Lifting kids out of poverty could be Biden’s legacy, but cost raises doubts

- Share via

WASHINGTON — As Vice President Kamala Harris toured a child-development center in West Haven, Conn., recently, she singled out a newly adopted program that has long been a goal of the area’s member of Congress, Rep. Rosa DeLauro, chair of the House Appropriations Committee.

A major increase in benefits to families with children, included in the COVID-19 relief bill that President Biden signed into law last month, will cut child poverty nearly in half this year, according to outside experts.

“This was the intentional purpose of the American Rescue Plan,” Harris said, “to look at our children, to bring them out of poverty, and to do what has long been overlooked, which is to understand that, you know, our children — we cannot, in public policy, subordinate them.”

That claim comes with a catch, though: The relief law created the new benefit for just one year. And so, before Harris left in her motorcade, DeLauro (D-Conn.) grabbed a private moment to deliver a message.

“I said, ‘I can’t let you leave before saying we need to make this permanent,’” she recounted.

Harris couldn’t give a firm commitment, however. The benefit’s recent history underscores why.

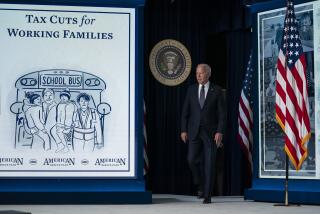

The expanded child benefit and its potential to reduce poverty has become one of the administration’s proudest boasts — a potential legacy achievement for Biden. First Lady Jill Biden talked of it Friday in Alabama. The president has mentioned the accomplishment repeatedly.

Yet its future remains uncertain given its cost: projected at more than $100 billion for this year. The proposal to make that cost a permanent part of the federal budget sits at the crossing where the administration’s transformative ambitions have begun to run into the limits of how much it can spend.

The new law would provide almost all American families $3,000 for each child up to age 18 and $3,600 for children under 5 this year — a near-universal child allowance. It boosted the amount, which had been $2,000, and made the money available to low-income families previously excluded.

As the encounter between DeLauro and Harris showed, a friendly, but intense, lobbying campaign aimed at the White House now centers on how much money to devote to alleviating child poverty over the next decade.

The concept of the child allowance is appealingly simple: To lift children out of poverty, don’t create a big, new federal program; give parents money.

A study by the National Academies of Sciences found in 2019 that a benefit like the one now in place would cut child poverty nearly in half, raising some 10 million children above the poverty line. It was by far the most effective of several options the study examined.

But cost has repeatedly stymied the effort. DeLauro first proposed the idea in 2003. Hillary Clinton declined to endorse it in her 2016 presidential campaign, largely because of the cost. And while Biden as a candidate endorsed it in September, his transition team left the plan out of early drafts of the COVID-19 relief bill, setting off intensive lobbying from Democratic backers over a key weekend in early January.

His decision about extending the program is expected soon, as early as this week, as part of his American Families Plan, the third and final piece of the long-term increase in federal spending that the administration is requesting to “build back better,” as Biden’s slogan goes.

Late last month, administration officials floated the possibility of a five-year extension, which would lock the expanded assistance into place for the rest of Biden’s term but leave its eventual fate to a future Congress.

That would free space in Biden’s plan for other proposals — perhaps a down payment on his public option on healthcare. And by the time expiration rolls around, some officials figure, the program probably will be so popular that lawmakers would simply extend it again.

Backers, however, argue that a five-year extension puts too many children at risk of a shift in the political winds. Just as Social Security benefits for retirees aren’t subject to periodic votes over renewal, neither should benefits for children, they say.

“We don’t have to accept one of the highest child poverty rates in the industrialized world,” Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) said in an interview. Bennet has been among the lead Senate champions of the plan, along with Democratic Sens. Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Cory Booker of New Jersey.

“I’m going to continue to push for permanence,” he said.

Asked Monday, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki declined to say when Biden would unveil the American Families Plan, or whether he’d propose making it permanent.

The president believes there are huge benefits to the child tax credit, Psaki said. “He feels it’s important, it’s vital.”

For many low-income families, the benefit will represent a major boost. A single mother with two children working for $15 per hour would see a 25% increase in her income. Administration officials hope to be able to provide the money in monthly increments, starting this summer, rather than requiring families to wait for a lump-sum rebate in the spring.

The program builds on the child credit that has existed in the federal tax code for decades. Ironically, given its current prominence on the Democratic agenda, the tax credit grew out of the Contract for America pushed in 1994 by Newt Gingrich, the conservative Republican from Georgia who subsequently became House speaker.

Gingrich backed the credit as a form of tax relief for middle-class families, especially for those with large numbers of children. But starting in the early 2000s, Democrats, with backing from some Republicans, argued for expanding it and making the benefit available to low-income households as well by making it refundable, meaning that those who don’t earn enough to take full advantage of a credit would get a refund.

In recent years, backers of the credit used recurring debates over expiring tax breaks as opportunities to cement the child credit into place as Democrats’ top priority.

In 2014, for example, Brown pushed the Obama administration to insist on expanding the child credit as the tradeoff for agreeing to Republican demands to renew business tax breaks.

“The idea was to make it a mainstream Democratic issue,” Brown said. Within the party caucus, support “just built and built,” he said, until it became a consensus position.

By last year, every Senate Democrat except Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema had signed on as a co-sponsor of Bennet and Brown’s bill.

Yet the issue received little public attention. Unlike many efforts at social legislation, expanding the child tax credit has never been the subject of a big, public campaign.

“It’s a change in the tax code,” Bennet said. “People have had a hard time understanding the order of magnitude” of what it could do.

While Biden as a candidate said little about child poverty, his economic and political advisors were familiar with the tax credit. During the fall, backers of the expansion plan pressed the case with them.

Brown talked the plan up with Ted Kaufman, Biden’s onetime chief of staff, who succeeded him in the Senate when he became vice president and headed the Biden transition team. DeLauro spoke with former Sen. Christopher J. Dodd of Connecticut, her onetime boss who is a close Biden friend. Bennet has ties to several key Biden aides, including domestic policy advisor Susan Rice.

Nonetheless, Biden’s transition team left the benefit out of initial drafts of his COVID-19 package, which reached Capitol Hill at the end of the week that included both the Georgia Senate elections and the insurrection at the Capitol.

White House officials have declined to say why it wasn’t included. Democrats close to the process said some Biden aides feared the relief bill was getting too large and wanted to defer the costly child benefit until a later bill. But in the aftermath of the Georgia victories, which gave their party control of the Senate, congressional Democrats were in no mood to temporize.

DeLauro recalled that over the previous year, “I was told all the time that ‘We don’t have the Senate, and we don’t have the White House, so we can’t get it done.’”

“I understand reality,” she said, “if you can’t get it done, you can’t get it done.” But once the Democrats had won full control of Congress, “I’ve got to say, ‘Whoa, what’s going on here? It’s time to move, now.’”

“I said some other things I won’t repeat in print,” she added.

“That weekend gave us the opportunity to make the case,” Bennet said: “If not now, when?”

Ultimately, Biden aides expanded the size of the relief package, swelling it to its eventual $1.9-trillion scope and making room for the child benefit, as well as other Democratic priorities.

“From Friday to Tuesday, we went from nothing to the whole thing,” said one top Democratic aide involved in the discussions, who was not authorized to comment by name.

Just two months later, as the Senate passed the relief package, with the child benefit included, Brown told colleagues that in his 28 years as a lawmaker, “there’s nothing Congress has done that’s this big, that will have this much impact on this many people.”

The issue now is, for how long?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.