Column: The tragedy of Dianne Feinstein

- Share via

If Dianne Feinstein hadn’t lived the life she had, her story might be the product of a screenwriter’s over-fertile imagination.

The synopsis: After surviving an abusive childhood, Feinstein overcomes personal loss — she is widowed at age 45 — and repeated electoral defeat to become a pioneer for women in politics and powerful member of the U.S. Senate. Along the way she survives a mayoral recall effort, a brutal Senate reelection campaign, an attempted bombing of her home and a gruesome brush with death.

The opening scene: November 1978, San Francisco’s Beaux-Arts City Hall, where former Supervisor Dan White has just shot and killed Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. Feinstein, who chairs the Board of Supervisors, rushes to Milk’s aid. She reaches for a pulse and plunges her finger in a bullet hole.

The closing scene: Deep into her ninth decade, Feinstein is no longer the politically revered figure she once was. There is talk of mental decline, of selfishly overstaying her time in office and calls for the Democrat to resign from the Senate for the good of her state and the country.

The slow, sad fade is not simply a function of Feinstein’s age — she is 87 — but also the fact that times and the political world have changed and Feinstein, whether unwilling or unable, has failed to change along with them.

“She’s not performative and she’s not ideological, and those are the two things that matter now in Washington,” said Jerry Roberts, a veteran political reporter and Feinstein biographer, who first covered her in the early 1970s. Worthy or not, “her time has, in fact, passed because of the way politics have become weaponized, the way the Senate has been transformed, the way social media defines people now.”

A recent poll by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies showed a mere 35% of Californians approve of the job Feinstein is doing, marking the first time in her nearly three-decade Senate career that a plurality of those surveyed hold a negative view. The steepest decline was within Feinstein’s own Democratic Party.

A new Berkeley IGS poll found a plurality of Californians have a negative view of Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s job performance for the first time in her Senate tenure.

Disgruntlement on the left is nothing new. In the wacky world of San Francisco politics, Feinstein has long been seen as a prude and a scold and a tool of corporate interests. Statewide, many progressives consider her too centrist and overly accommodating of Republicans, even though her voting record has been anything but conservative. Feinstein’s political strength has always been with voters hewing closer to the middle, but even that support has eroded amid reports of her cognitive decline.

Someone who attended regular meetings with the senator over the course of many years described an obvious, if not persistent, change in her behavior.

“Starting under [President] Obama, I began to notice she seemed confused in meetings,” said the former government affairs executive, who did not want to be identified to avoid causing trouble for the large firm that employed him. “But it was inconsistent. Sometimes she was clear and coherent in meetings. Other occasions, she didn’t seem to understand the issues and sometimes even the person with whom she was meeting.”

Feinstein defended herself in a December interview with L.A. Times columnist George Skelton.

“I don’t feel my cognitive abilities have diminished,” she said. “Do I forget something sometimes? Quite possibly.”

But, Feinstein went on, “I have an effective staff… We do get things done and we do pass bills. You do get older, that’s true. But I have been productive.”

In fact, the day the UC Berkeley poll circulated and sparked a new round of Feinstein-should-go agita, the senator’s office said the Coast Guard was adopting a sweeping series of reforms designed to make small passenger vessels safer. The changes were a result of the work Feinstein and other California lawmakers have done since a 2019 Labor Day fire on a dive boat off the Channel Islands killed 34 people and exposed serious flaws in boat safety.

It was something concrete and typical of Feinstein’s approach to the Senate in recent years, shunning high-profile political fights in favor of lesser noted, more practical achievements. That said, legislative accomplishment — especially on an issue like small-boat safety — isn’t the sort of thing that excites partisans, or lights up the political food-fight shows on cable television.

Republicans once more than held their own at the municipal level in a deep-blue state. No longer.

Feinstein’s age, it is worth noting, was an issue when she ran for her fifth full Senate term in 2018. She was reelected, handily.

Then, last October, Feinstein hugged Sen. Lindsey Graham and praised the South Carolina Republican for his handling of the Judiciary Committee hearings for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett. The reaction among Democrats was scalding, the embrace seen as proof of Feinstein’s senility, or selling out to the GOP, or both. (She subsequently voted against Barrett’s confirmation and spoke in opposition on the Senate floor.)

Whatever the motivation, Feinstein’s action showed, at the least, an acute political tone deafness. Facing pressure from the left, she chose not to pursue the chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee after Democrats took control of the Senate, or — despite her seniority — the leadership of any other committee.

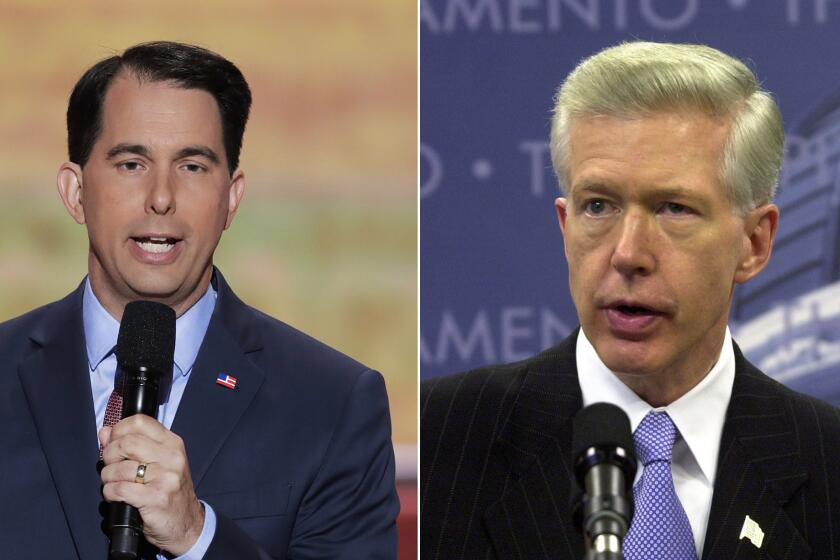

Democratic pollster Paul Maslin fought efforts to recall Gray Davis in California and worked to oust Scott Walker in Wisconsin

Bipartisanship, which is to say working with people with whom you may have deep and stark disagreements, is widely disdained these days as a form of retreat and surrender. It is, however, at the core of what Feinstein has always been: a believer in deliberation and political decorum, in practicality and legislative pragmatism. “Compromise,” she has said to the derision of fellow Democrats, “is not a bad word.”

Today, Feinstein is a subject of scorn, considered by many a relic who is well past her prime, who refuses to yield to someone younger, more vibrant, more politically pugnacious and more reflective of California’s kaleidoscopic racial and ethnic diversity.

History, with its long view, is likely to be much kinder.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.