- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Some of the world’s most vulnerable people arrive at the U.S.-Mexico border every day.

Men and women fleeing violence in Central America, political strife in Haiti and Venezuela. Boys and girls sent alone by their families, in the hope that America will offer them better lives.

They are beckoned by the image of the United States as a welcoming and merciful nation. But a disturbing increase in racist and xenophobic attacks targeting Americans with Asian and Pacific Island backgrounds makes it brutally obvious that my country doesn’t always live up to its promise of acceptance.

Can a society that treats some of its own citizens of color as not fully American take responsibility for those who have left everything behind to become one of us?

Many in San Diego who welcome President Biden’s more sympathetic tone cautiously say yes. But as a Black descendant of enslaved Africans, I have reason to doubt.

It takes effort to see the best in America when the border comes into view as I drive a dusty road that runs along the southern edge of San Diego.

The most distinguishing feature is an imposing double layer of fencing, fortified with coils of razor wire, that climbs over hills, plunges down ravines and runs directly into the crashing waves of the Pacific.

When San Diego native Pedro Rios describes what this border represents for him, it dawns on me why I identify so strongly with the migrants gathered on the other side, even though my experience bears little outward resemblance to theirs.

“The border fence and all the infrastructure around it, like the concertina wire and the Border Patrol agents — these are all monuments to hatred,” says Rios, a specialist on U.S.-Mexico border issues at the American Friends Service Committee.

“And in the case of the Trump presidency, we can say the border was a monument to white supremacy that intended to define who belongs and who doesn’t, who merits entry into the United States and who doesn’t.”

It hurts to look out at this border and admit to myself that I, too, sometimes feel as if I’m standing on the outside of the U.S. looking in — an inconvenient guest in a nation created to advantage its white majority.

Rios, 48, says the border has caused suffering in his own family.

His paternal grandparents, who lived in Los Angeles, were both born in the United States. In the 1930s, they were among the hundreds of thousands of citizens and noncitizens of Mexican descent who were rounded up and forcibly removed from this country under the discriminatory Mexican Repatriation program.

As a Black man in America, I’ve always struggled to embrace a country that promotes the ideals of justice and equality but never fully owns up to its dark history of bigotry, inequality and injustice.

Now, more than any time in recent history, the nation seems divided over this enduring contradiction as we confront the distance between aspiration and reality. Join me as I explore the things that bind us, make sense of the things that tear us apart and search for signs of healing. This is one in a series we’re calling “My Country.”

Rios recalls what his grandmother, who eventually resettled in San Diego, told him about the experience — how her heart broke when the nation of her birth turned its back on her.

The current increase in migrants at the border forces Americans to wrestle with the uncomfortable question of who stays and who goes once again. The crisis has led to wrenching scenes of a mass deportation farther east in Texas and images of migrants crowded into makeshift holding facilities. With arrivals by minors reaching all-time highs in California, temporary shelters have been set up in San Diego as well as in Long Beach and Pomona.

This is hardly the outcome Biden planned for when he set about reversing the racist immigration policies of a predecessor who falsely claimed that migrant caravans from Central America were intent on invading the U.S.

Puerto Rican Kemuel Delgado hates having ‘one foot in and one foot out’ of America. But race wasn’t on his mind when he began pushing for statehood.

But Lori Riis, who operates a horse training facility with her husband within sight of the border, sees in Biden’s immigration stance the underlying decency that I’m searching for and that she believes America still possesses.

“It’s all geography,” Riis says as she takes in Mexico in the distance.

“If I’m blessed to be born on this side and someone else was born on the other side, I realize we can’t take them all in, but they’re human beings.”

::

It’s easy to feel lulled at first by the seemingly peaceful atmosphere of the border neighborhood that spreads out around Riis’ ranch along Hollister Street, about 20 minutes south of downtown San Diego. Birds chirp in the surrounding ranches and marshes. Horses carrying Mexican American cowboys known as charros clip-clop along a network of park trails. At a sprawling community garden, many plots have been decorated with lawn furniture and American flags.

The tranquility is fleeting, though.

Agents from U.S. Customs and Border Protection in white pickups, patrol wagons and four-wheelers pass by every couple of minutes.

“There goes another one,” Riis says one afternoon while riding her horse Stitch in a dirt arena at the 20-acre Rancho Los Amigos. An agent in an off-road vehicle rumbles past her property.

Riis says she used to frequently spot families who’d slipped across from Mexico wandering along the road before being apprehended by border agents, but the sightings slowed after Trump won the presidency in 2016 in part because of his vow to “build the wall.”

The 60-year-old lifelong Republican was turned off by Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and voted for Biden last year.

“We’re not bothered by the people crossing,” Riis says. “We never have to deal with any issues because of it.”

“Hopefully we’re going to see more compassion” toward migrants in the Biden era, she says. “We should be the land of opportunity.”

As I continue my drive, I think of the migrants I’ve seen in Mexico in years past: Men and women cried as they spoke of wanting to raise their children without the threat of gang violence. One woman had abandoned her hometown in Guatemala after being shot at by gunmen and receiving death threats for being transgender.

Churches and volunteers are coordinating the response in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, epicenter of an influx of migrants and unaccompanied children.

“Not only is it a physical journey; it’s an emotional journey,” says Michael Hopkins, executive director of Jewish Family Service, one of the local nonprofits that help migrants who’ve crossed the border.

“Beginning to let your guard down, to believe in people again — that does take time for many.”

America’s understaffed and overloaded refugee system presents its own problems even for migrants who legally enter the U.S., especially for those who lack lawyers or fluency in English.

“It’s setting people up to fail — indeed it already has failed many asylum seekers,” says immigration attorney Carmen Chavez, executive director of Casa Cornelia Law Center, a nonprofit agency that offers free legal services to asylum seekers.

Biden recently ended the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” program, which forced those seeking U.S. asylum to wait across the border or sneak in with the help of smugglers.

The danger of crossing illegally was highlighted in March. Thirteen migrants died when the SUV they were crammed into collided with a semi truck two hours to the east in Imperial County after passing through a hole in the border fence.

Tragedy struck again in early May when an overloaded boat crashed off San Diego in a suspected human smuggling attempt, killing at least three people and injuring dozens.

“These are very vulnerable people,” Chavez says. “It calls upon us as Americans to make sure this is a just process.”

::

On the day the Remain in Mexico policy ends, I exit a customs building onto a small plaza in downtown Tijuana, where I’m greeted by confusion and fear.

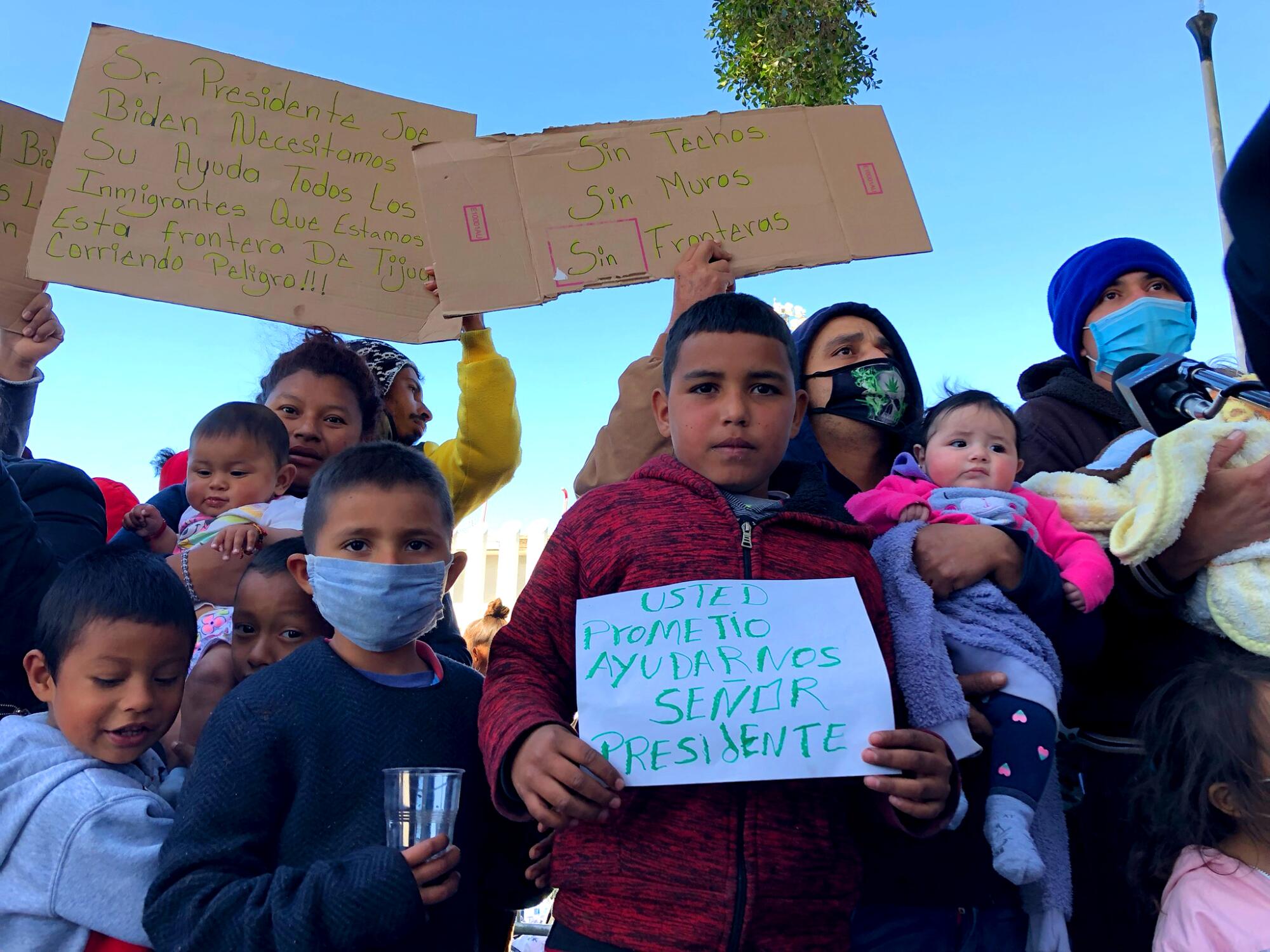

Hundreds of masked migrants from Central America and Haiti, some cradling babies, have gathered to see whether Biden’s empathetic tone on immigration means they’ll soon get to plead for asylum and live in the U.S. while their cases proceed.

A Honduran boy holds a cardboard sign with a handwritten plea: “You promised to help us, Mr. President,” it reads in Spanish.

I don’t have the heart to tell him the truth. Hondurans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Mexicans, despite filing the most asylum applications in recent years, have had the lowest success rates among all nationalities, according to a nonpartisan team of researchers based at Syracuse University that tracks immigration cases.

Asylum is never guaranteed and the need for it is hard to prove, something Chavez says many Americans don’t realize.

A young man from Haiti, who gives just his first name as Vilmy, explains that he’s been living in Tijuana for over a year while waiting for his turn to apply for asylum.

Vilmy leans in close, then asks, “Is there anything you can do to help us?”

His willingness to sacrifice so much — his homeland, his roots, his language — to start a new life in my country leaves me speechless.

As much as I might want to flee America when its bigotry feels like a curse, on this side of the border I’m the one who’s blessed — as much an example of this country’s wide-open sense of possibility as any white American.

Vilmy seems unaware that America’s immigration system historically has regarded Haitian refugees as undeserving of asylum. In the last year, border officials have turned away or deported hundreds of Haitians under the pretext of helping to slow the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S., despite knowing the refugees face danger from political turmoil back home in Haiti, according to an investigation by BuzzFeed News.

For its part, the Biden administration is slowly moving to reunite immigrant families separated under Trump. Vice President Kamala Harris has announced more than $300 million in aid to Central America to help stem the flow of migrants from that region. And after facing criticism over delays in lifting the Trump administration’s historically low cap on refugee admissions, Biden has quadrupled the yearly limit to 62,500.

Legal aid groups that have been given access to migrant facilities housing unaccompanied minors have reported disturbing conditions in recent months: Children confined to crowded tents are prevented from venturing outdoors for days at a time, or have to go days without showers. Many slept on gym mats with foil sheets. At one facility in Texas, lawyers found children as young as 1.

“Racism is real in America, and it always has been; xenophobia is real in America, and always has been.”

— Vice President Kamala Harris

Americans are deeply conflicted over Biden’s performance on immigration so far. An ABC News/Ipsos poll taken in late March found that 89% of Riis’ fellow Republicans and 54% of independents disapproved.

Even some Democrats are unhappy. Only 64% of them approved of Biden’s actions on immigration, a much smaller share than were pleased with his handling the COVID-19 vaccine rollout and the economic recovery.

“We were seduced into thinking that things were going to be radically different” with Trump gone, says Brandi T. Summers, a progressive scholar at UC Berkeley who studies how land can be used as a tool of both racial exclusion and social change.

L.A. has a long history of anti-Asian sentiment. In 1871, a mob attacked Chinese people, killing 19, including a 14-year-old boy and a physician.

Vice President Harris, during a visit to Atlanta with Biden after a gunman killed eight people, six of them of Asian descent, spoke of prejudice as embedded in America’s collective psyche.

“Racism is real in America, and it always has been; xenophobia is real in America, and always has been,” Harris said.

But Summers doesn’t believe that a more tolerant administration can, on its own, redeem a society that since its inception has wavered in its promise to treat people with humanity.

::

The U.S. and Mexico feel like extensions of each other in San Diego. When the sun goes down over the warships and sailboats of California’s second-largest city, the lights twinkle on the hillsides of Tijuana.

More than 90,000 Americans and Mexicans cross the busy portal at San Ysidro each day to go to school or work, to shop or to meet with friends and relatives.

“Our tías live on one side; our aunties live on the other side,” says Nora Vargas, the first Latina and first immigrant to serve on the San Diego County Board of Supervisors.

Generations of a family recall their memories of coming to California and the challenges they faced

Vargas, a 49-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen who was born in Tijuana, represents some of the neighborhoods that straddle the border.

For fronterizas like her who carry in them the cultures of both countries, the border isn’t necessarily something to dread.

On Hollister Street, the bright blue sky over the community garden makes the banana trees and collard greens stand out in vibrant green.

But immigration and the symbolism of the border are on some of the gardeners’ minds. Fay Benson, 65, says she immigrated from the Philippines to the U.S. as a little girl and understands how traumatic it can be to settle in a new country. She praises Americans as kindhearted but worries that it’s too dangerous to migrate to the border with children or to send them alone.

Sam Ramirez relaxes in the shade of avocado trees he grew from saplings. The 34-year-old travels regularly into the U.S. to visit his mother in San Diego and work in the garden.

His plot is an international affair, nourished with rich topsoil he cultivates across the border in Tijuana, where he lives. He kneels and scoops up some earth in his bare hands, then lets the soil of two nations fall through his fingers.

Ramirez sees selfishness and tribalism in the Trumpian view that migrants streaming toward the border represent a threat to America’s very survival.

“I feel like people are fearful of ‘the other’ coming in, because we all want to have our own thing protected,” he said.

Like the nutrients in his garden, he says, immigration can help replenish a society rather than deplete it.

Corruption underscores the challenge Harris confronts in working with leaders of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to stem migration to the U.S.

Living close to the border brings with it a moral obligation to look after those who need housing, food and help acclimating to the new culture after they cross over, says the Rev. Bill Jenkins, who runs Christ Ministry Center, an ecumenical nonprofit in a former Methodist church near downtown San Diego.

Over just a five-month period in 2016, the center temporarily housed about 5,000 Haitian migrants who crossed from Tijuana.

“We were literally a refugee camp right here in the heart of San Diego, and not many people knew about it,” says Jenkins, 72.

What’s sad, he says, is that “a lot of those who made it across were eventually sent back.”

With political tensions in the U.S. running high and racially motivated hate crimes on the rise, he wouldn’t allow reporters to visit any of the migrants living in his shelters for fear that publicity might make them targets.

As a white man who was profoundly shaken by the brutality of racism and Jim Crow segregation while growing up in Mississippi in the 1960s, Jenkins — who with his wife adopted a 5-year-old boy from Haiti — feels heartened by Biden’s view that we’re in a battle for the nation’s soul.

“It’s a battle for our soul in the political sense, and in the spiritual sense,” Jenkins says.

The country still has a long way to go before it can forge a singular identity that all Americans — including myself and other people of color who know its worst impulses — can embrace.

And yet, even with all of the nation’s flaws, Chavez, the immigration attorney, sees hope in this time of darkness and despair.

As San Diego’s response to the surge at the border shows, she says, “we are still a beacon of light.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.