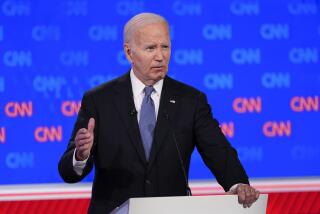

In his first 100 days, ‘Uncle Joe’ Biden combines progressive goals and a reassuring manner

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Throughout the 2020 campaign, pollsters in both parties said Joe Biden was well known, but not known well: Voters knew him as a former vice president and longtime senator but had only a rough sense of what he stood for.

As his presidency nears its 100th day, the blank spots are filling in. The resulting image is one most observers did not expect based on Biden’s largely centrist, four-decade record.

“A couple of months before the election ... did I think he would be a transformational president? I would have laughed at that idea,” said Democratic strategist Cornell Belcher.

“I would have been mistaken.”

Biden has governed in these opening months as a progressive — significantly to the left of his three Democratic predecessors on the issue of government’s role in society. With proposals such as expanded aid to families to cut child poverty nearly in half, a sharp cut in U.S. emissions of gases that warm the climate, and a major increase in spending on domestic programs, he’s gone well beyond what prior Democratic administrations backed.

“Government doing something for people ... that was an idea that was disabled,” said Princeton historian Sean Wilentz. “He’s trying to bring it back.”

Republicans have accused Biden of a bait-and-switch.

“He promised to work across the aisle — to work with Republicans in Congress. But so far, those words have been completely empty promises,” Rep. Mike Johnson of Louisiana, the vice chair of the Republican conference in the House, said on Wednesday, kicking off a series of GOP speeches criticizing the administration.

To their publicly expressed frustration, Republicans have had little success with that line of attack. They’ve gotten more traction by focusing on the administration’s troubled handling of an upswing of mostly young migrants trying to cross the southwestern border.

Biden’s activism amounts to a strategic bet that flips an idea that guided the last two Democratic presidents. Both Presidents Obama and Clinton were acutely aware of the risk of overreaching — alienating centrists by pushing plans seen as going too far. Biden has adopted the opposite view — that troubled times have made voters more open to activist government.

“I believe the American people are looking right now to their government for help,” Biden said in a White House speech a couple of weeks after the inauguration. “The way I see it, the biggest risk is not going too big … it’s if we go too small.”

That set the tone for key early decisions, especially Biden’s refusal to cut down his $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief package when a group of centrist Republicans offered a counterproposal roughly one-third as big.

That decision was not only substantively important, “it sent a signal” for future legislative battles, said Adam Green of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee.

Voters might not have expected so activist a program, but so far they like what they see: Roughly two-thirds of Americans, including about a third of Republicans, approve of the relief package, recent polls show.

The pandemic appears to have made many voters more supportive of government action, Democratic strategists say. Biden is a “Democrat who believes in the art of the possible, and what’s possible would have been a lot lower in normal times,” Green said.

But Biden also has an ability to put forward progressive ideas in a way that strikes centrist voters as nonthreatening, said Belcher.

“You cannot underestimate how comfortable Uncle Joe is for a lot of people. They give an old, white guy the benefit of the doubt,” he said.

Even as Biden has pushed activist policy, he’s succeeded in lowering the temperature of Washington’s political debates. That reduced partisan intensity has helped him, strategists in both parties say. But it could create a problem down the road, depriving Biden of the fervent support that can sustain a president in bad times.

“President Biden garners strong ratings, in part because he’s doing exactly what he said he would do when he ran,” said Democratic pollster Anna Greenberg: “Getting shots in arms, expanding COVID relief, improving the economy.”

“To some degree, he has let the work be his message. The only danger with that approach is that may not forge a deep tie with the voter that helps him through tougher times.”

The president’s identity, moreover, poses a challenge.

“Biden doesn’t personify the Democratic Party,” said Julia Azari, a political science professor at Marquette University in Milwaukee. “Older, white men — just by the numbers — are a very slim part of the Democratic coalition.”

Obama, as the first Black president, embodied change in a way that drew Democratic voters to him, Azari said. Biden has to cement their allegiance by what he can deliver.

He’s “made politics transactional again,” she said.

The president has carefully attended to that, publicly stressing the diversity of his appointments to federal offices and emphasizing racial and ethnic equity in COVID-19 vaccinations.

But his ability to deliver on major Democratic priorities beyond his spending plans remains a question mark. Biden has left unclear how much energy he’ll devote to measures on immigration, voting rights, gun regulation and changes in policing.

“What we’re all most interested in is the next 100 days,” said Frank Sharry, executive director of America’s Voice, a group that advocates for immigrant rights.

“They have to decide if they’re really going to fight” for legalization, Sharry said.

The House has passed two bills that together would legalize roughly 4.5 million of the estimated 11 million people living in the U.S. without authorization. Getting those, or any broader legalization measures, through the Senate would almost certainly require bypassing Senate rules that require most legislation to get 60 votes to pass.

“Will they spend political capital? I don’t know. I suspect they don’t know,” Sharry said.

Similarly, while Green praised Biden’s accomplishments, he pointedly added that the president’s proposals to counteract global warming fall far short of what he promised during his campaign.

So far, Biden has kept his options open, sticking to a few core topics — mainly the pandemic and economic recovery — with a discipline that contrasts with his longstanding image as garrulous and gaffe-prone.

“As you’ve all observed, successful presidents better than me have been successful in large part because they know how to time what they’re doing. Order it, decide and prioritize what needs to be done,” he said in a news conference in late March that provided a glimpse of how he sees the job.

First among those priorities has been the pandemic, the area on which he can claim his biggest success. More than half the adult population has gotten at least one vaccination shot, and the number of deaths dropped sharply, from a peak of roughly 3,500 a day in the week before his inauguration to an average of under 700 a day.

That achievement has helped reinvigorate the economy and rekindled a sense of optimism. The share of Americans who say the country is on the right track has risen to levels not seen in a decade.

That, in turn, has helped keep the Democratic Party united.

“Success begets success,” said Lanae Erickson of the centrist Democratic organization Third Way. Democrats of all ideological factions are “extremely motivated” to see Biden succeed because they know their own political survival hinges on his, she said.

Instead of Democratic infighting, it’s the opposition that remains divided.

“He’s governing in a very liberal way” but has “benefited from a big leadership vacuum in the Republican Party,” Republican strategist Alex Conant said of Biden. “We’re seeing Republicans spending a lot of time attacking each other, not the administration.”

With the successful vaccination campaign and the passage of his relief package, Biden has succeeded at changing voter expectations shaped by a decade of political gridlock in Washington, said Democratic strategist Joe Trippi.

After the chaotic clamor of Donald Trump’s presidency, Biden faced a situation similar to the one Jerry Brown confronted when he followed Arnold Schwarzenegger into California’s governor’s office, said Trippi, who worked as a senior advisor to Brown’s 2010 campaign.

Voters started with fairly low expectations in both cases — they simply wanted a basic level of competence and experience. Brown used to say of Californians in 2010, “They wanted someone who would turn down the temperature and know how to turn the lights on” in the Statehouse, Trippi recalled. Similarly, in 2020, many voters would have been happy with any president who wasn’t Trump.

Brown quickly exceeded that threshold expectation, and Biden has done the same, Trippi said: “On the two things that matter the most to voters right now — the vaccine and getting the economy moving — he’s been effective.”

Biden’s supporters say that image of competence is a key attribute in voters’ eyes.

“Competency is his strongest selling point,” said Steve Schale, who runs the main pro-Biden super PAC, Unite the Country.

About 50 days into Biden’s tenure, the group polled roughly 5,000 voters in 10 swing states. Voters “appreciated the fact that he was head-down, doing the work,” Schale said.

That’s one big reason the continued problems at the border pose a problem for Biden. Not only do the images of teenagers crowded into Border Patrol lockups revive public concerns about illegal immigration — an issue on which Republicans have traditionally held an edge — but the chaotic scenes have the potential to undermine the administration’s goal of low-drama, steady execution.

The border problem is also a reminder of how easily external events can derail a president’s agenda.

The big question voters ask is, “Did you get anything done?” Trippi said. A president has only limited time to answer that question.

Biden “knows more than anybody who has been there in a while how little time he’s got.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.