvaccinated counterparts; 15% of vaccinated Republicans, for example, were against the recall, compared with 1% of unvaccinated Republicans, according to campaign surveys.

While Newsom’s path to victory may offer some guidance for his party in the upcoming campaign season, it has not upended the fundamental political landscape.

“The Democratic majorities in the House and the Senate were vulnerable before the election and are still vulnerable after the election,” Gonzales said. “Republicans can have a very good election in 2022 without winning states or districts that are anywhere near as Democratic as California.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.